A Comedy for Some and a Drama for Others

by Nikolai Evreinov

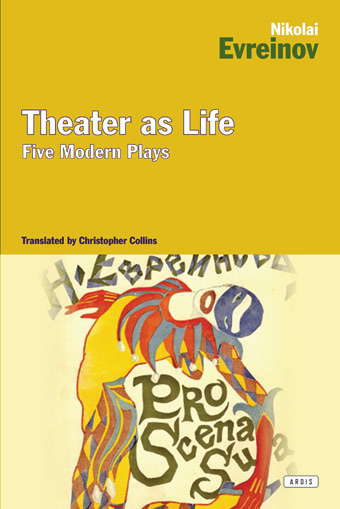

Theater as Life: Five Modern Plays

by Nikolai Evreinov (translated by Christopher Collins)

Ardis Publishers, 2012

One of the most attractive things about Russian literature is that it is generally, for lack of a better word, nuts.

Actually, let’s come up with some better words: absurd, frenetic, bizarre, a rotating kaleidoscope of pathos, philosophy, and humor. Needless to say this is not true of every Russian writer, but it is certainly the case with those I like the most. I’m thinking here of Gogol, Dostoevsky, Nabokov, Erofeev, Bulgakov, and Olesha. There is in the work of these authors an ineffable wide-eyed hilarity that critics and students have noted with increasing frequency since the advent of Gorbachev’s glasnost and the subsequent loosening of the floodgates that would prove fatal to the Soviet Union. Western critics sometimes like to attribute these qualities to a psychology that pervades all of Russia (a nation which itself spans nine time zones). A review in Footlight and Lamplight of Nikolai Evreinov’s play The Main Thing (also translated as The Chief Thing) observed that “the Russian mind prefers to treat a fantastic theme like this with a strange blend of fantasy, burlesque, and seriousness.” Whether or not this is true of the Russian Mind, it is true of Evreinov, and it is beautiful.

As I see it, the frank and frantic blend of humor and poignancy in Russian prose is achieved primarily with a unique narrative technique called skaz (сказ). This term refers to a form of storytelling (skaz comes from the word skazat, “to tell”) that uses slang and a noticeably familiar tone. The voice also occasionally references the community or speaks of a decidedly un-royal “we,” e.g. “Most of us townsfolk found his actions reprehensible, although several of us with more voluptuous temperaments disagreed.” Skaz is most striking when it is used in a third-person omniscient narrative, however. Like free indirect discourse, it contaminates an otherwise sterile perspective and inflects it in a more familiar way, as if the narrator is not simply a device but a friend who is telling you a story. The first line of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov demonstrates all of this: “Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov was the third son of a landowner from our district, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, well known in his own day (and still remembered among us) because of his dark and tragic death, which happened exactly thirteen years ago and which I will speak of in its proper place.”

All five of the plays collected in Theater as Life, a concise, well translated sample of the work of Nikolai Evreinov (1879-1953), show the marks of the influence of skaz prose. The three plays that end the collection, The Main Thing (1920), The Ship of the Righteous (1924), and The Unmasked Ball (The Theater of Eternal War) (1928), feature so many characters that the dramatis personæ becomes the collective personification of the community a skaz narrator references. The first two, A Merry Death (1908) and The Theater of the Soul (1912), begin with extended monologues addressed to the audience. These are marked in their familiarity: “Shh…Quiet! Take your seats as noiselessly as possible and try to keep any talking and shifting in your chairs to a minimum…” Evreinov “breaks the fourth wall” like this often in his work. Each time it arrests the drama and forces the audience to recognize the play as a construction, as theater, and, most importantly for Evreinov, as a necessary lie.

Evreinov’s plays combine a theoretical interest in theater with a philosophical obsession with life as a staged drama and a deep, sincere human empathy. The result is a polyphonic mélange of set pieces “that seemed to have been painted with poison,” plays-within-plays-within-plays, stock characters of commedia dell’arte that recognize their own unchangeable roles, biting criticism of the contemporary Russian sociopolitical order, and love.

Consider, for instance, the second play in the book, The Theater of the Soul. It is what Evreinov called a monodrama, which Collins defines as “a dramatic representation in which there is one central figure, and in which the central figure himself, the other characters, the set, the action are not to be considered as representing some objective reality, but as representing the central figure’s varying subjective perceptions of himself and the world around him.” The stage is set with two giant green lungs and an enormous heart at the center, with musical strings representing nerves in front. The three characters are S1 (the rational self), S2 (the emotional self), and S3 (the subconscious self). The man they comprise is a drunk with a wife and children who is smitten with a lounge singer. As S1 and S2 argue over what the man should do, the lungs and heart inflate more quickly or more slowly in accordance with the timbre of the action onstage. The man, overcome by his indecision, shoots himself in the chest and bright red ribbons stream out of the massive, no longer beating heart.

The best play in Theater as Life, The Main Thing, provided Evreinov with lasting international success, but more importantly it is his most triumphant expression of the themes that occupy his work. Its political message is complex enough that it prompted audience members to denounce him as both a Bolshevik agent and a critic of the Soviet government. It is stunningly modern and Gordian, which in turn makes it, to put it lightly, difficult. This polarized critics across the world, excepting of course the Americans, who generally found the play’s modernism and relativism abstruse and indulgent. The same astute critic who commented above on the Russian mind wrote of The Main Thing, “When the author deliberately cuts his play short by telling you in so many words that you could finish the story according to your own taste, he accomplished at one stroke the winning of an enthusiastic audience in Europe and the losing of all save a few dramatic connoisseurs in this country.”

The play’s first act takes place in a fortune-teller’s hovel. Immediately, no fewer than five characters appear, one after the other, each with his or her own complex story and insoluble problem. These individual dramas are difficult to follow, but the main thing is that each character is connected several others in ways they cannot yet anticipate. At the end of the act the fortune-teller disrobes to reveal that she is a man named Dr. Fregoli, a character that is in fact but another disguise for Paraclete, the personification of advocacy and counsel and the less greedy Russian iteration of Jonson’s Volpone. He will use the fortunes he has dispensed to his stricken customers to orchestrate their denouement. In order to achieve this, in the second act he visits the rehearsal of a production of Quo Vadis to hire actors to infiltrate the boarding house where the troubled fortune-seekers live. Much of this act is spent on the hilarious and fraught rehearsal of the clearly doomed production. As the third act begins, the actors have all positioned themselves nicely in relation to the ostensible subjects of Dr. Fregoli’s intervention. The remainder of the play examines the questions that arise from each actor’s act of double-agency, questions that clearly preoccupied Evreinov’s theoretical concerns: Is truth always the greatest good? Does truth necessarily mean the absence of artifice? Is it bad to lie? And if so, “what of it? And do you suppose speaking the plain truth in public is such a good idea?” The playwright plays with these issues relentlessly. Evreinov literalizes his belief that no existence is totally true to itself, that no person is entirely consistent, by having each character reveal a secret motive or don a mask or costume. The resultant play, while at times confusing, portrays in all its myriad falsity a clearly unreal but at the same time deeply real life.

And then of course the ending. Evreinov utterly demolishes the spellbound audience’s involvement in the story by laying bare the artifice of the whole thing, of everything, (and that is of course “the main thing”). The director of the production of Quo Vadis walks onstage and says to Harlequin, who has been asking frantically what each audience member’s preferred ending might be, “The main thing is finish the play on time. The hour is late, the audience is anxious to get home, lots of them have to go to work early tomorrow!” Whereupon the regisseur approaches and says, “The main thing is to have a smash ending for the play. Everybody dance! A burst of laughter! Something like that!…Throw confetti! More life! Audacity! Merriment! Youthfulness! Cur-tain!”

I have never read anything like the plays collected in Theater as Life. They are stunning, mesmerizing works that examine a wide range of philosophical and moral questions while remaining fundamentally human dramas. Christopher Collins’s translations are fine indeed and (with only a few small exceptions) free of any sort of clunkiness. The translator’s introduction is particularly useful to the uninitiated, which category encompasses me and I’ll assume most people. Great. Read it!

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n34 (Week of Thursday, August 23) > A Comedy for Some and a Drama for Others This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue