Bonkers

by Woody Brown

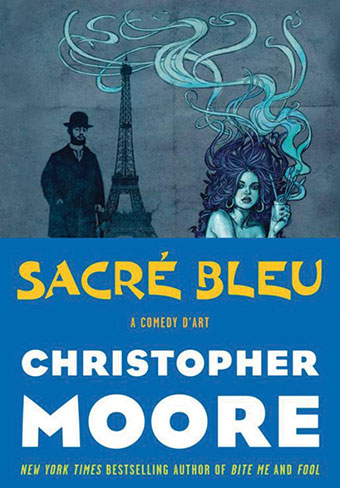

Sacré Bleu: A Comedy D’Art

by Christopher Moore

(William Morrow, April 2012)

Christopher Moore, the author of 13 novels including this, is apparently quite famous, although I must confess I had never even heard of him before Sacré Bleu. And I only decided to read Sacré Bleu after one of the employees at Talking Leaves told me it was “pretty funny, not like spit-milk-out-your-nose funny, but it’s funny.” Well said.

The novel generally follows the fictional Lucien Lessard and his partner in painterly lunacy, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the famed artist and alcoholic of diminutive stature (whose full name, were I to write it here, would probably put me past the word limit of this review). Upon learning of the death of their dear friend Vincent van Gogh, the two embark on a murder-mystery that incorporates deftly the supernatural and some of the most beautiful paintings by the major Impressionists: Pissarro (whom you may recall from the most recent abuse he has suffered, that commercial for Wheat Thins in which Alex Trebek melo-pronounces the name of his painting, Farm at Montfoucault), Morisot, Monet, Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, Degas, and Gauguin. The first edition of the novel, designed by Jamie Lynn Kerner, features beautiful cover art, color prints of relevant paintings, and a period map of Paris as the endpapers. Also, every word in the book is printed in blue ink.

Lucien, a baker and aspiring painter, is winsomely bereft of wisdom, but his friend Henri has enough drunken judgment for the two of them. Lucien, though he is ostensibly the main character of the narrative, is far less developed by the end of the novel than many of the other characters. When we meet him he is a cute kid who, like his father, and in fact like every other painter mentioned except Vincent van Gogh himself, is utterly mystified by women. He takes to heart Renoir’s teaching: “You need only find your ideal, then marry her, and you can love them all.” Thankfully, Moore treats this directive and the contemporary objectification of women intelligently, although it took me maybe 150 pages to see that. Henri is Lucien’s Leporello, a short, bass-note goofball who spends his time drinking. Sometimes he doubles as a drinker and a painter. He is certainly entertaining, but as the novel wore on, he seemed to reveal his true identity as a flat punning device. He is a direct descendent of Tyrion Lannister from George R. R. Martin’s series A Song of Ice and Fire, and also of the endlessly aggravating Captain Jack Sparrow from Pirates of the Whatever: always having sex, drunk a lot, always talking about being drunk, and periodically swashbuckling. Twice in Sacré Bleu Henri intends to unsheathe a sword hidden in his cane but discovers that he has hidden a snifter there instead.

For better or worse, Moore does not focus only on painting in the second half of the 19th century. He creates characters out of the artists and sets them on their little narrative Habitrails—welcome to historical fiction. The issue in the case of Sacré Bleu, however, is that Moore is clearly more adept at appreciating art than extrapolating plausible characters from historical sources. I got the feeling as the novel progressed that I was only going along with everything because I knew next to nothing about most of the painters who appear in the novel. Moore himself describes the similarities and differences between his characters and their counterparts in the real world in the afterword. Again, maybe this is because I am not an art historian, but I found myself finally not really interested in the factual accuracy of the text. It is a work of fiction, recall.

And as fiction, it is compelling for the most part, relentlessly unique, and insistently funny. By that I mean Moore seems to insist things are funny well past their dates of expiration. For example, at one point, a character explains the sudden departure of the maid with one word, “Penis.” The word “penis” as an explanation subsequently recurs for the rest of the novel, and it is funny maybe a third of the time. This is also a tame example of the bizarre and crass humor that pervades the novel (e.g. one character’s nickname is Poopstick; another’s is Two Cupped Hands and an Oh-Baby; also, this sentence: “It was a brilliant blue, such as he had never seen before, but it tasted like roasted sloth scrotum, which was one of his least-favorite flavors”). I don’t have the thickest skin for stuff like that, but I have skin nonetheless, and this felt excessive and lame. Maybe it wouldn’t have seemed so if it had been funnier.

Related to this is Moore’s insistence on using the verb “to bonk” in place of, let’s say, “to have intercourse with,” (or maybe even “to intercourt”). I’m not sure I can convey here how weird this word is to see in this novel, and how often it appears, and how much it destroys the atmosphere built by the text around it. Dialogue is certainly Moore’s strength in Sacré Bleu: It is quick, extremely funny, and believable. The deadpan, sarcastic timbre Moore uses for a lot of the characters, as if yes, of course he cares about the way you hear their voices in your head, is a real tonal success. But “bonk” is stunningly weak and inappropriately modern, as are, “Oh balls,” “Give me a fucking break,” and, “And fuck you, too, bears! I hope my pointy bones get stuck in your poop chute,” all of which actually appear in this novel.

The demimonde through which we follow Lucien and Henri is a charming caricature reminiscent of a Pixar film (let’s go with Ratatouille). The women are all either: 1. giggling whores in clownish makeup from the Moulin Rouge, 2. stunningly beautiful and quick-witted (but finally designing and manipulative) objects of desire, or 3. obese matriarchs who hit their sons’ love interests with frying pans. The men are all either: 1. young pining artists, 2. old pining artists, or 3. drunks (these categories are not mutually exclusive). And you know what? It totally works. Moore’s Montmartre is beautiful, bewitching, and endearing. Could the novel have done without some of the slapstick (or maybe “slapping and Poopstick”)? Yes, but then again I didn’t write this novel, Christopher Moore did, and it is unmistakably Moorish. I would certainly recommend Sacré Bleu as, at the very least, a fun and interesting bit of fiction. And while you’re at it, you should read Patrick Süskind’s novel, Perfume (1985), a darker, less funny, but better work of historical fiction. We’ll compare the two in class on Monday.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n19 (Best of Buffalo Issue, week of Thursday, May 10) > Bonkers This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue