Next story: Buffalo Arts Studio bids farewell to Joanna Angie with a 20th anniversary exhibition

Three exhibits open doors into the contemporary Asian art world

by Jack Foran

East and West

Given that politico-economic world leadership seems to also translate into leadership in the arts, Melissa Chiu, director of the Asia Society museum in New York, did not hesitate to announce in a recent talk at UB the emergence at present of the Asian Century in art.

Appropriately enough, there are at the moment three Asian-oriented art exhibits in the area, one at Daemen College and two at UB, one at the Center for the Arts and the other at the Anderson Gallery. The Daemen and UB Center for the Arts exhibits are related to art instruction exchange programs between the local schools and schools in China. The Daemen exhibit is more about art proper, painting and other media. The UB Center for the Arts exhibit is more about the cultural exchange experience. Both ways are good. The Anderson Gallery exhibit consists of a dozen videos about women workers in the municipal trash recycling program in what is now officially called Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, and trash-component sculptures by Vietnamese artist Dinh Q. Lê.

Chiu’s wide-ranging talk touched from various angles and perspectives on the key aspect of contemporary Asian art of the amalgam of traditional and experimental.

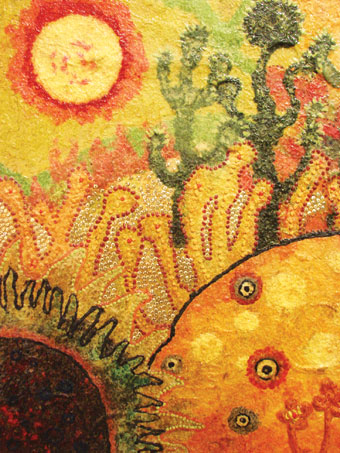

The amalgam is nowhere more in evidence than in the Daemen artworks, which are by Chinese faculty members as well as students in the exchange program, which is with the South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China. Interesting to see that in terms of the traditional/experimental opposition, the faculty works—a number of which are stunningly beautiful—tend much more toward the traditional, the student work much more toward the experimental. Tradition is something you learn.

Among the best of the faculty works, an ink on paper painting by Li Lin features two great circles, the one containing a still-life arrangement of two pots with flowers or other vegetation and a small table and a chair, the other a smudge circle breaking into a spiral form. The cosmic universe and the universe of art, perhaps. The minimal-gesture masterly brushwork is reminiscent of Chinese calligraphic art.

Yihong Yuan has an exquisite celadon green porcelain plaque with relief sinuous figure of a woman walking on clouds possibly, possibly on lotus flowers on water.

Min Feng has a silkscreen depiction of a mountain agricultural village—a jumble of unpretentious houses and farm carts and tools and animals—reminiscent of the Chinese traditional genre of whole mountain views, with off in some misty recess of the mountain a sole sign of human presence, a single habitation, and usually a human or two, but idle, as if in a meditation, echoing the observer’s meditation on the grandeur of nature and practical insignificance of the human part in it. But with a radical change of focus, and thus message, to the quotidian existence of the real-world inhabitants of the mountain environment, and active versus contemplative life, and positive revaluation of the human individual in the light of the quotidian struggle for survival.

And Yan Wang two superb handmade paper works very faintly dye-colored and with wet-stage impression patterning, in the one case with vertical and horizontal grid lines, in the other with Jackson Pollock reference water drop flow lines.

Among the student works, Peng Li has a impressive oil on canvas high-angle view of a densely constructed city of medium high-rise buildings extending outward as far as the eye can see, and below, toward the street level, into an impenetrable blackness.

And Lei Yang an excellent mixed-media landscape abstract in foreboding dark hues in a series of scarcely distinguished horizontal zones suggesting sky, distant land mass, less distant land mass, and foreground water body.

The UB Center for the Arts works are collaborative works between UB students and students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, sometimes with art faculty in on the collaboration.

A three-channel video installation by Katrina Boemig, Yang Xin, Necole Zayatz, and Luo Wei is specifically about the exchange experience. In imagery and words, sometimes aural, sometimes as text, sometimes in English, sometimes in Chinese, sometimes in sign language, the work is about the difficulty of communication across cultural, and particularly verbal language, barriers. As the sporadic on-screen text states, “Some things were impossible to translate…but we will try again and again…And that’s what makes us all the same, and that’s what makes us all different.”

The collaboration between Christopher Fox and Liu Ling Zi is about the discovery of similarities as well as differences between cultures. A portion of their work consists of photos of industrial ruins or remnants in Buffalo, and strikingly similar industrial remnant scenes in Beijing. Another portion consists of impromptu video interviews of Beijing residents, confronting them with the question, “What do you seek?” In broad or specific terms, however the interviewee thought to interpret it. Some were dismayed and declined to answer. One man kept repeating, “It’s hard to say. It’s hard to say,” and finally said, “This is a torture.” Several of the interviewees said, “Dreams.” One old man said, “There are no dreams left.”

Another work, called Glass Box, is a by Luo Zilong, Marc Tomko, and Caitlin Cass. It consists of a large wood and steel walk-in box, in the center of which, on a pedestal, is the glass box, quite empty, of the title. A kind of physical Zen—Chan in Chinese—koan. On the inner walls of the large box are myriad drawings and notes in English and Chinese and math, some seemingly related—but in cryptic and enigmatic ways—to the glass box mystery, some possibly not.

The Anderson Gallery show is called Saigon Diary (the city is still familiarly known as Saigon) and comprises 12 videos following the trash collection for recycling activities of 12 women in 12 different municipal districts. The recycling program is light years ahead of recycling programs in this country. It looks like they recycle everything—bottles, cans, paper, plastics, cardboard, rubber, metal, whatever—little or nothing goes to landfill. And the program generates work.

In addition to the videos, the exhibit includes a dozen or so of the artist’s sculptures from trash. These range from gaudy elaborate—a huge kind of hanging screen of mostly beer and pop cans, but lots of other junk as well, called Shanty Town Composition—to simple elegant—a work consisting of a roll of corrugated metal standing upright and a sizable rock, called The High-rise of the Future.

Recycling is a novel activity in Vietnam, occasioned by the tremendous amount of mostly useless stuff flooding the country now that it has gone thoroughly capitalist, following the war we fought and lost to stave off Communism. Lot of dead soldiers, on both sides, scratching their heads.

Tomorrow (September 30) is the final day of the Daemen exhibit. The UB Center for the Arts exhibit runs through October 22, and the Anderson Gallery exhibit goes through December 31.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n39 (Week of Thursday, September 29) > Art Scene > Three exhibits open doors into the contemporary Asian art world This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue