You Can't Go Home

by Woody Brown

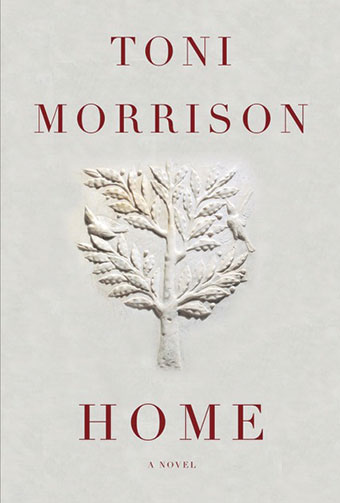

Home

By Toni Morrison ($24, 145 pages)

Knopf, May 2012

I remained unsure whether or not I should review the most recent novel by Toni Morrison (Song of Solomon, Beloved) up until the moment I started writing this sentence. My concerns were many, not the least of which being the embarrassing fact that I had never read a single work by Morrison until I read this book. I mention this not only in the interest of self-deprecation, but also to tell you that I will not be able to compare this novel to anything else she has written. But that is not necessarily a bad thing—Morrison has won a Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize in literature, and President Obama just announced that she will receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom this year, and that sounds to me like a pretty decisive verdict on her oeuvre. And anyway, a successful novel can stand on its own two textual feet, right? Home, instead of standing, opts for more of a precarious leeward list.

Morrison’s latest novel follows Frank Money, a Korean War veteran, on his search to find his sister, Ycidra. The novel begins with a dim, beautifully written recollection of a disturbing childhood scene in which the siblings saw a man being buried while still alive. In the narrative present, Frank awakens in some sort of mental hospital or other institution with no memory of how he has gotten there, but with a memory of a letter he received at some point before the book began saying only, “Come fast. She be dead if you tarry.” After a suspiciously simple escape and a brief stay with the ham-fistedly named Rev. John Locke, Frank, haunted by memories of the war, embarks on his quest. Interspersed with updates on Frank’s travails are chapters dealing with Ycidra’s life while Frank was in Korea, as well as sections that focus on more minor characters. These latter are certainly the most successful parts of the novel, especially chapter eight, which focuses on Lenore Money, Ycidra’s interestingly cruel grandmother. Most of the chapters begin with curious little italicized sections written in an almost epistolary tone. It becomes clear about halfway through the novel that these are Frank’s addresses to the novel’s narrator and his commentary on the narrative as it progresses.

That may sound compelling, but like almost everything about this novel, listening to someone describe it is probably more interesting than the text itself. As I read Home, I could imagine the author explaining the decisions she made in writing her characters’ stories, and I am positive that that would be more engrossing than the prose precipitate of those decisions. It is as if Home is a myth: the scaffold of a story that may generate fascinating secondary literature but that is itself threadbare. But Home is not always threadbare. Morrison’s descriptions of scenes and people are lush when she wants them to be, and it is in those moments when the ringing-steel timbre of her prose sounds like a clarion. She seems too often to lose interest, though, and in disturbing and noticeable ways. For instance, Frank’s grief over the loss of his childhood friend who died in the war is given weirdly short shrift: “And never again would [Frank] hear that loud laugh, or watch him entertain whole barracks with raunchy jokes and imitations of movie stars.” This memory is so nondescript that the reader can’t help but see it as an artifice.

Lit City: Literary Event Listings presented by Just Buffalo

June 11

7pm. Wordflight Reading Series: Chris Fritton and Ed Taylor, with slots for open readers. Crane Branch Library (633 Elmwood Avenue).

June 13

7pm. The Gray Hair Reading Series: Bob Borgatti, Lee Farallo, and Dan Sicoli. The three editors of Slipstream will each read their own work.Hallwalls Cinema, Babeville (341 Delaware Avenue/854-1694).

June 14

7pm. Rustling the Leaves: Reading and book-signing with Tom Wilber, author of Under the Surface: Fracking, Fortunes, and the Fate of the Marcellus Shale (Cornell University Press. Talking Leaves Books (3158 Main Street/837-8554).

Artificial may be the operative word here. Home loses its affective power when it sheds its poetic shawl and lays bare its composition, which, by the way, is the narrative equivalent of a clockwork mechanism. It is as if Morrison wanted desperately to achieve emotional results with this novel, but she was unwilling to create a story by which those results would logically follow. The tone of the italicized sections from Frank’s point of view is completely off, and jarringly so. His voice there sounds nothing like his voice during the novel’s sections of dialogue, and it is only barely different from that of the omniscient third person narrator.

Related to this are periodic insertions of some of the more creatively horrifying scenes of human depravity I have read. They come unannounced and they are shocking, but not in a successful way. They are shocking because they are disgusting and also clearly plausible. Frank’s memory of the poor Korean child who, willing to do anything to stay alive, offers herself to a soldier, is deeply disturbing, but Frank’s reaction within the narrative to this scene seems impoverished. The author counts on the reader to fill in the gaps in her characters’ emotional existences with the reader’s own personal response to shock. As we might expect, however, this leaves Frank underdeveloped, and the same goes for Ycidra. Morrison seems more than capable of imagining the revolting details, the sicknesses and sexual violence, but she does not follow her characters as they come to terms with their traumas. As Frank says at one point, “Korea. You can’t imagine it because you weren’t there. You can’t describe the bleak landscape because you never saw it.” Indeed.

I am not happy that I feel this way about a novel by Toni Morrison. I don’t even really want to write this at all because I think it’s a safe bet that Toni Morrison knows a lot more about a lot of things than I do. But any hope of me retaining any sort of authority seems pretty far gone at this point, so I’ll just go ahead and tell you—Home is also boring. I hate feeling bored. Boredom is to me an unsympathetic symptom because I feel like it is my fault, i.e. “Everything is interesting, I’m just not good at being interested!” But if I’m being totally honest, which I’m trying to be, I have to say the novel just did not hold my interest. The narrative alternated between brevity born of what felt like apathy and length born of a creativity that seemed only to accompany atrocity. Home is finally too short, and the ostensible end of the Money siblings’ story feels forced and unwelcome, kind of like when someone tells an unfunny joke and after they’ve delivered the punch line they look at you with that lit-up, open-mouthed, expectant semi-smile and all you can do is stare back at them wondering whose fault it is that you’re not laughing.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n23 (Summer Guide, Week of Thursday, June 7) > You Can't Go Home This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue