The Eyes of the Skin at Burchfield Penney

by Jack Foran

Architecture and the Senses

A new exhibit at the Burchfield Penney Art Center is about rethinking architecture radically. It has at this objective in a number of ways.

The inspiration for the exhibit is the work of Finnish architect Juhann Pallasmaa, who proposes an architecture less oriented, as traditionally, toward the visual sense and more toward the other senses: hearing, touch, taste, and smell.

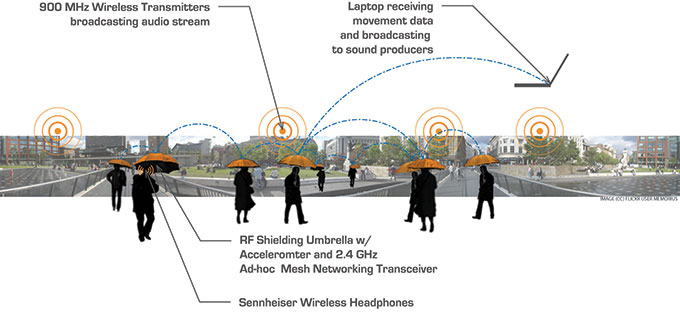

The basic idea of architecture is protection from the environment—the wind and rain and snow. In line with this idea, an installation by Mark Shepard features umbrellas. Special umbrellas, said to be made of electromotive-force-shielding fabric, to allow participants moving around in the installation’s special environment to select one among a barrage of radio frequencies transmitted within the environment and screen out the rest.

So, the umbrellas not only provide protection from the environment but also allow for the creation of an alternate environment, which is what architecture really does—and in this case, by collaboration of artist and audience. For the umbrellas are also equipped with custom electronic apparatus to feed back locational data to the artist at the radio transmitter (sending out all those different radio frequencies), allowing him to modify the sound stream according to the movements of the participants. These modifications, in turn, will influence the participants’ movements.

An installation by Alexandra Spaulding consists of a little white room—white walls and ceiling, though grass-green carpet floor—and a white chair you sit in to listen on a white record player to a white vinyl LP record. With a hint of reference to the Beatles’ White Album, the record was made at the Abbey Road studio, London. However, that’s the extent of the reference. This is not Beatles music.

Not even music, really, but a kind of symphony in four movements of basically non-tonal sounds. Typically, variations on a wash of nondescript background sound to crescendo and decrescendo pulsations that gradually become more and more emphatic. Other times, weathery sounds that threaten to grow stormy, but then resolve peacefully. Or hums and drones. Only in the last movement, some briefest duration peeps of tonality, like cosmic signals we recognize as signals, but don’t understand the meaning of.

An aural environment intended, it seems, to elbow out all other environment, at least for the duration of the LP—pretty much the way music regularly does when we really listen. But in this case, music empty of aesthetic content, or trying to be.

J. T. Rinker’s aural sculptural piece consists of a wood plank with attached metal strip and accompanying sound component—words and noise so faint you can hardly make anything out, but apparently a talk on sound production that causes the metal strip to vibrate. You’re encouraged to touch the metal strip with your finger or forehead to pick up the sound vibrations that way. Good as far as it goes, but you still can’t decipher the words if that’s an objective.

It’s an interesting work and a handsome piece of sculpture, but what it has to do with architecture is hard to say. Also hard to know how these sometimes somewhat flip artworks—umbrellas to shield and select from multiple radio transmissions, which is what radios do that already—answer to Pallasmaa’s supposedly serious appeal for architecture that addresses other senses than the visual.

But what the exhibit does at a minimum is emphasize that the aural element is an environmental element, like the wind and the rain, that architecture needs to consider and sometimes shelter us from. This is particularly so in a time when noise is everywhere—even aggressive noise or passive aggressive, as noise is used more and more as a means to appropriate space, as in “You’re going to listen to my music cranked to about jet engine levels whether you like it or not.” That is, whether you like the imposition or like the music. It is very possibly you don’t, and this is part of the point.

And it isn’t all on one side, either. The NFTA makes its patrons waiting in subway stations listen to classical music on a sound system that no one who would choose to listen to such music would choose to listen on. Also, it’s possible that most of the patrons of the subway system would not name classical as their first musical choice for listening enjoyment.

Stefani Bardin is the exhibit curator. The exhibit title, The Eyes of the Skin: Art and the Senses, is from the title of Pallasmaa’s book, except the book has it Architecture and the Senses. The exhibit continues through May 22.

—jack foran

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n9 (Week of Thursday, March 3) > Art Scene > The Eyes of the Skin at Burchfield Penney This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue