Tabloid

by George Sax

Prisoner of Love

Tabloid

The acclaimed American documentarist Errol Morris can’t have known about the mass-market British newspaper and telephone hacking scandal that would transpire this year when he began his latest non-fiction film, Tabloid. That noxious scandal has billowed out to trap members of the United Kingdom’s favor-seeking political elite who chummed around with media monarch Rupert Murdoch and his increasingly implicated, rule-breaking corporate executives.

Morris’ slyly offbeat film has its origins in the now-innocent-seeming, pre-Thatcherite era of the mid- and late-1970s in the United Kingdom, before vulgar faux celebrity became a mercantile commonplace. Tabloid isn’t really about journalist ethics or corporate crimes and misdemeanors, although it relies on the British press of that era to move its story. It’s focused on a woman who’s both an original and an identifiable American product. She’s Joyce McKinney, whose very strange and flamboyantly obsessive adventure 34 years ago gave the famously sensationalist British popular press highly profitable grist for its insatiable mills.

McKinney was a modestly pretty small-town North Carolina beauty queen who somehow met a very young Mormon named Kirk Anderson in her home state. (The autobiographical facts and stories —particularly those related by McKinney—are easily seen as unreliable and of varying coherence. The material Morris gleans from the old British tabloid reporting and a couple of case-hardened veterans of that milieu is more convincing.) What seems beyond reasonable dispute is that McKinney followed young Anderson back to Salt Lake City. After he left on an evangelistic church mission in England, she wound up in LA, where she eventually earned enough money—just how is the subject of contention—to hire a private pilot (it’s never clear why she thought she needed one) and a security guard to assist her in her mission: to abduct Anderson at gunpoint from a Mormon facility near London and take him to a cottage in Devonshire, where he was tied to a bed and made to have sex with her for three days. That was the police and press version anyway, but McKinney insists she was only engaged in a mutually agreeable romantic reunion and that she and Kirk planned to marry. (He refused to participate in the film.)

This folie d’amour was a jackpot for the sensationalist press of the day, especially the Daily Express, whose assigned reporter, Peter Tory, tells us, “It was the perfect tabloid story.” It was delightfully weird, shocking to those willing to be shocked, and salacious. At least two of the tabs pursued Joyce and the story back to the States, where things became even stranger.

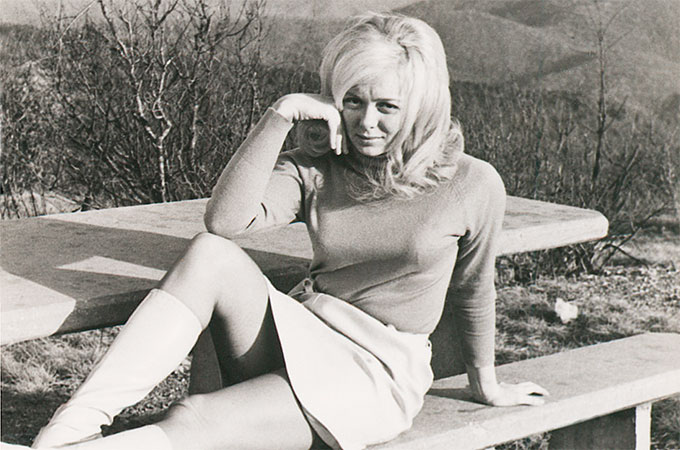

At the center of this diverting and madcap tale (emphasis on mad) is McKinney. She sits in front of a mottled gray backdrop, seeming to thoroughly enjoy her opportunity to narrate in an intensely self-dramatizing, dizzy fashion her version of the story the press, she says, used to “slander” her years ago. Morris, just off-camera, helpfully prompts her. (“What were his favorite foods?” “Did he still have the erection?”) He also interjects old photos and home movie clips, newsreel footage, jokey animation, and superimposed flash titles to underline and obliquely comment on her rendition.

Years ago, Morris told a film-studies scholar that his films are built on attempts to capture their subjects revealing themselves in their own voices. This is perhaps most importantly caught in The Fog of War (2003), in which Robert McNamara tries analytically to address his responsibility for the Vietnam War, as his mea culpa becomes blunted by and entangled in his own conflicted self-justification.

Tabloid is a much less substantial example of Morris’ art and expertise, but it develops an enjoyable fascination of its own. McKinney can remind you of a combination of a cheap Zelda Fitzgerald knockoff and Tammy Faye Bakker (without all the mascara). Her voice and personality here have a kind of bizarre banality. She protests at one point that she’s really just “a normal American girl.” This sentiment may be the result of her apparently delusional self-involvement, but in a sense, she is a product of American culture. And Morris has given us a perceptive and entertaining portrait of this eccentric “American girl.”

Watch the trailer for Tabloid

blog comments powered by Disqus

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n34 (Week of Thursday, August 25) > Film Reviews > Tabloid This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue