How Good It Is To Be Us

by Woody Brown

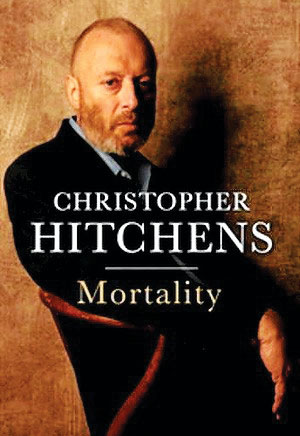

Mortality

by Christopher Hitchens

Twelve, September 4, 2012

Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011, at the height of his renown. His book God Is Not Great, released in 2007 and nominated for the National Book Award that same year, had vaulted him to a position of leadership in the New Atheism movement, along with the other three horsemen: Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and Richard Dawkins. In 2010, he published his memoir, Hitch-22, which critics met with widespread acclaim. His spirited endorsement of the Iraq War, his case for which he made in his 2003 collection of essays, A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq, had pretty much faded out of the public consciousness and the liberal establishment fell back in love with the razor-sharp vitriol he used to express the logical conclusion of his antitotalitarian crusade: antitheism.

Antitheism, not atheism, because while the word “atheist” connotes nonbelief in God, it does not signify the other, louder characteristic of Hitchens’s personal life and career: namely, that he was a man the vast majority of whose intellectual occupation was the opposition of God, religion, and belief generally. He was impressively well-read and his prose style was clean, economical, and deeply funny, but he used his creative energy mostly to further an agenda that involved dropping on the ground the ice cream cones of rabbis, reverends, and imams alike. Though it is clear to anyone watching or reading that Hitchens throughout his career enjoyed demolishing the beliefs of as many people of faith at the same time as possible, the man himself never examined critically the jouissance he derived therewith.

But we all must believe in something, it seems, and what fills the role of what the Underground Man called “the most desirable good” in antitheist doctrine is God’s negative, the Absence of God. Consequently we see the fetishization of Science until it appears to be God-like (cf. the epidemic hyperprescription of psychotropic antidepressants, or the current sales slogan for Epiduo Gel, “Blame biology!” or also the impressive celebrity of figures like Neil deGrasse Tyson, Carl Sagan, and Michio Kaku) and the constitution of a deeply (almost sexually) gratifying militant antitheism in a mirror-image opposition to the servile ecstasy of missionary theists. So there is our Antitheist Trinity: God’s Absence (the Father), Science-as-God (the Son), and the unspeakable Jouissance of the Missionary (the Holy Ghost).

What I am saying here has nothing to do with the question of whether or not there is a God. That is a deeply uninteresting debate, boring chiefly because of its irresolvability, and yet it bogarts the entire theist/antitheist discourse. As a result, few prominent intellectuals whose celebrity matches that of juggernauts like Hitchens comment on the following worthy topics of discussion: antitheism as a social movement with its roots in the Enlightenment, antitheism and its relation to the symptomatic resurgence of fundamentalism in the United States (Slavoj Žižek has addressed this one), and antitheism as structurally identical to theism. Three dissertations waiting to be written, PhD students.

Voice From the Underground

Underground newspaper publisher Paul Krehbiel talks about Buffalo’s radical press in the 1970s

Paul Krehbiel’s first day working in the dismal environment of the Standard Mirror Company in South Buffalo in 1968 was also his first step toward founding the underground worker’s newspaper, New Age, in 1970. Krehbiel tells the story of that newspaper and its place in Buffalo’s progressive community in Voices from the Underground, a four-volume chronicle of the underrgound press edited by Ken Wachsberger.

Krehbiel long ago left Buffalo for the West Coast, but he returns this week to deliver three talks about New Age and the radical press in Buffalo:

Sunday, October 7, 4-6pm, at Riverside-Salem Church (3449 West River Road, Grand Island.

Monday, October 8, 7-8pm, at Talking Leaves (3158 Main Street, Buffalo)

Thursday, October 11, 7-9pm, at Burning Books (420 Connecticut Street, Buffalo).

Krehbiel will have copies of the book for sale. It is also available at www.voicesfromtheunderground.com.

If there is a problem I have with Mortality, it is Hitchens’s refusal to back down from his antitheist agenda. Now, clearly that is something that many if not most people will appreciate and laud as evidence of the strength of his constitution. And in fact, it is impressive. Hitchens was certainly not a wilting flower even when he was literally on his deathbed. And, to clarify, I don’t mean I wish he had suddenly become religious. It’s just that he seemed to be debating someone, trying to convince someone somewhere that God did not exist, up until the very moment he died. And the parts of the essays in Mortality that deal with that argument are far less compelling than the really impressive centerpiece: his unflinching examination of his own death.

“I am sixty-one. In whatever kind of a ‘race’ life may be, I have very abruptly become a finalist,” Hitchens writes, and that statement is a perfect example of the devastating economy of his prose style. His sentences seem to be the most perfect possible expressions of his thoughts—the reader cannot imagine them written a better way. This quality was certainly evident in his speech, a fact to which anyone who has ever heard him speak can attest. He dedicates an entire essay to a smart perusal of the relationship between speech and writing, occasionally musing on the unhappy fact that the cancer that would eventually metastasize and kill him was of the esophagus. And he addresses the spitfire claims of the fundamentalist internet that his fatal illness “was God’s revenge for him using his voice to blaspheme him [sic]” with another brief flick of the verbal switchblade: “If you maintain that god awards the appropriate cancers, you must also account for the numbers of infants who contract leukemia.” I am reminded of the words of Father Maxi from an episode of South Park: “It is then that we must understand God’s sense of humor is very different from our own. He does not laugh at the simple ‘man walks into a bar’ joke. No, God needs complex irony and subtle farcical twists that seem macabre to you and me. All that we can hope for is that God got his good laugh…”

Whatever one thinks about Hitchens, the following facts remain: 1. He was an intelligent, wise man who embraced with all available verve his passions for reading, writing, arguing, drinking, and smoking; 2. His exploration of his death is deft and moving; 3. The previous facts would remain true whether he had spent his life arguing for the existence of God or against it. Hitchens would probably disagree with the third one, but no matter—Mortality is a powerful, stirring collection, one that I would certainly recommend to anyone reading this.

Hitchens was an antitheist through and through, so much so that he even recognized the possibility that he would go over to the dark side in his last days. But ever true to himself, he left a snarky note to cover even this outfield base: “If I convert it’s because it’s better that a believer dies than that an atheist does.” Amen.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n40 (Week of Thursday, October 4) > How Good It Is To Be Us This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue