Murder on May Street

by Charlotte Hsu

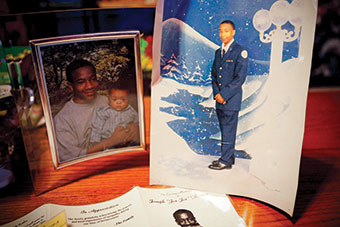

Who killed Joseph Thomas Jr.? It’s been more than seven years, and still his family has no answers.

There was nothing extraordinary about the murder of Joseph Thomas Jr.

He was 19, black, and a resident of one of Buffalo’s many poor neighborhoods. Police found his body on the floor of a home at 302 May Street, just south of Genesee Street on the city’s East Side.

Joe Joe, as his family called him, had been shot at close range.

A friend sitting on a couch in the same room was also dead. He had been playing video games. The TV was still on when officers found the men.

As far as killings go, Joe Joe’s, which took place on a mild summer’s night in 2003, was nothing remarkable. Most homicide victims in Buffalo are male. Most are black. Most die in shootings.

Police never found Joe Joe’s killer.

But that’s not unusual, either. And in this way, his passing, however ordinary, haunts us. Seven years after the fact, whoever fired the shots that bled the life from his body might still be out there, walking free.

•

Sometimes, at neighborhood cookouts or at the store, young men who knew Joe Joe will approach his father, Joseph Thomas Sr., to say hello.

“Hey, Mr. Thomas,” they might say, or, “Hey Mr. Joe, how you doing?”

Thomas, 50, will summon a smile. But as he exchanges greetings with his son’s friends, the old suspicions will return.

When police arrived at the scene of the double-murder on May Street in 2003, they found no sign of a break-in.

That evidence led investigators to conclude that Joe Joe and the second victim, Louis Brown, 19, likely knew their killer or killers. Death came to the door, and Brown and Joe Joe let their assailant in.

So when Thomas runs into kids who knew his son, the same silent question always commands his thoughts: “Was it you?”

“I’m leery of a lot of people that knew my son, you know?” the father said. “I wonder.”

•

The call that drew police to 302 May Street after midnight on August 24, 2003 came from a pay phone. The tipster was anonymous and reported only that some unknown trouble had occurred at the house.

Homicide detective Patrick Judge arrived at 12:38am. With fellow officers, he surveyed the sparsely furnished residence, which Joe Joe’s mother, Mildred Thomas, owned.

The video game console was out. From the position of the victims’ bodies, Judge deduced that the outbreak of violence had taken them by surprise. At least one of the two men appeared to have “no clue that this was coming,” Judge said.

In the days that followed, police canvassed nearby homes and streets.

“We’d go around the neighborhood, talk to people, see if we could get anyone solid,” Judge said. “Nobody had seen anything.”

Evidence officers collected at the scene yielded no leads. Very quickly, the case went dead. A few tips came in between 2004 and 2006, but Judge and his partners were able to rule out every suspect they investigated. From the scant information they had, police could not surmise a motive.

Thomas said that before Mildred owned 302 May Street, drug peddlers had sold marijuana out of the place. As far as Thomas knew, however, Joe Joe smoked weed but didn’t deal.

Still, in stories reporting on Joe Joe’s death, the Buffalo News described two previous events that pointed to a dark side of the young man’s life. First, Joe Joe had been shot in the abdomen on Goodyear Avenue in 2002. Soon after, police purportedly caught him driving with a gun in his car. Joe Joe died wearing a colostomy bag, a vestige of the earlier violence.

Judge said his unit had no clues linking the double homicide in August 2003 to any other case. For that reason, he said, investigators did not revisit the Goodyear assault or interview two men arrested in connection with that shooting.

Buffalo is a small town, with a population of about 270,000 on about 40 square miles of land. People talk. But no one spoke up to police about what had happened to Joe Joe and Brown.

Maybe no one witnessed the murders, other than the killer or killers. Maybe the urban grapevine stayed silent on the subject. Then again, maybe someone out there is still keeping a secret.

“I can’t say if there was anybody else there at the time or not. There very well could have been,” Judge said. “In a lot of cases, there are people that are there and don’t come forward. And that really bothers us…A lot of our cases would be solved if people came forward. There’s always people.”

•

In their memories, friends and relatives will set aside Joe Joe’s vices and mistakes. What they will remember is a good kid, a boy who loved family, sports, and his father’s chicken noodle soup. He listened to rap, but borrowed Thomas’s music—oldies like the Temptations and the Stylistics—for dates with girls.

Not long before his murder, Joe Joe had graduated from Seneca Vocational High School and enrolled to study information technology at Bryant & Stratton College, relatives said.

In any given year, the number of murders city police solve—including cold cases—is equivalent to about half the number of new homicides recorded, said department spokesman Michael DeGeorge. Joe Joe’s killing was one of 60 in Buffalo in 2003. Investigators have cleared 27 of those.

Mildred held onto hope, believing until the day she died in 2009 that detectives might catch the killer. Before she passed, she would call Judge several times each year to ask about her son’s case.

Thomas coped with loss in a different way: He dissolved his pain in a cocktail of drugs and beer, binging on poison for 11 months after the shooting.

“Got to the point where I was drinking a 30-pack of Millers a day,” he said. “Lord knows how much alcohol…”

His voice felt heavy with the memory.

“I was just lost,” he said, simply.

He nodded. He has eight other children, by blood and marriage, but Joe Joe was his only biological son.

Following the Goodyear assault in 2002, Thomas had insisted that Joe Joe move to Amherst to live with Thomas and Thomas’s new wife. The goal was to keep the boy away from the city.

But suburban life bored Joe Joe, who griped that he missed his friends. He begged to return to Buffalo. Thomas said no. Seeking an ally, Joe Joe turned to his mother. Mildred petitioned Thomas again, and finally, the old man caved.

Thomas thinks about that a lot—how he changed his mind.

•

On a wet afternoon in July 2010, Thomas stood at the heart of a crowd of maybe 100 people who had convened at a paved lot on Jefferson Avenue by Riley Street to protest violence.

Nearly seven years had passed since he lost his son. His almond-shaped eyes, huge behind the lenses of wire-framed glasses, betrayed few emotions. But his posture—head bent, with a slight slouch—was that of a question mark.

News cameras rolled. Off to one side, a reporter interviewed a mother who lost her son. Police found the killer in that case. Speakers expounded in generalities about the importance of cooperating with police, but even within this coterie of activists, who, really, could understand what it’s like to live without closure?

In the aftermath of Joe Joe’s murder, Thomas’s low point came on July 31, 2004, a Saturday. He had picked up a prostitute, taken her to a motel to smoke crack, then followed her to a house on Goodyear to continue their bender.

In his drug-fueled daydreams, he saw friends and family walking and driving up and down the street, looking for him. He stepped outside to go home but decided, before he reached his car, that he needed to finish smoking some crack he had left inside the Goodyear residence.

As he headed toward the house again, he heard a voice that he said was Joe Joe’s: “You outta there. Why is you going back in?”

Thomas got on the phone, crying, and described his hallucinations to his childhood friend, Nathaniel Beason. The two went to the first Narcotics Anonymous meeting they could find, and Thomas has been clean since August 1, 2004.

Hoping to make a difference in the city, Thomas has moved back to Buffalo, renovating his father’s old home, a buttercup-shingled bungalow near Fillmore Avenue on the East Side.

A contractor, he does business six days a week. On Sundays during football season, he watches the Buffalo Bills. He has season tickets. He takes joy in family.

Still, the old grief returns, often at random. He’ll be working, having a good day, and then, all of a sudden, tears will be falling again.

It bothers him that he can’t trust people in the neighborhood. But he can’t help his suspicions. On TV, he watches crime dramas—CSI, The First 48—and hopes the day will come, too, when investigators figure out who gunned down his son.

Thomas would love to ask the killer: “Why?”

He has imagined what he might say: “What prompted you to do this? Did my son do something to you? Or did Louis do something to you? What prompted you to go in there and do this? I would love to know.”

•

Fifty-five people were murdered in Buffalo in 2010. As of the start of this month, police had cleared 21 of those cases. Some slayings, like the City Grill shootings that ended four lives last August, dominated headlines for days. Other homicides had a lower profile.

Murders of the ordinary lot—ones like Joe Joe’s shooting—don’t capture our imaginations. He is one of hundreds of victims just like him: another young man, killed in another shooting.

But Joe Joe’s death was extraordinary for at least one reason. He was Thomas’s son: not just a 19-year-old kid with bad habits, but a boy who loved to race in the soap box derby; a teenager who devoured his dad’s chili; a college-student-to-be who struggled to build the right kind of life for himself.

Buffalo’s not a big city. Maybe you met Joe Joe once—sat next to him at a Bills game, or waited behind him in line at the grocery store. Maybe you know him.

For Thomas, talking about the murder is difficult. But he worries that if he doesn’t tell the story, we’ll forget about his son.

Maybe someone will read this article and step forward with information, Thomas said. Maybe someone who knows what happened to Joe Joe will decide the secret isn’t worth keeping anymore.

Maybe, Thomas said.

He won’t surrender hope.

Anyone with information on the case can call or text the Buffalo Police’s confidential tip line at 716-847-2255. To report a tip online, visit www.bpdny.org and click the “Report a Tip” link.

Charlotte Hsu is a freelance contributor to Artvoice. A former reporter for the Las Vegas Sun, she writes about Buffalo at buffalostoryproject.com. Christina Shaw’s work can be found at christinashaw.tumblr.com.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n4 (Week of Thursday, January 27) > Murder on May Street This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue