Next story: Fireworks Over the Peace Bridge Demolitions

Like Money in the (Land) Bank

Tax Delinquency

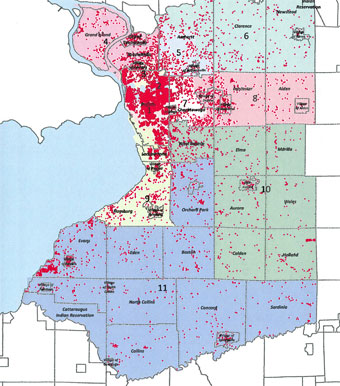

More than 70,000 properties in Erie County are in arrears on taxes and fees. (Click here to view a larger PDF version of this map.)

On the region’s new land bank, one of the first two in New York State, which has its first meeting this week

Calling it a “tool against chaos,” Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz announced the joint Erie County/City of Buffalo application for a land bank at the end of March. A notable first-100-days accomplishment for his administration, it was made all the more amazing by wrangling an agreement with a wary Buffalo City Hall that had torpedoed past land bank efforts.

A joint city/county land bank is expected to result in a notable leap forward in the region’s ability to grapple with the legacy of disinvestment and sprawl-without-growth.

Here’s how it works: The newly created, nonprofit land bank will have the power to buy and sell land; its bids for land at public auction are given priority over private bidders, so long as its bids equal back taxes and fees owed on a property. It does not have eminent domain powers. In theory, a regional land bank allows its constituent municipalities to conceive and implement a coherent strategic plan for dealing with vacant land and structures.

“In the first few months of my administration people have realized we’re all in the same boat, and we need to work together over the next four years,” Poloncarz said. “If you are addressing vacant properties in Buffalo but not in Cheektowaga, you’re not addressing the problem. All 44 municipalities in Erie County are going to be part of this.”

With Erie County acting as the foreclosing governmental unit (FCU) for all of the county outside of a city line, the county has to deal with foreclosed properties and tax liens from the Town of Marilla to the Town of Collins. It’s a dirty little secret in local government that Erie County makes those municipalities whole for unpaid local taxes on foreclosed properties—a drain on county coffers that until now there were few tools to stop up. As Poloncarz told WBEN’s Dave Debo in April, it’s a primary reason “why supervisors are able to increase budgets while lowering property taxes. It’s a kind of regionalism folks don’t know exists.” With the county already paying the piper, the land bank will provide welcome tools to give it a role in calling the tune.

Who's who at the land bank

“The dynamics are important. We want the board to be very action-oriented,” Mehaffy told me in March. And Kildee has said, “Whoever is in the room when the land bank is formed will have a huge impact on how it will look and operate.” Poloncarz told Dave Debo of WBEN in April that most of the members were selected from those who have already been working on the land bank in recent months, and he will be drawing on the expertise of Whyte and LISC. Land bank board meetings will be open to the public, Whyte told me.

The land bank board will have 11 seats—five members from the City of Buffalo, three from Erie County, one each from the smaller cities, and one representing the Western New York Regional Council, overseen by Empire State Development. Here is the initial makeup of the board of the Buffalo Erie Niagara Land Improvement Corporation:

■ Brendan Mehaffy, Executive Director of Strategic Planning, City of Buffalo

■ Timothy Ball, Corporation Counsel, City of Buffalo

■ James Comerford, Jr., Commissioner of Permit and Inspection Services, City of Buffalo

■ Janet Penska, Commissioner of Administration, Finance, Policy, and Urban Affairs, City of Buffalo

■ David Comerford, General Manager, Buffalo Sewer Authority

■ Maria Whyte, Commissioner of Environment and Planning, Erie County

■ Joseph Maciejewski, Director, Real Property Tax Services, Erie County

■ Michael Siragusa, Erie County Attorney

■ Frank Krakowski, Lackawanna City Assessor

■ Joseph Hogenkamp, Tonawanda City Treasurer

■ Christina Orsi, Western New York Regional Director, Empire State Development

All three of Erie County’s cities have signed on, with Erie County, to jointly operate and oversee the land bank, which will be known as the Buffalo Erie Niagara Land Improvement Corporation. Almost certainly Niagara Falls will join shortly, as well, making this a truly regional land bank. Inner-ring suburbs like Cheektowaga—grappling with vacancies especially on the Buffalo line—are firmly on board, as are villages such as Angola. Cheektowaga Supervisor Mary Holtz and Angola Mayor Howard “Hub” Frawley have been advocating through the Association of Erie County Governments for years for a land bank, and both spoke at the Rath Building press conference announcing the joint application.

To drive home the extent of the problem countywide, at the press conference officials distributed a map of tax-delinquent properties around the county—more than 70,000 properties, representing $50 million in value. The illustration is essentially a disease map of blight, its little red dots showing a progression from the freckle-faced Southtowns, to outer-ring suburbs afflicted with persistent acne, to inner-ring rosacea exemplified by Cheektowaga, to the port-wine-stained cities. This is a problem of the extent, intricacy, and intractability with which no individual municipal government in the built-up areas is really equipped to cope—both in terms of policy and resources. The fact that of 44 individual government units in the county, most endorsed the land bank even though most will not be directly represented on its 11-member board, shows they understand that they need help grappling with this.

At the time of its announcement in March, approval of the joint application by New York State was almost a foregone conclusion (with approval formally received in mid-May), and not only because of Albany’s recent interest in providing Western New York effective tools and adequate resources to meet its many challenges. Sam Hoyt, now the biggest player in this part of the state at Empire State Development, the agency giving the land bank its seal of approval, was also the statewide legislation’s chief architect in the Assembly. And the state legislation allowing municipalities to create land banks was extensively modified to meet the needs of Buffalo—a 2008 version having been vetoed by Governor David Paterson due to the concerns of Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown. Most agree that the legislation passed last year was only improved by the delay.

“I worked for over five years to establish a land bank law in New York State,” Hoyt told me. “Now Dan Kildee, who was an invaluable partner in the creation of the law, describes the New York law as the gold standard for the nation. To see my home county and so many others apply to be designated as one of ten land banks in the state certainly is extremely gratifying.”

Shrinkage Problems

The land bank will provide tools to help grapple with the built-environment consequences of population shrinkage and demographic shift. But, in embracing it, will urbanized areas of Western New York finally be able to openly embrace the reality that we are shrinking?

Despite a few decades of efforts to halt the tailspin in urban quality of life, disinvestment, and population loss which seem to follow each other in a self-reinforcing cycle, Great Lakes and Rust Belt cities have had minimal success halting, let alone reversing, shrinkage. Although Buffalo is no exception, as recently as 2008 the city administration was expressing confidence that population loss would halt and turn around. From the Buffalo News (July 8, 2008): “The Mayor’s call for reform comes with the expectation that Buffalo will soon turn things around and start to grow its population again.” But the 2010 Census numbers doused that expectation with cold water. In fact, it appears the main factor even slowing Buffalo’s population loss is the influx of refugee settlement.

But that won’t help Buffalo’s inner-ring suburbs, originally settled by the post-war urban outmigration—a population overwhelmingly white and increasingly elderly. “It’s going to be tough to stop the decline in population,” said Poloncarz. “It’s demographics: More people are dying. We need to get more people moving in.”

Even cities that boosters point to as examples of urban turnaround, like Cleveland and Pittsburgh, continue to lose population. What many of these places also have in common (with some rare exceptions like Youngstown, Ohio) is shrinkage denial in both word and deed. This leads to an odd dance by city leaders and urban theorists who want to sell their communities and solutions without coming off as a Debbie Down(size)er.

And its not just an issue of the talk you talk, but also the walk you walk. Embracing shrinkage means facing some tough choices. In Youngstown, for example, shutting down city services to blighted and largely vacant blocks. Such moves, while seeming obviously necessary, can prove viscerally unpopular to implement. Per Michael Clarke of LISC, it comes down to a question of, “Who wants to be the one to tell a Polish grandmother on the East Side, who’s lived in the same house for decades, that she has to move because the city will no longer provide water and snow removal on her block?”

And in talking the talk? “Shrinking cities” is not a very sexy moniker. What else has been used? “Weak-market cities” was once popular among think-tankers. The Brooking Institution’s Bruce Katz, who is now a key figure in the Cuomo administration’s regional council process, told attendees some time ago at a conference that the terminology was “not selling.” Others have used “older industrial cities” (would you answer a personal ad from an “older industrial city”?) and more recently, “legacy cities.”

Dan Kildee prefers “high-upside cities.” Perhaps that’s why he’s currently doing so well in his run for Congress.

The land banker and land banking

Dan Kildee is the nation’s chief land bank evangelist, and a key to understanding a concept that can seem counterintuitive on the face of it—and should not be confused with land trusts (which protect land for conservation purposes), or even the longstanding vacant-properties strategy of holding contiguous vacant lots for future development.

Now running for Congress in Michigan, Kildee is co-founder of the Center for Community Progress, and during his tenure as treasurer of Genesee County—the Michigan one, home to Flint of Michael Moore fame—he was the founder of the test-bed Genesee County land bank.

Kildee was in Buffalo last October to talk land banks at the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s annual conference. At the conference, the banter between the two men (“Dan is the grandfather of land banks, and looks it,” said Hoyt) showed how closely and for how long they have worked together on the issue.

According to Kildee, the purpose of a land bank is not just to create a new entity that is a repository for vacant and abandoned properties but actually a way to remediate those properties. “[It is] a new pathway for the most distressed properties in your community to get them back into ownership—responsible ownership,” he said in October.

A land bank, in many ways, is the antithesis of the traditional tax foreclosure sale of properties on the metaphorical courthouse steps. Tax foreclosure sales to the highest bidder come in for a fair amount of heat from Kildee, especially when they’re held, as in many communities, online with bidding from out-of-town speculators (no longer allowed in the City of Buffalo).

Kildee sees the foreclosure sales, “based on transactional value,” as one of many policy holdovers from old ways of doing business that made sense before many of our communities became riddled with abandonment. Land banks, according to Kildee, “allow you to make decisions consistent with your values and ambitions for your community.”

Among values and ambitions operating in Buffalo, one clearly is preservation. At the preservation conference Kildee showed examples from Flint where the objective economic value of rehabbing a historic or architecturally significant building was far exceeded by its subjective value to a challenged downtown or neighborhood. Investing accordingly has led to revitalization on both small and large scales. And Jay DiLorenzo, head of the Preservation League of New York State described land banks as a perfect complement to New York’s preservation tax credit program—co-sponsored by the same legislators who co-sponsored the land bank legislation. The program, according to DiLorenzo, is an “incentive for reinvestment in historic downtown cores and historic neighborhoods—and especially historic properties in distressed Census tracts.” These are the same areas likely to be targeted by land banks.

But if land banks result in some properties not being sold to the highest bidder at foreclosure sales, won’t that result in local governments losing money? Quite the contrary, according to Kildee. As we all know in Buffalo, foreclosure sales, in many cases, just result in churn. New owners, even if not from out of town, can fail to get financing to make improvements, or get cold feet after realizing the amount of work involved or seeing the neighborhood. Then it’s back to the auction block again—often after a cycle of housing court actions, code enforcement efforts, decay, rodent infestations, crime, and even arson. All these things cost taxpayers.

In fact, Kildee considers speculation in distressed properties to be an outright socialization of risk, and privatization of reward. And in that sense, land banks represent as much a social movement as innovation in governance. “Now, the interest of the community—not the highest bidder—dictates what is done with these vacant properties,” Kildee told the Buffalo News in 2008. At the preservation conference, he went even further, saying that holding auctions for distressed properties treats them like “surplus rusty wrenches.” A key to managing the problem, he said, is to treat the properties more like what they are (and here’s a radical idea): real estate. “How many of you sell a house with an auctioneer?” Kildee asked the audience at the preservation conference. “If you treat property more like real estate, purchasers do, too.”

Common land bank misconceptions

■ The land bank will own and/or manage all the vacant properties in its territory. No: Land banks have limited resources therefore must be very strategic about where and when to get involved with a property; also, they must operate according to the strategic plans of each community where they operate.

■ The land bank is like a land trust. No: Land trusts hold generally large acreages for conservation purposes, generally do not acquire buildings, and do not have the same statutory tools for dealing with foreclosed properties.

■ The land bank will take over property demolitions from Buffalo. No: The land bank is not set up to get involved in providing services already provided by the municipalities where it operates.

■ The land bank will make money for Erie County. No: As a not-for-profit corporation under New York State law, any money the land bank makes will be put back into operations of the land bank. One of the goals of the state law is that land banks in New York become self-sustaining.

■ This will be another repeat of the MBBA debacle. No: The land bank legislation is not related to the miguided combination of legislation and complicated debt transaction that spawned MBBA.

■ The land bank will drive our vacant properties policy. No: As Michael Clarke of LISC told me, based on the New York State legislation, and fortified in the local application submitted, the land bank “only works within the strategic plan for the municipality. The land bank is not going to be the driver of policy.”

■ The banks will resist the actions of the land bank. No: According to Mark Poloncarz, many banks have been hoping the county establishes a land bank. Banks are notoriously bad residential property managers, and recognize that land banks have relevant tools at their disposal.

(Adapted partly from “Dispelling Common Misconceptions About the Genesee County [Michigan] Land Bank.”)

Writing for the Huffington Post in March, Kildee cites a study by the Federal Reserve of Cleveland of foreclosed property sales in Cuyahoga County (home county of Cleveland and several other communities with vacant property problems) that showed double the rate of continued vacancy in properties purchased by investors and speculators vs. individuals. Even more distressing, according to Kildee, “is the fact that while the delinquent taxes on properties bought by individuals almost always get paid, professional ‘flippers’ resolved tax delinquency on only 13% of their properties—extending the period of time in which government loses revenue and houses stand vacant.”

Making the sausage

Bringing land banking to New York State was a half-decade struggle. After several iterations, a 2008 bill passed the state legislature but was vetoed by Governor Paterson. By some accounts, the veto was requested by the Brown administration, which was reluctant to see land banks under county control as constituted under that bill; perhaps it was also a symptom of the rivalry between Brown and Hoyt, the bill’s principal champion in the Assembly. Others argue that the bill passed in 2008 was actually the worst of several previous versions, and that a major flaw was making each land bank a subsidiary of Empire State Development Corporation. (How well would that work out, given that another subsidiary of ESDC demolished a prominent vacant property for the Bass Pro project on the waterfront, leaving us with a hole in the ground, and later conveyed another prominent vacant property under its control in a sweetheart deal to a developer who was a boyhood chum of its board chair? What could go wrong?)

The current effort had to await the bottoming-out and recovery of both the economy and state politics. Under the 2011 law, land banks are constituted not as subsidiaries of any state agency, or even as state authorities (“I understand you don’t like the word ‘authorities’ in New York,” Dan Kildee told a Capital region audience to laughter last fall), but are intergovernmental entities—C-type corporations, constituted under the new Article 16 of the state’s not-for-profit laws. Western New York’s ESDC-managed regional economic development council will have a seat on the corporation’s board.

“This demonstrates for me the first time our local leadership is really getting serious about addressing regional problems on a regional level,” said Maria Whyte, Erie County’s commissioner for planning and the environment. “It’s important, because the vacant properties problem can’t just be a footnote in someone’s economic development plan. It’s one of our most pressing issues. In other words, we can’t just say we’ll bring in 20,000 new jobs and 20,000 new residents and that will take care of the problem. I said this to Chris Collins over and over, to no result.”

But this is a new and substantially different county administration; securing the joint, regional land bank shows just how much has changed since 2009, for example, when efforts to create a countywide planning board went down in flames.

Top 10 benefits of the land bank

■ One-stop shop: A land bank places all the tools to deal with distressed properties in one place—a one-stop shop for tackling vacancy and blight

■ Tax revenue: Since land banks can speed up the process for converting vacant, abandoned, and foreclosed properties to productive uses, the local government will experience an increase in property tax revenue generated by those parcels.

■ Cost saving: Local governments are able to reduce costs associated with added police services, emergency protection, inspections, etc. now required in blighted neighborhoods.

■ Maintenance: Provides maintenance services for vacant lots and abandoned properties.

■ Demolition: Able to undertake selective demolition of structures that are in serious disrepair.

■ Funding: Able to obtain outside financial resources to further its goals and supplement the revenue it receives through day-to-day operations.

■ Parcel assembly: The land bank can assemble and hold parcels that are in close proximity to one another for future transfer to a developer for housing, retail, and other purposes.

■ Liability: By transferring problem properties to the land bank, local government would no longer be liable for claims brought against them by entities that may have been damaged as a result of their exposure to vacant and abandoned properties.

■ Speed: A land bank can shorten existing foreclosure processes and speed up the return of vacant, abandoned, and tax delinquent properties to productive use.

■ Affordable housing: Affordable housing opportunities can be created through the land disposition policies of a land bank. Priority in the conveyance of property can be given to non-profit community organizations willing to construct or rehab the abandoned parcel for the benefit of low-income families.

(From Erie County.)

Still, by all accounts it wasn’t easy, with issues of control being central, including a lot of back and forth on the number of city representatives on the board. On at least two occasions (three, by some accounts) Poloncarz visited Brown at City Hall to keep the effort alive. In the end, a key factor in tipping the balance in favor of a joint, regional land bank were the state’s clear interest in regional approaches. (At the preservation conference in Buffalo last fall, Hoyt, while urging action on a local land bank, said the worst possible outcome would be a Buffalo land bank, a Cheektowaga land bank, a Lackawanna land bank, a Tonawanda land bank, etc.) Another important factor was the unexpected request of Niagara Falls Mayor Paul Dyster to be included. While the application submitted to the state doesn’t include Niagara Falls, the land bank’s name does include “Niagara.”

Whyte herself credits the land bank working group’s “intensity and discipline,” while noting that it built on the application already being developed by the City of Buffalo independently (because the Collins administration had shown no interest). Reading from her files, Whyte told me that between February 14 and March 23 alone, the group held 11 meetings, attended a national presentation Kildee, attended two statewide conferences and three legislative hearings, and made two presentations to the Association of Erie County Governments. And Whyte also credited the groundwork they had to build on, laid with “consistent community advocacy” by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), the Western New York Law Center, and leaders in all levels of local government.

What’s next for the land bank?

The first actions of the land bank with respect to real property are likely to happen around the city’s October in-rem property auction, according to Brendan Mehaffy, Buffalo’s director of strategic planning. Whyte suggested that, early on, the land bank is likely to look at properties that are challenged, yet part of a strong neighborhood or commercial district—the idea being to showcase the effort by making a notable difference, and perhaps even recoup some funds for future activities.

The first year budget will be around a million dollars, according to Whyte, some of which will come from a leftover “gift” from the Collins administration. Seed funding will include a $100,000 distressed properties fund proposed by then-Legislator Whyte and passed by the legislature over Collins’s veto, and then never spent by Collins. The land bank will look to recoup about $250,000 from the sale of properties, and hopes to snag at least that much in state and federal grants. For the balance, they will be seeking foundation funding and the value of in-kind services (inspections, etc.) provided by local governments.

More Reading

■ Certificate of Incorporation of Buffalo Erie Niagara Land Improvement Corporation. (PDF)

■ By-Laws of Buffalo Erie Niagara Land Improvement Corporation. (PDF)

Mehaffy pointed out that although the city is embracing the land bank, the land bank’s activities in Buffalo should be seen as enhancing what the city is already doing to combat the vacant property problem. “When we showed the county what we were already doing, they were impressed,” Mehaffy said. Over a couple of decades Buffalo has learned much of what works and doesn’t the hard way, from sources such as the anti-flipping task force, the MBBA debacle, and the empirical lessons of Judge Hank Nowak’s housing court. Related developments Mehaffy listed include an upgrade to Buffalo’s somewhat infamous property management software system, Hansen, which he said “should address a lot of longstanding issues,” and Buffalo Green Code, the continuing effort to reconceive the city’s zoning and land use regulations.

I asked Michael Clarke of LISC if he sees the land bank ever operating in a redevelopment capacity, undertaking strategic projects along the lines of the PUSH Massachusetts Avenue projects that were managed by Sean Ryan before his election to the Assembly. Clarke sees that as conceivable, but likely down the road. Much of the land bank’s initial work will be as a facilitator, tackling some “low-hanging fruit” such as cleaning up the title on a problem property on a block so it can be resold, and leveraging existing relationships and in-kind services with municipalities. Also, working with nonprofits such as Belmont, which already do rehab work in some inner-ring suburbs.

Over time, the land bank will be able to grow and respond to conditions as necessary. By virtue of operating county-wide, it should be able to use proceeds from processing more marketable foreclosed properties in some areas, to cover costs of handling more marginal properties in more challenged areas.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n24 (Week of Thursday, June 14) > Like Money in the (Land) Bank This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue