A Procession to Black Rock with Torn Space

by Anthony Chase

Dan Shanahan’s latest production re-infuses the Theosophical Society with ritual

Torn Space Theater’s current offering is called Procession. This is another of Dan Shanahan’s original and elaborate site-specific experiences. The avant-garde director has previously lured us into such off-the-recent-path locations as the Dnipro Ukrainian Center on Genesee Street and the abandoned Central Terminal. Now we’re off to Buffalo’s Black Rock neighborhood to process down the aisle, across the ceiling, and into the apse of the Theosophical Society building at 70 Military Road.

The building was formerly the Immanuel Church of Christ, home to an early 20th-century German evangelical congregation. With its stained-glass windows and handsome woodwork intact, the structure is in an impressive state of preservation. The history of a religious sanctuary is not lost on Shanahan, who uses the space to visually arresting effect, linking space to action as if to suggest that the building is sharing its memories.

The Procession experience begins even before the audience enters the building. Lighting designer Patty Rihn has illuminated the church windows, which pulsate in the night in a manner that suggests that the building is alive. This show of light attracts the attention of enthusiastic neighborhood residents, and welcomes the public to draw near.

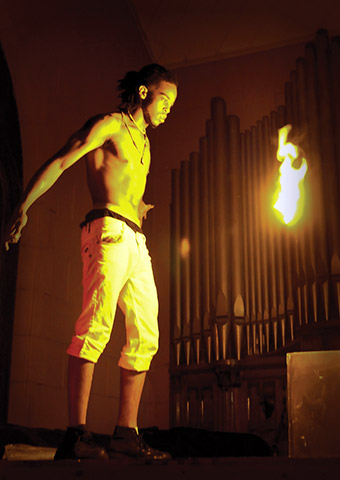

As the performance begins, the building begins to breathe, courtesy of Todd Lesmeister’s bold sound design, and the work of sound engineer Joseph Stocker. The apse fills with stage fog. The ceiling is illuminated with a play of light and video. Brian Milbrand provides yet another eye-popping design, and the contrast between the high-tech visuals and the antique setting is remarkable. At first we see a succession of regular lines scanning the ceiling like the readout on a medical monitor; at other times we see a flurry of geometrical shapes or a playful array of urban skateboarders.

Procession confronts its audience with a series of rituals as we enter the avant-garde realm of the “post-dramatic theater.” While the mind may strive to find sequences of narrative and connections to familiar holy and secular narratives of birth, death, and resurrection, the piece defies consistent empathy or even identification with its fragmented characters. Instead, we see a succession of ritual pieces, as characters confront each other, disassociate, regroup, and continue.

The experience may be site specific, but the impact is to provide a massage of decided disorientation. No Aristotelian cause and effect, empathy, or catharsis here. Instead, we encounter a string of visually arresting moments, assembled like an anthology of symbolic poems.

The sequences are leisurely, methodical, and ceremonial.

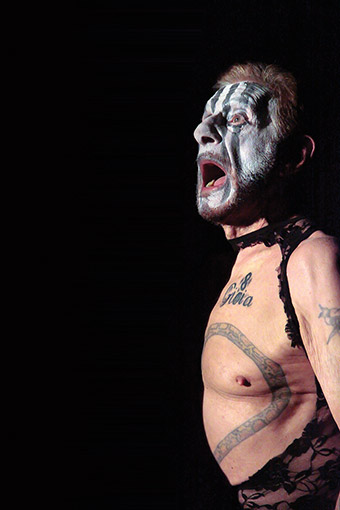

The piece, which I hesitate to call a “play” because of its joyfully counter-narrative structure, appropriately begins with John “Giovanni” Joy, as the “High Priest,” looking like a Goth version of Marcel Marceau’s Bip, making his way down the church aisle, intoning what sounds like liturgical Latin.

We see the procession of the pink twins, one of whom inflicts violence upon the other, Cain and Abel style, before resurrection and resumption. We see the procession of the glowing vacuum cleaner, enacted by Diane Galdry, who punctuates the moment with a theatrical finish. We see a variety of sacrifice and crucifixion rituals as the procession approaches its emphatic climax and conclusion.

Throughout, we experience inventive play of light, video, and sound, populated by the keen crew of actors who, in addition to John Joy and Diane Gaidry as Preparer (both of whom are masters of this genre and create riveting moments of mystical, nearly iconic vividness with seeming facility), include Carmen Swans as Choir, John Toohill as Young Man, Danielle Hermann and Renee Hermann as Twin 1 and Twin 2, Christopher Titus as Sacrificial Figure, K. Cornelius as musician, and Jim Abramson and Justin Rowland as Drummers.

My one quibble is that with such energy and effort invested in the stunning vision and sound of the production, at times Torn Space seems to forget that an audience will be coming to the performance. The walk across the dark and uneven lawn of the building is alienating. Once inside, it is too dark to read the program—I’m still not entirely sure who played each role—and there are useful notes that I did not see until I got home. Upon entering the building it is not clear where one is to go. As I entered the sanctuary, a young man intercepted me and urged, “The side aisle!” to which I responded, “What about the side aisle?” It was too dark to see that there even was a side aisle. Then, as my eyes adjusted and I saw equipment installed in the center aisle, I realized, “Oh! You want me to walk down the side aisle?”

I understand a certain degree of theatrical alienation (as when Torn Space blinded us with fluorescent light in anticipation of our momentous entry into the vast and cavernous Central Terminal space for Terminus—an unforgettable coup de avant-garde-teatre), but in this instance, more attentive audience management would be appropriate and appreciated.

The overall impact of Procession is celebratory and momentous. The piece is imbued with a mystifying sense of occasion that is the Torn Space signature. Indeed, with its avant-garde incursions into once glorious neighborhoods, Torn Space is accumulating a performance celebration of Buffalo’s past, one neglected space at a time. It is a thrilling and wondrous procession.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n40 (Week of Thursday, October 6) > A Procession to Black Rock with Torn Space This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue