Next story: Seven Days: The More Calories, Less Filling News of the Week

Hope and History

by Bruce Fisher

Austerity, priorities, and a new economy

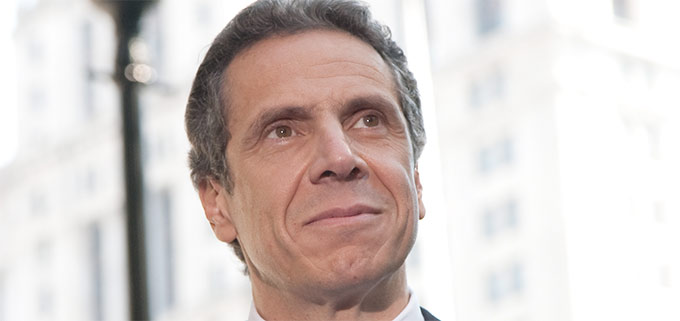

As the new year dawned, Andrew Cuomo took the oath of office as governor of a state with a $10 billion budget gap, a divided state legislature, dysfunctional economic development agencies and authorities that never coordinate their actions, and now, it seems, he must also deal with New York State’s own Erin Brockovich problem. The federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Christmas gift to Buffalo, Syracuse, New York City, and 28 other cities was its acknowledgment of a scientific watchdog’s December report that all these cities have cancer-causing chromium-6 in their water.

Chromium-6 is a proven carcinogen. The actress Julia Roberts portrayed Erin Brockovich in the eponymous film about how Chromium-6 pollution was causing widespread sickness in a small community. Until the real Brockovich won a $300 million court settlement, the big corporation that caused the problem did nothing to clean up the pollution, but spent millions on cover-up, denials, PR, and demonizing its critics.

How exactly does one do economic development if a community’s water is polluted with cancer-causing contaminants? A news blackout helps: Since the holiday news flash about chromium-6, there has been no further news coverage of the problem in Buffalo.

Turning a blind eye is established practice here. In December, state economic development agencies ignored the original purpose of the New York State Power Authority funds, funds which were obtained specifically for environmental remediation, in favor of endorsing Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation’s plan to build short, shallow replicas of old canals in the Canal District, leaving the adjacent Buffalo River full of sewage and contaminants. According to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the Buffalo River’s water is so contaminated that 34 percent of the black bass and 87 percent of the brown bullheads that live in it have tumors, facts that have been reported only in Artvoice.

One hopes that Governor Cuomo will appoint an environmental leader like former Commissioner Pete Grannis, whom former Governor David Paterson dismissed allegedly for complaining about the loss of professional staff whose job it is to enforce pollution regulations and direct cleanup funds to our own Erin Brockovich problems. But whoever heads the Department of Environmental Conservation will need the staff, and staff cost money. Money for state operations comes from taxes, which means that we, and our new governor, must urgently focus on how to get the state’s economy strong enough to meet our challenges.

Cutbacks versus investment

A December 2010 report from the Kauffman Foundation for Entrepreneurship has a lot to say about how state governments should deal with the new reality of revenue shortages. State governments have far less power than national governments in shaping economies, but governors are on the firing line to produce economic turnarounds, and they have lots of policy tools at hand. No governor, except perhaps Governor-redux Jerry Brown of California, has a bigger job ahead than Andrew Cuomo.

States do matter. The leaders of California have long cited how much larger their state’s economy is than those of various sovereign countries; with a current Bureau of Economic Analysis figure of $1.09 trillion, New York’s 19 million people have a larger gross domestic product than every other state except California ($1.89 trillion) and Texas ($1.14 trillion), which even individually are bigger than most other national economies on the planet. Economic contraction over the past few years has been a reality.

One wishes that the Kauffman report had been organized by metros rather than by states. Andrew Cuomo’s problem is not the dynamic, growing economy of the greater New York City metro area, which contains about 14 million of our state’s 19-plus million people, and which produces so much excess tax revenue that not only does Upstate feed off it, but so does the rest of America. No, the Downstate portion of Cuomo’s New York is burgeoning. It’s the economy for the five million folks of Upstate New York that is the challenge.

The Kauffman report addresses this problem with an intriguing international example from recent history. The nation of Finland, population about 5.3 million, went into an economic tailspin after the Soviet Union fell apart in 1990. But rather than take the “everything should be on the table” approach to cutting its budget during its time of fiscal crisis, Finland “took the long view,” says Kauffman: “They cut government spending, but they increased investments to help transform the Finnish economy from one dependent on natural resources to one dependent on knowledge and innovation.”

The biggest target of Finnish investment was primary and secondary education. Finland is a small country. Its GDP is only $190 billion, according to the OECD, and their per-capita product $35,918, compared to $50,205 in New York State as a whole. (I don’t know how to calculate the GDP of Upstate New York, other than by aggregating the metros, but I will report back soon.) The history lesson is this: Finland’s GDP and its citizens’ per-capita income were half that before the Finns fixed their schools.

Kauffman now calls Finland a model of what an innovation-driven economy should look like. Everybody who looks at it concludes the same thing: It was fixing the schools that did it. In the latest international comparisons, the Finns tied South Korea for first place among all 70 OECD countries in results from a two-hour test administered to hundreds of thousands of kids worldwide. The test measured literacy, math, and science knowledge among 15-year-olds. Chinese kids in Shanghai scored best on math, US kids beat most on science, but we scored lower because we in America have a huge problem holding us back: The OECD found, as has Syracuse University’s Jerry Grant, that when kids are segregated by income, the poor kids fail and bring everybody’s numbers down.

Note to US governors: The evidence says you should make like Finland, invest in the right stuff, desegregate your schools by income, and stick it out for the long term.

Bold strokes or baloney?

Andrew Cuomo and his staff know, with great specificity, just how much it costs to keep the dysfunctional, locally administered school apparatus of New York State going. His budget challenge is not only a current-accounts problem but a structural one: Albany is not the only state capitol that shovels money into local governments and school districts in an old political arrangement that keeps the local government natives quiet. But before he and other governors go after local school districts—of which there are 62 city districts and more than 600 suburban and rural districts, by the latest count of the New York State Education Department—the governors need a political target. They have all chosen to go after the pay and benefits of public employees, including teachers.

But when that skirmish is finished, the governors then have to get serious. They’re going to have to take on the dysfunctional, duplicative, monstrously inefficient target called separate school districts. The international evidence has poured in, and even in Buffalo, the general media find themselves able to report that the economy is better when reading, science, and math scores grow. But there the story stops: Social scientists know that scores stay low when poor kids are isolated. We have known this since the 1960s. The OECD knows it. Our nearby peer city of Hamilton, Ontario, having been apprised only a year ago of the new evidence in Professor Grant’s book—which shows how educational outcomes are better in income-mixed, county-administered Raleigh schools than in income-segregated, city-only Syracuse schools—is moving aggressively to end their old segregation-by-income, city-only system. Will Cuomo’s education bureaucracy move on this, and give New York State regional schools? The evidence is in that economies grow when that happens—but will anybody in Albany be bold enough to do what Finland and Raleigh did, and what Hamilton is doing now?

There is obviously more to innovation economies than schools, of course. New products, processes, and commercialize-able intellectual property come from people with higher education, and in this realm, Andrew Cuomo would seem to have a distinct advantage. The number of degrees our New York institutions hand out is impressive. According to the December 2010 report from the National Science Foundation on how many PhDs were earned in 2009, New York State institutions conferred 3,852—second only to California’s 5,966. Albany Medical College conferred nine, Alfred one, Clarkson 22, Cornell 515, Renssalaer 131, RIT 10, Upstate SUNY campuses 287 plus UB’s 312, Syracuse 136, Rochester 220—the brain-numbing numbers mean that there are almost 4,000 people, just in this past year, including more than 500 from west of the Genesee River, who have certificates that say they’ve achieved the highest academic credentials available.

But is that enough? Is it relevant? More relevant, says some recent thinking, are the number of generally educated folks, i.e., those with bachelor’s degrees. More relevant still, according to the paradoxical utterances of a conservative economic theorist, are the messages we send.

Not poor enough?

In New York, there are agencies—the Thruway Authority, the New York Power Authority, the Empire State Development Corporation, and many others—that spend tens of millions of dollars of public funds on projects that do great things for insiders and not much measurable good for anybody else. The aroma of corruption is a problem, but so is sheer the irrelevance of the spending. Questions that poor countries would ask are not asked here, such as these: How will the decision to spend $153 million of public funds on real-estate-development-related projects in Erie Canal Harbor increase the sustainability of Upstate’s largest metro region? How will the Thruway Authority’s decision to move the tolls eastward from Transit Road, at a cost of tens of millions of dollars, effect the behavior of drivers in the Buffalo metro area, which is already losing population even as real-estate development sprawls farther and farther outward? Why, in a state with both a state and a federal mandate to use renewable energy, even as crude oil prices once again reach far past $100 a barrel and gasoline prices jump over $3 a gallon, is there no metro-by-metro Upstate plan to rein in fossil-fuel use in favor of renewable energy for transportation?

The answer seems to be this: Upstate is on the Downstate dole, but the empowered voices in Upstate keep asking for the same short-term, insider-directed projects that they’ve always asked for, and to shut us up, Albany throws some New York City money our way to squander as Upstate always has.

Our river’s water is dirty, but because nobody empowered is asking for clean water, the public money gets misspent on commercial space. Our resident population obtains BAs, MAs and even PhDs from area universities—more than 300 from UB alone in 2009—but our retention of these assets is inadequate to move Upstate into the ranks of places like Finland, where the innovation economy is sufficiently strong enough to keep the talented from leaking out to enrich the rest of the world.

As long as our empowered Upstate voices keep asking for the wrong stuff while the core challenges remain unaddressed, we can expect the same result. We will have successful higher-educational institutions that graduate accomplished young people, next to expensive public schools that treat the middle- and upper-middle classes beautifully but that leave poor kids festering in bad culture and worse rhetoric, with racial ranting on all sides. We will have dirty water that makes national news. We will have the opposite of what the economists call the “agglomeration effect,” which is the upward tornado of economic activity that happens when folks do what they do close to one another, rather than sprawled out all over distant suburbia. Andrew Cuomo can’t be expected to task his staff to work on all these issues today. He should at least, however, expect that his agencies start acting as if they are too poor to spend money that our tax base is too small to keep giving them. But as long as Downstate continues to subsidize Upstate, evidently we’ll never be poor enough to get serious about fixing our fundamentals.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n1 (week of Thursday, January 6) > Hope and History This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue