The Fateful Trip

by Jack Foran

At the Burchfield Penney: Burchfield, Schwanekamp, and Lankes visit Robert Frost in Vermont

The title of the exhibit is The Fateful Trip to Vermont, and how it was supposedly fateful was in terms of a road not taken. Not that Charles Burchfield was probably ever going to go very far down the wrong road for him as an artist. But the trip might have made a difference, and it makes an interesting and revealing story about his artistic sensibility. The Fateful Trip exhibit is currently at the Burchfield Penney Art Center.

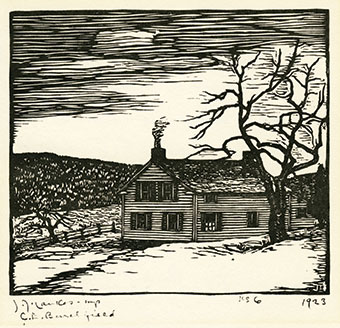

The car trip occurred in the summer of 1924. The trip cohort consisted of Burchfield and two fellow Buffalo artists and friends: intaglio artist William J. Schwanekamp, and Julius J. Lankes, who specialized in woodcuts and wood engravings, and with whom Burchfield was collaborating around that time on some woodcuts or engravings to be used as book illustrations. Burchfield would draw the designs on the wood, and Lankes would do the carving.

One of the main purposes of the trip was to visit the poet Robert Frost, then in early mid-career. Lankes had met Frost previously and was hopeful of the possibility of illustrating some of Frost’s poems or books, and in having Burchfield collaborate on the illustrations. Lankes seems to have been much impressed with Frost, and delighted with his own acquaintanceship with the poet on the cusp of renown. “I feel I could tell the world to kiss my royal stern; I’m a friend of Frost,” he wrote in a letter to Burchfield.

Burchfield may not have been as impressed with any of it. The visit was to the Frost farm at South Shaftsbury, Vermont. Frost seemed very amicable. He and his wife Elinor made dinner for the three Buffalonians, and then the poet sat up with the artists half the night talking, until, as Burchfield later wrote in a letter, “I was aching and agonizing for sleep.” The Buffalonians slept in a barn on new hay, which Burchfield said “smelled delicious,” and the next day started back home.

The trip home wasn’t so enjoyable. Several flat tires and some squabbling about expenses and such. (You know how these summer car trips can go.) The three artists remained friends, but for a while at least not as close friends as they had started out.

And Burchfield never did collaborate on any Frost illustrations. Lankes himself did woodcuts for Frost’s next book, entitled New Hampshire: A Poem with Notes and Grace Notes, which won the poet a Pulitzer, the first of an eventual four.

A score or so of Lankes and Burchfield collaborative works are on display. They include several American village life scenes and several Biblical scenes, and are mainly wood engravings rather than woodcuts, incised into the end grain of the wood block rather than the long grain, allowing for greater and finer detail in the depiction, but, as exhibit curator Nancy Weekly points out in her explanatory material, in a process that fights the hard end-grain wood, resulting in a print that is inherently stiff, and altering and flattening Burchfield’s fluid drawing style. Ultimately, she says, the collaborative work looks less characteristic for Burchfield, more characteristic for Lankes.

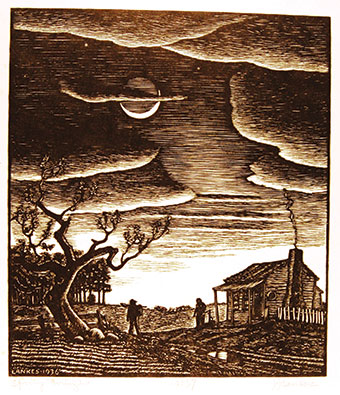

Probably just as well that they didn’t collaborate further. Three adjacent works in another part of the exhibit—one by Lankes, two by Burchfield—on similar or related subjects are revelatory as to differences between the two artists in terms artistic sensibility as well as—not to put too fine a point on it—quality of artistic imagination.

Two of the pieces—the one by Lankes and one by Burchfield—are creation-of-the-world scenes, featuring an anthropomorphic sky god creator. The central subject of the Lankes wood engraving, within an overall formidable darkness to blackness, is a clearly delineated wrathful god figure, who seems to be plunging a dagger-like lightning bolt into the heart of his creation. In the Burchfield work, in watercolors, gouache, and charcoal, the central subject is the more diverse and variegated matter of the creation chaos and turmoil, on earth and in the heavens, the spewing volcanoes and roiling streams, and turbulent storm clouds. The splendor and terrible majesty of the newly created physical environment. The creator god—neither clearly wrathful nor benevolent—is largely obscured among the storm clouds. The creator as a kind of extension of the creation. Or the creation is an extension of the god.

The other Burchfield piece is a pencil drawing—it looks like a preliminary sketch for a painting—of East Side Buffalo. A broad industrial landscape of railroads and smoke-belching factories and rows of identical worker houses whose rooflines echo the jagged patterns of the skylights on the factories, and overhead, banks of low-lying clouds of at least as much factory smoke as natural vapor.

In two steps—and all these works are from the same time period, right around the time of the collaborations and the trip to Vermont—Burchfield has moved from a literalist instantaneous creation account, without human involvement or even much in the way of human implications, to a celebration and caution with regard to the continuous creation of the natural world, with emphasis on the human role and the present moment.

These were two very different artistic sensibilities. Literalist/reductionist versus metaphoric/expansionist. The artwork on the one hand tight and flat in binary black and white but more black than white, on the other fluid of design in vivid to transparent watercolors and pure light, the interpenetration of colors, and colors and light, emblematic of the interpenetration of material and spiritual realities. The ubiquitous energy pulses, the vibrational vitalist semantic, the synesthesia.

Also in the exhibit are a handful of excellent Schwanekamp works depicting downtown Buffalo architecture and alleyways and street scenes. A horse and cart at the Chippewa farmers’ market. An alleyway perspective onto a portion of the present ECC building (it looks like).

The Fateful Trip exhibit continues through October 2.

—jack foran

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n31 (Week of Thursday, August 4) > The Fateful Trip This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue