Next story: Time Out of Time

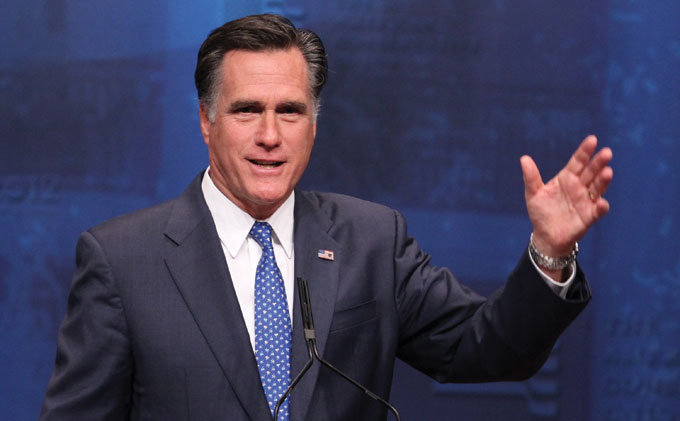

The Real Reason Romney May Win in 2012

by Bruce Fisher

After the crash of 1929, FDR used the scandalous revelations of the Pecora hearings to pursue a transformative agenda. What has Obama done?

The moral clarity that the Occupy movement provided in 2011 was gone by early 2012, as the inherent elitism of the people who filter our news reasserted itself. The newspaper editor who drives a smart German car, the TV anchor who has a stock portfolio that is inching toward seven figures, the business news columnist who gets taken to lunch at a ponderous downtown club where the lobster bisque is creamy—these are the psyches that, like our president’s, can’t quite get comfortable with the idea that there is an unbridgeable gap between striving, prosperous people like themselves and the reborn American plutocracy of financial speculators.

The scruffy unemployed sign-holders are gone from the parks and downtown squares of American cities, where for many months last year they attracted media attention to the new realities of income distribution in America. At least since 1985, Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz and Bob McIntyre’s Citizens for Tax Justice and former Washington Post reporter Tom Edsall have been warning about the consequences of the richest one percent gobbling up ever greater shares of total personal income. Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez’s new analysis of tax returns since 2008 shows that more than half of all the new income produced since the financial crash of George Bush’s last year in office has gone to just 15,000 of America’s more than 100 million households. Those 15,000 households can’t possibly buy enough cars, houses, toys, clothes, and other consumer items to stimulate our consumption-driven economy. But since they are taking so very much of the available income, leaving so little for everybody else, that leaves everybody else consuming only what they can borrow to consume.

It’s a slow-simmering crisis in an election year. Confusion about the crisis abounds, and memories of the 2008 financial crisis are fading. Frustration with a slow economic recovery is so widespread now that Mitt Romney is a plausible president despite his offshore bank accounts, his wife’s plural Cadillacs and plural nannies, and his celebration of automated checkouts at retail stores that sell only Chinese-made merchandise in a capitalist’s dream, which is now our new reality, the reality that excludes American workers at every stage of the process except paying the price.

The acute awareness of crisis peaked last year in a bunch of city parks, and then it ended. The narrative of rich and poor, of good and evil, of justice and injustice, and of right and wrong as permanently juxtaposed opposites has once again gone all squishy.

Barack Obama struggles for a narrative. Congressional Democrats lack a simple moral tale. If only we had our own version of the Pecora hearings.

Telling the story

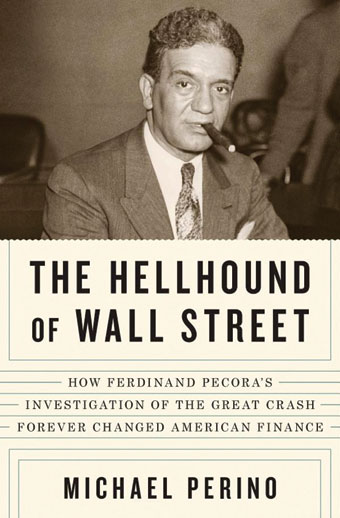

In the last few days of Herbert Hoover’s presidency, an up-from-nothing Italian-American lawyer named Ferdinand Pecora, working for a Norwegian-American member of the US Senate named Peter Norbeck, exposed how self-dealing, larcenous Wall Street investment bankers caused the stock market crash of 1929 that kicked off the Great Depression. In barely a week of hearings, Pecora made the complex issues of financial market manipulation, insider trading, false dealing, and profiteering simple—so simple, in fact, that it’s no exaggeration to say that all of the legislation that reined in Wall Street’s excesses, from the Glass-Steagall Act to the various truth-in-investing laws Congress passed, were only possible because of the show Pecora put on.

Pecora’s story is very capably told in Michael Perino’s book The Hellhound of Wall Street. It’s one of those books that uses the transcripts of what was essentially a courtroom drama, puts the testimony of all those witnesses in context, and charts the day-by-day media reactions and the real-world events alike, and withal tells a story that we should be re-living today.

The parallels with recent history are horrifying, but so are the differences. We have no heroic Republican senators with both business credentials and a sense of moral clarity today to do what progressive Republicans (now an oxymoron) did then. We have no tough ex-prosecutor like Pecora brought in at a cheap wage, with no prospect of a big-dollar payoff afterward, being turned loose on the guys who brought the house down.

We do have Bernie Sanders in the Senate and Marcy Kaptur in the House, but nobody with the stature of a James Couzens, the Republican senator from Michigan who stood guard, as an industrialist, against the bankers of the Roaring ’20s, the ones whose counterparts in the past decade castrated all regulators, corrupted the formerly independent rating agencies, then peddled concocted securities based on worthless mortgages for which, when their worthlessness was exposed, the American taxpayer paid.

We today have no aristocratic presence like Senator Couzens. Car-manufacturing pioneer Henry Ford gets all the credit for having raised factory workers’ wages high enough so that they could actually afford Fords; the credit instead belongs to his ex-partner Couzens, who made his millions and then moved on. “I want,” he said, in explaining why he wanted to be in the US Senate, “to do what I can to see that life is not made a burden for the many and a holiday for the few. I want to do that which will contribute the greatest good to the greatest number.” How faraway seem the days when a powerful elected official would unabashedly make such a statement and be taken seriously.

What Pecora did was to create a galvanizing drama that shaped public opinion at a time of national economic crisis. The Senate had bungled the public education process for three years, as had President Herbert Hoover, who had been elected in part because of his reputation (reminiscent of Romney’s Olympic reputation) as the engineer of Europe’s recovery from the devastations of World War I.

Hoover proved utterly inept, and everybody in the country knew it. Banks were failing right and left as Pecora pulled admission after damning admission out of his arrogant, swinish Wall Street witnesses. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was days from taking office while this went on; as the country awaited his inauguration, the pressure on him to deliver a transformative agenda was immense. Roosevelt and his team followed Pecora’s lead. With the help of the prosecutor, plus some senatorial noblesse oblige and some great speechwriting, they seized the moment.

The Obama difference

Obama and his attorney general Eric Holder and his speechwriter David Axelrod have all the tools at hand to prosecute the William Fulds, the Lloyd Blankfeins, or any of the other latter-day “Sunshine” Charlie Mitchells and the Richard Whitneys who scammed millions of investors before the Crash. Obama’s critics have characterized him as a self-satisfied Boomer surrounded by guys who still want a taste of the big money that can only be got from Wall Street, guys who see the example of Rahm Emmanuel, who made more than $15 million in the time between working for Bill Clinton’s White House and serving in Congress, and who helped raise tens of millions from Wall Street to help elect Democrats in 2006.

The current political economy seems to work as William Butler Yeats pegged politics in the 1920s: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity,” he wrote in “The Second Coming.” Lacking clarity, lacking a simple story of the 99 percent versus the one percent, lacking a narrative that can explain that what was terribly wrong in 2008 is still terribly wrong, we may yet get our own version of Herbert Hoover.

Bruce Fisher is director of the the Center for Economic and Policy Studies at Buffalo State College. His new book is Borderland: Essays from the US-Canada Divide, available at bookstores or at www.sunypress.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n25 (Week of Thursday, June 21) > The Real Reason Romney May Win in 2012 This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue