Next story: Calling a Time-Out on Buffalo Public Schools

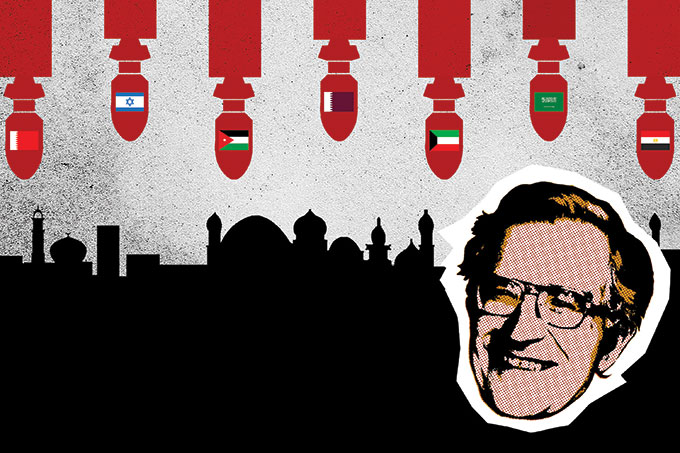

American Bombs: an Interview with Noam Chomsky

by Geoff Kelly

Noam Chomsky, who comes to Buffalo on May 12 to benefit the WNY Peace Center, talks about US policy failures in the Middle East

Noam Chomsky will deliver a lecture in Buffalo next Thursday, May 12, at Canisius College’s Montante Center. The talk is a benefit for the Western New York Peace Center, whose members invited Chomsky to come, and tickets ($15 for members, $25 for nonmembers) are available only through www.wnypeace.org.

Move fast, because the talk is close to sold out. Chomsky’s visit is co-sponsored by the Canisius College Peace & Justice Studies Program and the college’s Amnesty International chapter. Doors open at 6:30pm and the lecture begins at 7pm.

Chomsky is one of the 20th century’s most accomplished and rigorous intellectuals. He began to make his name as a linguist and philosopher in the 1950s, and later, during the Vietnam War, as a political dissident, the role for which he continues to be best known. He has written or co-written more than 150 books; about a third of these have to do with linguistics, the rest with political criticism and the exercise of power, particularly as demonstrated in US foreign policy.

Next week’s lecture here will focus on the policy of the US and its allies in the Middle East, a subject about which Chomsky has been writing since the early 1970s. In a recent essay called “Is the World Too Big to Fail?” Chomsky coined a new phrase to describe the cultivation of dictatorships in the region while ignoring or repressing the wills and voices of local populations. He names the doctrine—which holds that everything is fine so long as no one can be heard to complain—for Carnegie Endowment Middle East specialist Marwan Muasher, who may not be flattered by Chomsky’s attention.

Chomsky took a few minutes last week to talk to AV about Muasher and the Middle East.

AV: Can you describe what you’ve been calling the Muasher doctrine?

Chomsky: What’s been going on in the Middle East, basically—and they don’t want to admit it—is the US and its allies have been supporting really harsh, brutal dictatorships for a very long time. And they’ve known for years, it’s not been a secret, that the population is strongly opposed to US policy. This guy Muasher, he’s a former Jordanian high official, which is a dictatorship of course, and he’s now the Middle East specialist for the Carnegie Endowment, and he was describing the principle that as long as people are quiet and subdued, we don’t really care what they think. Everything is fine.

It works in the United States, too. As long as people don’t make too much of a fuss, we’ll get away with whatever we can. In the Middle East it’s been going on for decades, in fact all over the world. But what’s striking right now is people aren’t quiet, and therefore the US and its allies and Israel are pretty upset, because you can’t count on your favorite dictator to keep everything under control. And of course, since Washington and everyone else is terrified of democracy, they have to find some way to keep the thing under control even if their favorite dictator isn’t there.

Incidentally, this happens over and over. People act as if it’s something new but it’s as old as the hills. You just look through the record: Somoza, Marcos in the Philippines, Duvalier in Haiti, Mobuto in the Congo, Suharto in Indonesia. You support your favorite dictator as long as you can, and if it becomes impossible to continue to support him—like maybe the army moves against him, and you can’t do it anymore—well then, what you have to do is shelve him somehow, put him out to pasture, and pretend that you’ve always been a passionate supporter of the people and of democracy, and then try to reinstall the old regime. Try to make sure that the basic system remains, even with a change of names. And that’s done all the time. There’s nothing new in this.

AV: Why do you suppose Arab governments have been susceptible to popular uprisings this year as opposed to any other year?

Chomsky: Well, first of all they’re not. The tough dictatorships are staying, like Saudi Arabia, which is the most important country and is one of the harshest and most reactionary anywhere. And it’s a very close ally of the US; of course, they have all the oil. I mean, there was an effort at a protest in Saudi Arabia—you know, one of these Friday protests that are going around—but the security presence was so extreme and intimidating that people were afraid even to come out into the streets. The same in Kuwait. And in Bahrain, where they weren’t able to crush it all at once, there was a Sunni-led invasion, and now it’s brutally crushed.

AV: And Bahrain doesn’t have oil anymore, just the naval base.

Chomsky: That is the base for the US Fifth Fleet, but it’s more than that. Bahrain is mostly Shi’ite, and it’s right across the causeway from eastern Saudi Arabia. Eastern Saudi Arabia is also mostly Shi’ite, and that’s where all the oil is. And the concern is—it’s a deep concern for a long time—that there would be an independent Shi’ite movement which would control most of the world’s oil, because by accident of history and geography the world’s major oil supplies are concentrated in mostly Shi’ite areas: eastern Saudi Arabia, southern Iraq, and southwestern Iran. And there’s always been concern that they could get together and pull out. For the Saudis and for the US, Bahrain is extremely significant for that reason. That’s why they wouldn’t let it get out of hand.

So it’s not quite true that the governments fell. I mean, some of them did. In Tunisia and Egypt, the popular uprising did throw out the dictatorship. They tried to repress it and it didn’t work. In Egypt and Tunisia, the army just didn’t go along with it, so then the dictator’s stuck. That’s happened elsewhere, like the Philippines, Indonesia, a lot of places.

Now the problem is to try to control it, to make sure there’s no major change.

AV: You ended a recent essay on this pessimistic note: “All of this, and much more, can proceed as long as the Muasher doctrine prevails. As long as the general population is passive, apathetic, diverted to consumerism or hatred of the vulnerable, then the powerful can do as they please, and those who survive will be left to contemplate the outcome.”

Chomsky: Well, that wasn’t intended…maybe it came across as pessimistic, but what I was really trying to say is “Look, we don’t have to accept that doctrine. People in Egypt didn’t accept it, why should we?”

AV: What lessons can dissenters here take from the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia?

Chomsky: The uprisings in Egypt, for instance, they were taking place and still are taking place against a brutal, repressive, murderous state. We’re pretty free. We’re not going to face torture chambers or thugs being sent out to smash up people. To a limited extent, yeah, but nothing like in Egypt. I mean, if they can do it there, we can far more easily do it here. That’s the lesson. And it’s part of our own history. That’s how we got to be a more free country. It wasn’t given as a gift.

AV: Do you feel like your political work furthers some slow, inevitable progress toward a better, more just world, or are you and others like you always just fighting off the darkness?

Chomsky: It’s a combination of both. Depends what the circumstances are. I mean, right now we happen to be in a period of deep reaction, so there’s a defensive action. There’s a striking similarity between Egypt and the United States. There the trajectory is moving forward. They’re fighting for rights they’ve never had. You go to Madison, the trajectory is moving backward. They’re defending rights that power systems are trying to take away—which we should be ashamed of. We should be the ones moving forward.

AV: What did you make of the latest WikiLeaks releases regarding Guantanamo Bay detainees?

Chomsky: I’m glad they’re released. They tell us more about what we basically knew, that a lot of innocent people—or people not known to be guilty, that’s the important thing—are being subjected to extremely harsh treatment.

Actually, you know, in a sense all the talk about Guantanamo is kind of beside the point. I mean, once Guantanamo began to be used, before anything happened, you knew it was going to be a torture chamber. Why else send them to Guantanamo? I mean, if you have charges against somebody, in a civilized society you present the charges in court. If you can’t do it, you send them to a torture chamber. Even without the early leaks, everyone should have known right way Guantanamo is a torture chamber. Otherwise there’s no reason to use it. And they picked Guantanamo because of the assumption that it would be out of the reach of American law.

AV: I heard a man call in to radio show on NPR to suggest Guantanamo detainees against whom there was no clear evidence of a crime should simply clear up matters for us by providing proof of their innocence.

Chomsky: That’s back to the medieval period. You’re not supposed to present proof of your innocence. Suppose you’re arrested for child abuse. Are you supposed to prove you’re innocent? That’s a sign of how radically much of the population has just lost any concept of the rule of law.

But you know, that’s true of everything. Take, say, drone attacks in Pakistan. According to polls, they’re pretty much supported. Suppose in the 1980s that Russia had been carrying out drone attacks in Pakistan. Pakistan was the base—the open base, there was nothing secret about it—for the attacks on Russian soldiers in Afghanistan. Would we have accepted it?

What would have happened is we would have had a nuclear war. Because if the Russians even tried that, there would have been a tremendous reaction. But when the US does it? Okay, fine.

Noam Chomsky

Thursday, May 12, 7pm. Montante Center, Canisius College. $15 members, $25 nonmembers

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n18 (week of Thursday, May 5th) > American Bombs: an Interview with Noam Chomsky This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue