Innovative drawings at UB Art Gallery

by Jack Foran

Falling Through Space Drawn By the Line

The current UB Art Gallery show primarily of drawings pushes the envelope of that artistic category. Sometimes by processes so radically different from what we think of when we think of drawing, videos are needed to show how it’s done. Some by ordinary pencil and paper means, but work so meticulously rendered, you think it couldn’t be drawing, it must be photography. Some not made with pencil (or ink) and paper at all. One almost totally audience participation piece, and you don’t have to know how to draw to participate. (But do have to know how to read.)

One of the works with video is by Tony Orrico, whose whole-body drawing method is a little like that for making snow angels, but not on snow but an enormous paper canvas, and circles not angels, eight of them, in an overall octagon pattern, tending toward another overall circle. The eight circles evoke physics class explanations about atomic orbitals—electrons everywhere and nowhere at a given instant—or when you watch the video, which shows the work in the making, Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous Vitruvian Man drawing. It’s a mighty piece, the piece on paper, but the video also needs to be seen. Art doesn’t get more energetically gestural than this.

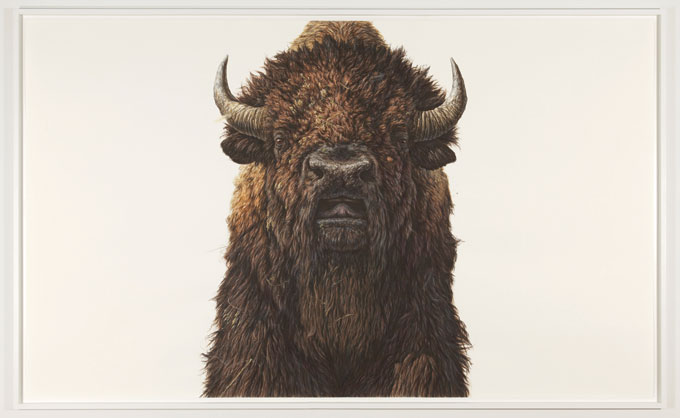

There are impressive drawings in the traditional, representational way. A life-size, face-on, up close and personal portrait of a bison—zoo bison, it looks like—precise in detail down to the straw morsels in the matted facial wool, and ambient flies, by George Boorujy. And a group of exquisite works by Charles Ritchie, including several postcard-size renderings—one of a living space interior, one of an outside wall and window looking in on possibly the same interior space—with no whit less of detail due to the small format. More, it seems. Another somewhat larger-format scene is of a person working at a desk, at night, the immediate work space in front of him brightly lit, the rest of the picture so dark by contrast that for a minute or so it appears undifferentiated black. Until gradually you see furniture, the rest of the room interior.

Two lovely understated feminist works by Ellen Lesperance started from video documentation of political demonstrations in which the artist observed a woman in a sweater in colors and patterns somehow—intentionally or by chance—reflecting the woman’s political ideology. The artist then developed, as well as possible based on the evidence of the video, a knitting pattern on paper, in grid squares, coloring in the squares to match the sweater design. The final product is a knitted sweater, along with the pattern on paper. Two examples are on display, one in vivid red and black horizontal stripes, a kind of desert Indian blanket motif, the other in a woodsy brownish green, with fir trees and an animal that might be a unicorn but is more likely an antelope.

Things fall apart, but also come together in Michelle Oosterbaan’s heady blend of figural imagery emerging from and dissolving back into an abstractionist matrix of shards of color spectra. Whereas Marsha Cottrell’s large digital and hand-drawn work evokes time-lapse photos of star paths across the night sky, and previously undetected funnels of swirl forms. Yeats’ gyres, perhaps. And next in line secret of the universe after string theory?

The other artworks with video to show how they were done are Rosemarie Fiore’s fireworks drawings, which were produced by setting off fireworks in an upside-down tin can that the artist, wearing insulated gloves and using a stick, then pushed across a paper, burning a carbon trail into the paper, and sometimes some of the fireworks colors.

The audience-interactive piece is by Molly Springfield, and to the extent that it is about drawing is about the pentimento, trial and error, nature and associations of that art method and practice, and then by extension, of all methods of learning, of discovery, as essentially trial and error, essentially process, and essentially participatory. All learning is active learning. The piece consists basically of a Xerox machine—but you could use any such machine—and a letter to the audience soliciting marked-up passages in a text they have read, revealing their interaction with the text, whether by way of argument or clarification in other words. The artist’s intention is to collect all submissions into a computer archive that viewers will be able to access and add to with further marginalia. Attached to the letter is a form on which the submitter is asked to provide some basic personal information and information on the marked-up text. In what context did you first read it? Etc. An earlier version of the letter is on display, featuring copious editing changes, cross-outs, improvements in wording.

Lots more art and artists. The curators of this excellent exhibit were Sandra Q. Firmin and Joan Linder. The show continues through December 8.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n42 (Week of Thursday, October 18) > Art Scene > Innovative drawings at UB Art Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue