Remembering Pete Hill

by Ryan Whirty

How a baseball legend spent his golden years in Buffalo - and no one noticed

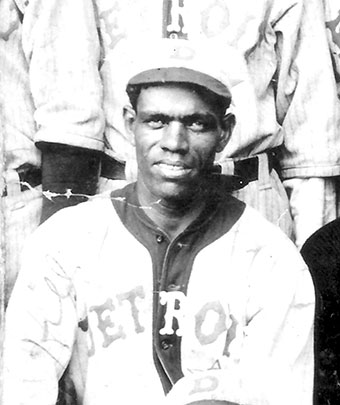

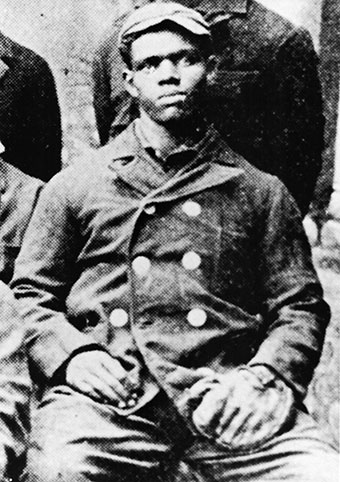

In December 1925, Baseball Hall of Famer John Preston Hill, commonly known as Pete, sent a note to the Baltimore Afro-American, a leading African-American newspaper, about how he was finding life in Buffalo. Hill was a transplant to the city, a Virginian by birth who settled in Buffalo after a storied career in black baseball that spanned several decades and earned him the admiration and respect of countless teammates, opponents, and fans.

But despite his roots in warmer climates, Hill reported to the Afro-American—he had most recently managed the Baltimore Black Sox—that he loved living in snowy Buffalo, even in the winter. Part of the attraction? Baseball, naturally.

“I arrived here sometime ago and found Buffalo to be a very lively burg,” Hill told the newspaper. “I expect to remain all winter. I am with my old time friend, ‘Home Run’ Johnson, with whom I used to play on the old Cuban Giants. Johnson is very anxious for me to remain here and help him put a club in here next year, as this is a good baseball town.”

Hill first arrived in Buffalo over the winter of 1925-26, and he ended up enjoying Buffalo so much that he spent the entirety of his sunset years in the city. He worked for the Delaware Lackawanna and Western Railroad for many years as a porter, even helping his old mate Grant Johnson, also a legend in black baseball circles, organize a semi-pro team comprised of railroad porters. Hill was living on 16th Street when he died on December 19, 1951, according to his death certificate.

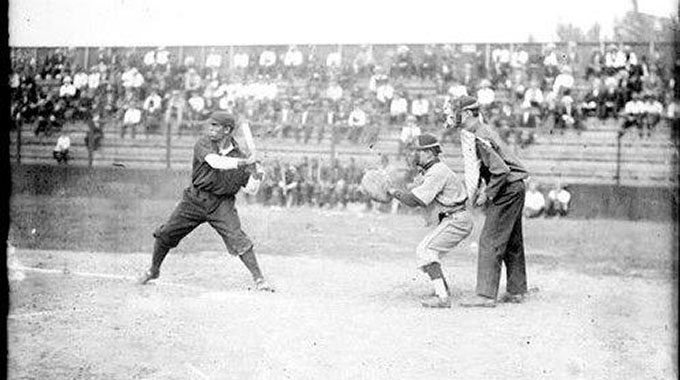

In his professional playing days, which ran from roughly 1889 to 1926, Hill was perhaps the preeminent centerfielder in African-American baseball, a talented, supremely consistent contact hitter with a near-flawless eye for the strike zone who hit for both average and power. With great speed and a powerful arm, Hill was also a deft fielder, and he was a crafty base runner who had a particular knack for unnerving even the best pitcher.

“As the first great outfielder in black baseball history, he was compared to Ty Cobb, and rightfully so,” states the Negro League’s Baseball Museum’s online resource at Kansas State University. “If an all-star team had been picked from the deadball era, Cobb and Hill would have flanked Tris Speaker to form the outfield constellation.”

However, despite his prowess on the diamond and the high esteem in which he was held by baseball historians and devotees of black baseball, Hill was somewhat overlooked by the wider baseball community, partially because much of his career took place before the creation of the formal Negro Leagues—the development of which relied heavily on the contributions of Hill and other baseball pillars.

A paucity of detailed box scores and reliable statistics from the late 19th century and early 20th century also contributed to confusion about his abilities, says Gary Ashwill, a North Carolina-based researcher who has uncovered much about Hill’s career.

But thanks to a vast improvement in research methods and resources over the last decade, Hill’s career has been greatly filled in, so much so that he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 2006. With his enshrinement, Hill began to get the recognition many felt he, as well as his contemporaries in black baseball history, deserved.

“A lot of people forget about the baseball players who were pioneers in the game,” says Ron Hill, Pete Hill’s great nephew. “They’re forgotten like they never existed, but they were a part of American history.”

He added with pride, “How can you talk about baseball without talking about Pete Hill?”

But even membership in the Hall of Fame featured vagaries and downright ignorance about Pete Hill. His original plaque at the Hall of Fame incorrectly listed his name as Joseph Preston Hill and his birth home as Pittsburgh, where Hill spent much of his youth and early playing career and where Ron Hill and other descendants still live.

However, subsequent research produced contradictory information, first discovered by Ashwill and others and later fleshed out by a team of dedicated people, including his great nephew and Zann Nelson, a journalist/historian in Culpeper County, Virginia.

Once the Hall of Fame confirmed the results of the research—most importantly, that he was born in Culpeper and named John Preston Hill—it recast Hill’s plaque and held a formal re-dedication ceremony in Cooperstown in October.

But while Hill’s origins and youth are now much clearer, the legend’s latter years, especially the ones he spent in Buffalo, remain clouded with mystery. Even Ron Hill was originally unaware that his great uncle essentially retired to and died in the city.

“Between the years of 1930 and Pete’s death in 1951, there is little known other than his occupation and places of residence,” Nelson says. “Time has destroyed memories, buildings, and records that may offer more clues to Pete’s life in Buffalo.”

In addition, Nelson says, Hill probably kept a low profile and went about his life as a railroad porter and part-time ballplayer unassumingly. “I think it is safe to say that Pete led a quiet life,” she says.

As a result, Buffalonians are largely unaware that a baseball legend lived here for a quarter century. Because Hill was on the downside of his career and didn’t play for high-profile teams in Buffalo, the vast majority of the community, even the African-American population, doesn’t even know he existed.

“Pete came to Buffalo when he was 43 years old,” Ashwill says. “His days as a star player were long over, and his baseball activities in Buffalo mostly consisted of organizing semi-pro or amateur teams. So Hill was largely off the radar, as far as the black sporting press was concerned.”

In fact, the national media seemed to pay more attention to Hill than the media in Buffalo. A Chicago Defender article from December 1942 details Hill’s trip to Chicago, where he spent his prime playing days as a member of Rube Foster’s powerhouse American Giants, to visit his son, who was on furlough from the Army.

In addition, legendary Defender sportswriter Fay Young noted Hill’s passing in a December 29, 1951 column in which Young writes that Hill “helped put Negro baseball on the map.”

However, there exist few, if any, media accounts in Buffalo of Hill. Local historian Howard Henry, a lecturer in the Health and Wellness department at Buffalo State College, said he hasn’t found any references to the ballplayer in the local black press from the time and what little Henry has gleaned has been through official records like city directories.

According to those directories, Hill moved within the city several times between 1933 and his death in 1951, including residences on Eagle, Cedar, North Division, and 18th streets. Hill frequently lived on the same property with Johnson, his ballplaying friend, sometimes occupying a house in the rear of Johnson’s main house.

The final listing for Hill in the 1951-52 directory is 168 18th Street, which would seem to indicate he was living at that address when he died. However, Hill’s death certificate lists his residence as 168 16th Street.

Hill made his living as a porter for the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, which linked the coalmines in Pennsylvania’s Lackawanna Valley to upstate New York. The railroad and its lines have since been sold, resold, and broken up between other companies and public authorities.

According to DL&W records, Hill worked as a porter under the title “baggage, parcel room and station attendants” consistently from 1937-51, sometimes making as much as $2,700 a year.

It was through his job as a porter that Hill continued to play baseball, joining Johnson on the semi-pro Buffalo Red Caps, named after the tradition porter chapeau. However, there is little other information about the specifics of Hill’s post-Negro Leagues baseball career. Ron Hill says those around Pete at the DL&W weren’t even aware who he was.

“When he worked for the railroad, people didn’t know about his baseball background,” Ron says. “I don’t think it was a very good team at the railroad, but he still wanted to play baseball.”

A few details about Hill’s life in Buffalo can be gleaned from official government records. His application for a Social Security card in January 1937 lists his address as 113 Eagle Street, a location not listed in any of the city directories. His employment as a red cap for the railroad is stated, and his place of birth is identified as Rapidan, Virginia, the son of Ike Hill and Elizabeth Seals. The date of birth reported is October 12, 1884.

A little more information is gained from Hill’s death certificate from December 19, 1951, which lists his cause of death as coronary thrombosis, or heart attack. The place of death is stated as “Elmwood Ave. at Tracey,” presumably the intersection of Elmwood Avenue and Tracy Street. Ron Hill says Pete died at a bus stop on the way to his job at the railroad. Henry discovered that Meadows Brothers funeral home, which is no longer in existence, managed the arrangements.

According to the certificate, Hill was divorced from Gertrude Lawson, whom he married in 1906 or 1907, when he was just entering the prime of his baseball career. The couple had one son, Kenneth, while living in Chicago. Kenneth died in 2001.

The death certificate contradicts Hill’s Social Security card regarding date of birth: The card says Hill was born on October 12, 1884, but the certificate lists the date as October 12, 1882, which would have made Hill 69 years old at his death.

The death certificate seemingly muddies the waters of Hill’s origins by listing his place of birth and his parents as “unknown,” unlike his Social Security card. Such discrepancies reflect the scarcity and imprecision of official documents decades ago, especially regarding African-Americans of Southern origin.

After Hill’s death, his body was transported to Chicago for burial, but for decades the exact location of his grave was unknown. Recently, the same network of historians and researchers who clarified Hill’s birth information finally discovered the legend’s final resting place.

Now, nearly 60 years after his passing, those dedicated researchers have uncovered more information about Hill’s life than ever before. The work of historians like Nelson, Ashwill, and Henry, as well as the dedication of Ron Hill and other family members, has filled in the picture of a man and baseball player who rivaled the more well known Major League greats of the early 20th century.

That crusade led to the correction of Hill’s Hall of Fame plaque last fall, and it uncovered crucial, albeit somewhat vague, details of his golden years in Buffalo. It’s also brought peace of mind to those who knew him, like Ron Hill, who says he was aware that his uncle Pete was a baseball player but had no idea that he was a Hall of Famer.

“It kind of slapped me in the face,” Ron says of uncovering his great uncle’s career. “I didn’t know how great he was…to me, he was one of the all-time great baseball players.”

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n18 (week of Thursday, May 5th) > Remembering Pete Hill This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue