The Silliest Damn War

by Mason Winfield

Oh! now the time has come, my boys, to cross the Yankee line,

We remember they were rebels once, and conquered John Burgoyne;

We’ll subdue those mighty Democrats, and pull their dwellings down,

And we’ll have the States inhabited with subjects to the crown.

—1812 War-era ballad, “The Noble Lads of Canada”

Dispatches: The War of 1812

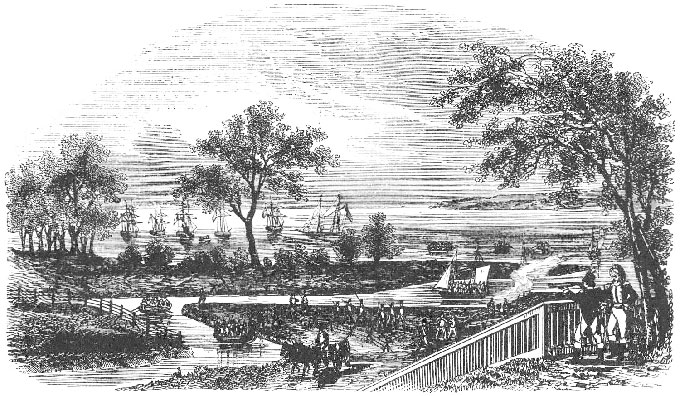

It was Indian summer in 1812. As if he looked to the Niagara as he wrote his ode, the poet Keats would memorialize the feeling of Western New York’s outrageous falls just a handful of years later. Still, but for the soldier camps, the newly declared war seemed a long way off to Western New York. Then people in Buffalo, Black Rock, Manchester (Niagara Falls), then Lewiston looked across the river to see that all had changed.

Escorted by strutting Redcoats, 400 Americans limped and groaned along the Portage Road, today’s Niagara Parkway in Ontario. Their general, William Hull, a Revolutionary War hero, was among them. Where the Niagara narrows, they were in sight and even sound of their fellow citizens, “marched like cattle from Fort Erie to Fort George…with all the parade and pomp of British insolence,” according to Peter Porter, quartermaster-general with US forces at Lewiston. Kept from doing anything about it by the mighty strait—a connector of bodies of water—that we persist in calling a river, Porter and all his comrades could only gnash their teeth, clash their swords, pound their gunstocks, and “look on and sicken at the sight.” This parade of POWs of the shabby surrender at Detroit was the Niagara’s welcome to the War of 1812. How had things gone so bad so fast? Why were we fighting, anyway?

Like most grudges, the 1812 quarrel had roots, some in the Revolution. While the Empire gave up fighting about American independence, it delayed handing over forts along the Great Lakes, like Forts Detroit, Oswego, and Niagara. (After all, the US hadn’t repaid Loyalists—in the US they were called traitors—for possessions lost when they fled to Canada.) It kept Revolutionary-era alliances with many Native American nations and encouraged attacks on American frontier settlements, which infuriated Representatives from new states in the South and West—the original “War Hawks”—were using to whip Congress into a foaming rage. Other causes were current. By 1812, England was at war with Napoleon. Its mighty navy blockaded France, which killed a lot of US trade and devastated our economy. Another irritation was the practice of impressment. As the British Navy intercepted American ships on the high seas, it took off sailors presumed to be British subjects. (In those days it wasn’t easy to tell Brits from Yanks by accent, and many Americans were hauled in.)

Used to its own snippy way of playing payback, the Empire was slow to see that the US was hitting the boiling point. Even history would be a little foggy on why this war was ever fought. Still, the British Parliament passed conciliatory measures only two days before President James Madison signed the declaration. (“This war would never have been fought,” wrote Louis Babcock, “had the telegraphic cable then been installed.”) The US couldn’t get at England, so attacking English interests it could reach—like Canada—seemed a good second-best. What President Harry Truman called “the silliest damn war we ever had” was underway.

While General William Hull’s only Niagara connection was marching along it as a POW in the fall of 1812, he was just one in a line of disastrous American commanders in the first half of the war.

Born in Connecticut, Hull fought with Washington’s army in eight major Revolutionary battles. A judge, a state senator, and the governor of the young state of Michigan, he was one of the few American leaders in 1812 with war experience. He also bore the signs of indulgence in food and drink. Surely sensing that his campaigning days were past, he declined his first commission in the 1812 war. When illness forced a predecessor to the sidelines, he took over the defense of the northwestern states. Hull was completely bamboozled when British Major-General Sir Isaac Brock showed up outside Fort Detroit and let on that he wasn’t up for a massacre, but that he couldn’t speak for his Native American allies unless somebody gave up quick. The portly senior should have been chortling over cards and playing Santa for his grandchildren, not penned in a fort and plagued with thoughts of death and torture. Contemporaries give us an image of the old hero crumbling, eyes wandering, stuffing wad after wad of chew into his splotchy chops, his outfit streaked by the coppery drool.

As he marched along the Niagara, Hull must have known that the worst was ahead. His abrupt give-up to a smaller force seemed even treasonous to many Americans, and Hull was tried, convicted, and spared being shot only by a presidential reprieve. He spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name. The son who marched beside him, Abraham Hull, would be marked by this contumely, too. He would have a far different fate on the Niagara, but it would take till the end of the war to meet it.

Mason Winfield is the author of 10 books, including Ghosts of 1812 (2009, Western New York Wares), the only recent history of the 1812 war on the Niagara.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n42 (Week of Thursday, October 18) > The Silliest Damn War This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue