Next story: Joe Bajus Jr. at 464 Gallery

War of 1812 exhibits at Karpeles manuscript museum and the downtown library

by Jack Foran

Pabst and Perry

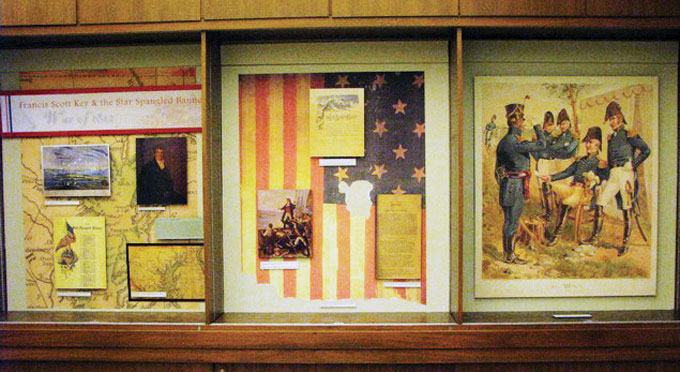

Feeling the need or desire to brush up on your War of 1812 lore in this bicentennial year? There are two exhibits up to help you do that, one at the downtown Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, one at the Karpeles Museum on Porter Avenue.

The library exhibit includes a short video that provides an overview big picture of the war. The American-British war was a sideshow in the European Napoleonic Wars, which were mainly between Britain and France. There was no real winner in the War of 1812, except that the United States—though the adjective “united” in the formulation was still a little strange-sounding and, as ever, seriously problematic—reestablished for good its independence from Britain, but one decided loser, the American Indians, who fought on the side of the British, partly in deference to their traditional alliance going back to the Revolutionary War, but generally in consideration of the Indians’ understanding that the Americans’ long-term objective was continued migration west, pushing the Indians further and further west, ultimately to make them disappear.

A lot in the library exhibit on the burning of the villages of first Black Rock and then Buffalo on December 30, 1813, in retaliation for the Americans’ invasion of Canada and burning of the Village of Newark—now Niagara-on-the-Lake—earlier that month, which in turn was retaliation for the British invasion and attack on Black Rock on July 11, 1813. The library exhibit includes an original letter by one James Sloan, an itinerant merchant in Black Rock at the time and partial eye-witness of the attack, who tried to sleep through it all, but kept getting roused out of his rest by importunate soldiers and the general rumpus and commotion.

Another letter relates of a surprise attack by Indians on an American force of some 30 men, 17 of whom were slaughtered. The letter says that the victims “were mangeled and scalped in a manner not possible to be discribed, and three of them cutt open and their hearts taken out, and one with his penis and testicles cutt off.”

Much also on Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and the famous Battle of Lake Erie, in which Perry, under a banner proclaiming “Don’t Give Up the Ship,” initially and ironically abandons his ship after it is disabled and most of the crew dead, and rows to and takes command of another ship in his armada that had been fighting ineffectively because from too great a distance from the heavy action, and deploying in close, skillfully and valiantly, delivers knockout cannon fire to the enemy.

Among the Perry items on display, a broadside ballad proclaiming: “Columbian tars are the true sons of Mars,/They rake fore and aft when they fight on the deep,/On the bed of Lake Erie commanded by Perry,/they caused many Britons to take their last sleep.”

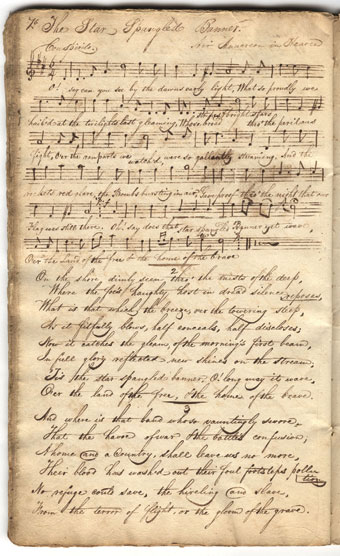

The Karpeles exhibit features a series of documents, many of them handwritten by the likes of the president during the war, James Madison, and his secretary of state (and later president), James Monroe—politicians at the time not only composed their own letters and official documents but transcribed them—on a variety of relevant topics such as diplomatic efforts to curtail or end some of the root causes of the war, such as British impressment of American merchant seamen who may or may not have previously left Britain and/or the British navy to avoid war service. In the diplomatic initiative that came closest to resolving the problem, Britain would have terminated the impressments if America agreed to terminate its Non-Intercourse Act, which sounds like a non-starter anyway, and was said to be unenforceable. Though it wasn’t what it sounds like. The Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 decreed embargoes on American shipping to British and French ports.

The Karpeles documents encompass the period before, during, and after the war. A letter from London, where he was employed on a diplomatic mission, by future President John Quincy Adams after the conclusion of the American-British war and the world war, reveals with copious metaphor his dire outlook for a long-lasting European peace and the source he saw of further menace: “In shaking off the fetters of a French military despotism, Europe is passively submitting to be re-shackled with the manacles of feudal and papal tyranny. She has burst asunder the adamantine chains of Buonaparte to be pinioned by the rags and tatters of Mockery and Popery. She has cast up the Code of Napoleon, and returned to her own vomit of Jesuits, Inquisitions, and Legitimacy, or Divine Right.”

Another document is a war hero proclamation for Commodore Perry signed by President George Washington, who had died in 1799. Accompanying explanatory material says that Washington had signed two such proclamations, left blank, to be filled in eventually with the names of future heroes. The other one went to Stephen Decatur, another naval notable of the era.

One of the library exhibit items is a late-19th-century advertising poster which strains to somehow connect the supposed energizing effect of the quaffing of Pabst beer on a hot summer day and the heroic actions of Commodore Perry during the Battle of Lake Erie. Under a handsome illustration of Perry in the little rowboat proceeding to his second ship, the Pabst promotional copy reads in part: “The human body in the heat of summer may be likened to a ship in a dead calm; she cannot make port without the little tug boat, which catching her by her loose cable, pulls gently but gradually, and taking up the slack, brings her safely to dock.

“The nerves, the muscles, and the mind in summer are at the slack of their cables…”

blog comments powered by Disqus

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n30 (week of Thursday, July 26) > Art Scene > War of 1812 exhibits at Karpeles manuscript museum and the downtown library This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue