The Moderns

by Jack Foran

In-Depth at the Albright-Knox examines Picasso, Braque, Leger, Delaunay

The In-Depth exhibit currently at the Albright-Knox is a short course—and not even all that short—on the history of early 20th-century art. The exhibit consists of all the Albright-Knox collection of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Sonia Delaunay.

Picasso is the centerpiece, of course, represented by an amazing 71 works. For each of the other artists, there are about two dozen or so.

The Picasso installation starts off with some early etchings, a drawing that looks like notebook sketches, and an uncharacteristically convivial family-at-supper scene from his characteristically somber and sorrowful Blue Period.

The Blue Period was followed by the cheerier Rose Period’s focus on circus performers and harlequins and Picasso’s meeting and collaboration with Georges Braque to found cubism, the single most significant innovation in the whole story of modern art.

Picasso’s startling creation of cubism was marked by the famous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907. The Albright-Knox has La Toilette from 1906. In it you can see the movement toward flatness of the depicted figures that would become a main motive of cubism—cubism would break up the figure into facets in a way that led directly to abstract art but was also a radical coming to terms with the flat surface of the canvas that Manet, Degas, and Cezanne had laid the groundwork for—as well as manneristic elongation of the figures, indicative of a dissatisfaction with traditional, one might say classical, representation, that is, figures in art looking pretty much the way they look in life.

Explanatory text on the wall next to La Toilette relates that because of the blatant nudity of the picture, early benefactor A. Conger Goodyear was kicked off the Albright board after he acquired it for the gallery in 1927.

Another not-so-blatant nude—the nudity being obscured by the cubist technique—from 1909-10 is the epitome of first-stage or so-called analytical cubism. Second-stage or synthetic cubism, which often involves collage or related compositional techniques, and is in general more decorative and less cerebral than analytical cubism, is represented by such works as a still life with a vase, fruit, and a glass from 1937.

A sculptural head of a woman is less successful cubism in that much of the idea of cubism—in breaking the image into facets, presenting the different moments of the viewer’s viewing of the object, and thus different aspects—is the incorporation of three-dimensional sculptural effects in painting, the two-dimensional medium. In sculpture, cubism loses some of its purpose and its punch. Cubism in sculpture is more referential than essential.

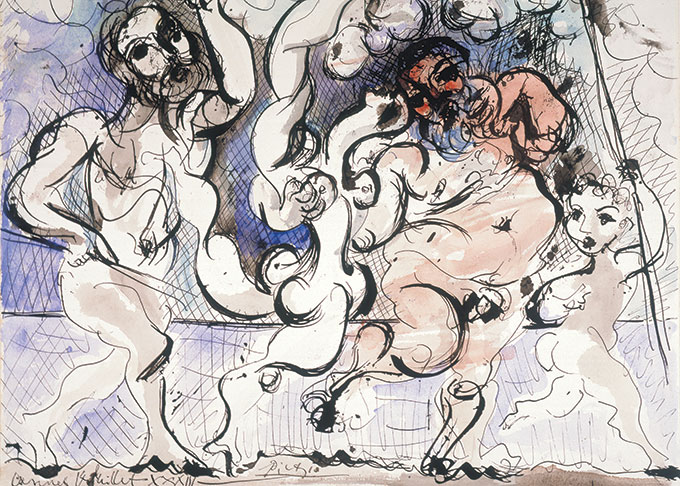

Picasso’s long stretch of middle years—roughly the 1920s through the 1950s—were a somewhat idyllic period, before he began to be haunted by considerations of looming mortality, which for Picasso were also considerations of immortality, his place and rank among predecessor titans of art such as Velazquez and Ingres.

Representative works from the middle years include Femme au bord de la mer, a lithograph from 1949, and an untitled drawing of a head—it could be a portrait of Apollo—in a few convincing, compelling gestures, from 1950. Both works have a Classical Greek reference—serenity, self-assurance, perfection.

And from roughly the same period, a series of over two dozen illustrations for a deluxe edition of Buffon’s l’Histoire naturelle in a variety of representational styles. From playfully painterly frogs on lily pads, to more scientifically sketch-like birds constructing a nest, to a dimly visible lobster underwater amid seaweed, to a comical cartoon rooster, to crickets with bejeweled carapace.

A 1964 painting from his artist and model series represents an ultimate effort (and you might say success) in the lifelong project or obsession to wrest three-dimensionality onto the two-dimensional painterly plane. You see the model simultaneously from the front and from the rear. While the artist stares straight out of the picture, maybe a little in awe of what he has just accomplished. The depiction of the artist is also one of the first of the series of increasingly mortality-haunted self-portraits he would produce (à la Rembrandt) in his final years: A photo on display shows Picasso in his studio about this time amid a number of his paintings including this one.

Nearby is his comic sculptural treatment of the two- versus three-dimensionality matter in the Baigneuse jouante (Picasso jouant?), wherein the bather’s breasts and buttocks (notably three-dimensional features of female anatomy) are rendered in sheet metal (a notably two-dimensional material). It’s cubism backwards. Sculpture according to the rules and conditions of painting.

Among late works are three stages of a David and Bathsheba lithograph—a kind of surrogate of the artist and model theme, expounding the voyeuristic erotic implications—proceeding from sketch-like initial stage to embellished middle stage to final stage abstraction.

Braque met Picasso in 1907 and they collaborated on cubism until 1914, when Braque went off to war. When he returned from the war, he went off in a somewhat different direction from Picasso, but also in many ways parallel. Artworks by Braque in the exhibit include several synthetic cubist paintings from the 1920s, some later freehand drawings evoking the idea of form as shape-shifting, and a stark late work bird etching in contrasting monotones of black, white, and two or three shades of gray.

Léger is the romantic poet (as painter) of the machine age. He seizes on inert industrial forms and invests them with soul. The enterprise is tendentious but expansive. He teaches a vitalism that informs industrial apparatus and processes as if in a valiant attempt to stave off their conspicuous dehumanizing potential. A small Léger sculpture in plaster is emblematic, called The Walking Flower. The colorful flower is endowed with an ambulatory capacity, as Léger conceives some ultimately humanistic animating quality in industrial machinery.

Léger’s art could be called geometric abstraction. Sonia Delaunay does geometric abstraction about just the artistic palette and Euclidean forms. And she was a poet literally, as well as a painter (as well as a costume designer, fabric designer, set designer, etc.). Several of her works on display are coloristic abstraction illustrations of poems by various poets and a poem of her own that describes her sense of rapport between poetry and painting. It begins, “Poésie de mots/ poésie de couleurs…”

These artists were fairly exact contemporaries. All were born within the years 1881 to 1885 and all died fairly old: Léger in 1955, Braque in 1963, Picasso in 1973, and Sonia Delaunay in 1979. Her artist husband, Robert Delaunay, died young, in 1941.

This is the first of a planned series of In-Depth exhibits at the Albright-Knox based on works from the collection. The current exhibit continues through June 5.

—jack foran

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n13 (Week of Thursday, March 31) > The Moderns This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue