Charles Burchfield's weather sequences at the Burchfield Penney Art Center

by Jack Foran

Talk About the Weather

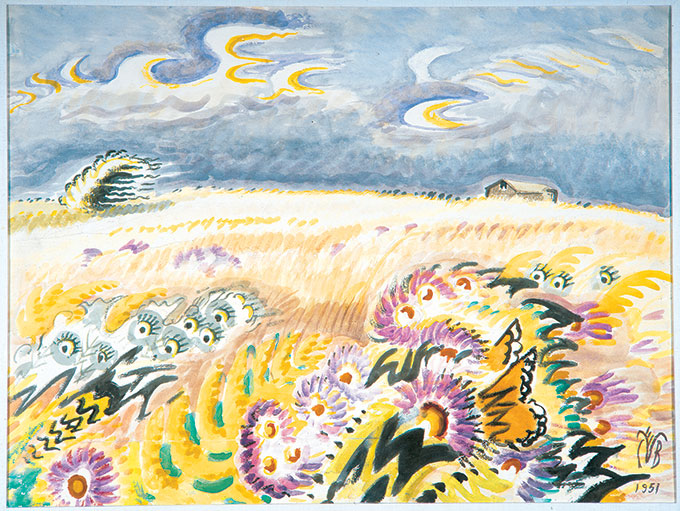

A focal point of the current Charles Burchfield exhibit at the Burchfield Penney Art Center is a half dozen or so pencil studies that show a sequence of weather events over a given all-day or sometimes several-day period.

The exhibit is about Burchfield’s iconography—the signs and symbols and pictorial strategies he employed in his artworks—particularly with regard to meteorology. But it is about more than painterly depiction of weather. It is about painterly depiction of time.

The explicit sequence of events technique is not duplicated in the finished works, the watercolors. But the iconography is duplicated, and what Burchfield learned about painting weather by means of the sequential studies does appear in the finished works, which convey time, sequence of events, more efficiently and effectively even than the pencil studies.

This excellent exhibit was put together by Burchfield Penney curator Tullis Johnson and Professor Stephen Vermette of Buffalo State College’s Geography and Planning Department. Because Burchfield usually dated his studies and often his more finished works to the day, Professor Vermette and his student, Robert Moore, were able to develop simulated weather reports for indicated days based on National Weather Service maps and records. With a smart phone you can listen in to the simulated radio reports.

A typical sequential study is an all-day sketch of conditions on July 8, 1915. It begins with a driving rain—in a verbal note on the sketch, Burchfield mentions the “rhythm of rain,” introducing an aural dimension and further time consideration—that proceeding from right to left across the sketch gradually abates, whereupon the sun peeks out from behind the clouds, and the day progresses from overcast to partly sunny. In a further verbal note, the artist describes a stand of trees as “in alternate sunlight and shadow,” quietly reprising the rhythm idea, as a unifying element for the potential watercolor.

Another study, Autumn Splendor—Storm and Winter, starts left with a peaceful scene of cathedral-like trees in their autumn glory, then proceeding right, bent with the wind and rain driving at an oblique angle. Then the storm intensifies, the angle of the rain increasing toward the horizontal, the trees bending like reeds. Followed by a placid winter scene of trees and grounds blanketed with pristine snow.

But for the artist thinking sequence, even static depiction of a weather moment implies dynamism, implies time. As for example in the watercolor from June 8, 1916, called Before the Storm, a view over rooftops of white clouds to the left, purplish to black clouds approaching menacingly from the right, and some foreground trees leaning precariously left, indicating a gusty wind conveying the imminent tempest.

Often, Burchfield’s paintings depict a moment of change from one weather situation to another, implying past, present, and future. For example, Yellow Afterglow, in which, according to the exhibit’s descriptive note, “the twilight is a momentary pause, a fleeting moment, between the movements and colors of day and night.” Or November Storm, featuring a gnarled bare tree and desiccated stalks of brush vegetation bending before a harsh wind, said to depict “a time caught ‘in between’” fall and winter. Or Clearing Sky, of which it is written, “this painting can be interpreted broadly as a metaphor for a positive change.”

All in accord with Burchfield’s fundamental program and purpose to portray the invisible by visible signs. Such as sound by wave pulses, which are visible in visible media—such as the waves on water—but invisible (ordinarily) as sound waves in air. (Then by extension, vital forces as wave pulses very much like the sound pulses. Emanations from everything alive or that ever was alive. From trees and fence posts alike.) He loves waves. For example, heat waves, which are visible manifestations (when they are visible, as above a wheat field under a hot summer sun) of something essentially invisible.

A free, handy little guide/workbook with relevant information and exercises concerning Burchfield’s weather art and his art in general, geared to young and older visitors alike, has been produced in conjunction with the exhibit. Copies are available at the welcome desk.

The Burchfield exhibit, entitled Weather Event, continues through February 26.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n1 (Week of Thursday, January 3) > Art Scene > Charles Burchfield's weather sequences at the Burchfield Penney Art Center This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue