Next story: Millions of Dollars in Contracts Flow Through Buffalo City Hall

WNY Economy 2.0?

by Bruce Fisher

Trying for a paradigm shift, again: The Western New York Regional Economic Development Council moves closer to a plan for the governor’s promised $1 billion.

When we think about regional economic development, we are ever-hopeful that somehow, some way, the big changes in the outside world can be managed, if not trumped, by our local virtue, gumption, and smarts. Yet it is true that capital long since has been internationalized. The top profit-earning American corporations are oil companies, financial-service firms, and marketing entities that do all their manufacturing in China and won’t be manufacturing in Upstate New York any time soon.

A new study by two non-partisan economists suggests that there is a new normal called the “jobless recovery,” which rings true around here, where overall employment since the 2008 crash is still down: The number of non-farm jobs in September 2012 in the Buffalo-Niagara Falls area is 546,000, compared to 557,000 in September 2008.

Another study finds that there are few job opportunities for new entrants to the middle class, such that America tomorrow will consist of a few investors, some high-wage workers and entrepreneurs, tens of millions of low-wage workers, and an ever-shrinking middle class that consists principally of public-sector workers under political attack from every other cohort. If this is the new America, our corner of which has been a post-industrial playground for rent-seekers, what difference can Governor Andrew Cuomo’s $1 billion pledge to Buffalo make in our diverse $45 billion regional economy?

That was a sensible question well before Hurricane Sandy hit the New York City area, whose strong and growing economy—now disrupted and needing more than $30 billion just to get back to normal—supplies the subsidies that rain down on Upstate New York. The mega-trends of the US economy present UB president Satish Tripathi and Larkinville entrepreneur Howard Zemsky, Cuomo’s volunteer leaders of the Western New York Regional Economic Development Council, with a daunting enough task. After Hurricane Sandy, the damage wrought by climate change to the functioning New York metro economy seems a much more urgent issue than figuring out how to deal with the perennial challenge of what to do about faraway, needy, never-quite-right Buffalo. After all, the national Bureau of Economic Analysis says our gross metropolitan product grew, despite the 2008 crash, from $41.7 billion in 2007 to $45.1 billion in 2010. We may be losing population and jobs, but the numbers are still positive.

That’s in part because the Albany cornucopia still burgeons in an ongoing building boom that drove Harvard economist Ed Glaeser in 2007 to conclude that more billions in outside money won’t help the place, and that “the best scenario would be for Buffalo to become a much smaller but more vibrant community—shrinking to greatness, in effect.”

Governors and messaging

Trade, demographic, and technological megatrends keep adding challenges, yet yesterday’s commitments are still on the books. Albany is investing tens to hundreds of millions of dollars in new buildings for a new medical campus, after having spent tens to hundreds of millions of dollars in new buildings for the old medical campus, even while the mega-trend cluster of information technology, genomics, and telemedicine could make monkeys of the people who sign off on all those long-term bonds for buildings that fewer and fewer patients will ever have to visit.

But Andrew Cuomo is like his predecessor governors, Mario Cuomo, George Pataki, and Eliot Spitzer: He has enlisted smart helpers to make something change here, because Buffalo’s reputation is still—in significant part because of the negativity of the Buffalo Niagara Partnership’s campaigning—so, well, negative.

This community supports two professional sports teams, gets international kudos for its architecture and for its arts, and somehow ekes out actual GDP growth—and yet governors pledge transformation. George Pataki was in the transformation business when he set up “centers of excellence” in Albany, Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo, each tailored to the hoped-for specific strength of each area, each intended to provide the next regional economic driver. Albany got the center for nanotechnology, which by all reports seems to have succeeded, if at great expense. Syracuse got its center for new manufacturing; the self-aware, reality-checking regional business organization there seems still to be effective in agglomerating export-oriented strength from small manufacturers, though employment in the Syracuse metro is still down 10,000 since 2008. Rochester doubled down on its imaging technology, just as Kodak entered its death throes, getting a Center of Excellence in Photonics, but tech-oriented employment has been strong nonetheless, and the Rochester metro, which had 519,300 jobs in September 2008, had 517,700 jobs in September 2012. Buffalo got Pataki’s Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics. See above for regional job numbers.

And now Cuomo has his Regional Economic Development Councils. The good news about the one in Western New York is that there is some hard reality-checking going on. Co-chairs Tripathi and Zemsky have asked for advice from people with sterling credentials, including the Brookings Institution’s Bruce Katz and Amy Liu, as well as the international business consulting firm McKinsey and Company. Hundreds of volunteers have spent thousands of hours conferring. There isn’t a final report yet from the consultants, but the word so far is that the targets for the mixed bag of state subsidies, tax incentives, and infrastructure inputs will be these: advanced manufacturing, life sciences, and tourism.

There will allegedly also be a new item: something like the Pittsburgh model of an annual business-plan competition that will include, as they do in Pittsburgh and elsewhere, some ongoing technical and financial support. The biggest, fondest hope is to commercialize some of the intellectual property created at the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus.

The current paradigm

Here’s what Tripathi and Zemsky and Brookings and McKinsey and all those volunteers are up against: the Buffalo-Niagara Falls political economy that has, for a generation, steered billions of public dollars into projects that don’t arrest population decline, don’t raise household income, don’t clean up the water, don’t change or even mention income polarization, don’t address suburban sprawl, and yet keep a small group of business-class insiders very flush indeed. The community is awaiting the economic development solution that will come with great community buy-in, sterling Ivy credentials, and precisely engineered deliverables.

Cuomo is well briefed on what’s in place in Western New York. The evidence of his own unscripted statements is that he knows what other historically aware leaders have known, which is that economic and political change are connected.

It’s not a matter of money: Annually, the Buffalo area still gets at least $1 billion more in New York State tax dollars than it ships to Albany. In addition to salaries for SUNY employees, state troopers, the court system’s staff, and various other public employees, there is all that revenue-sharing—matching money to Erie County for much of what it does in social services, and extra funds to Buffalo for what it can’t do for itself given its radically overburdened tax base.

And then there are project funds, hundreds of millions already. There is highway-maintenance money. There are the SUNY 2020 funds going into rebuilding the medical school downtown—the one that was just rebuilt about 10 years ago on the South Campus of UB. The Buffalo Public Schools just finished spending more than $1 billion in state money on refurbishing buildings inside Buffalo.

We do not need to count the $153 million of New York State Power Authority relicensing money that was just sunk into the system of replica canals downtown. Many West Siders hope and pray that they won’t have to count the tens of millions that state officials would use for a diesel-exhaust concentration facility at the Peace Bridge. There are brand-new dorms and buildings and technology at Buffalo State College, which cost $300 million in state funds, and brand-new structures at UB, too. If the ill-considered $30 million building approved for the north campus of Erie Community College goes forward there rather than downtown, where the college should be consolidated, at least half the funds will come from New York state—the generous, reliable, locally reviled state that just now has Hurricane Sandy to clean up after.

Armchair economic development strategists will pick apart whatever program gets delivered after New York State spent $2.8 million on McKinsey’s consultancy. That’s inevitable and appropriate. But one wonders if some of the enduring challenges here, and some new ones, will make it into the final document.

What we won’t get, what we should get

We know that the political part won’t make it in. The lack of regional land-use planning to restrict the ongoing construction of housing and commercial space far outside the central urbanized region creates expensive externalities—like high utility costs and infrastructure over-build—that somebody beside the Regional Economic Development Council will have to address. Neither should we expect to see anybody who talks about job-creation strategies and business-plan competitions address the guaranteed ongoing failure of the Buffalo Public School system, more than 77 percent of whose students are from low-income households. (Since the 1966 Coleman study, replicated in 2010 in Buffalo by Ryan Keem, analysts have known that there is a .77 correlation between achievement and household income.) Regional school integration by household income is a crushing economic issue, but do not expect this to make the final report.

Nor can we expect climate-change issues, like the new preciousness of Great Lakes water, and especially the new preciousness of Western New York’s bountiful rainfall and exemption from the 2012 drought that hit 40 states, to drive the economic-development recommendation that now, right now, is the time to turn our infrastructure budget away from roads and toward cleaning up the water.

One worries that the report will trot out the old, discredited numbers about the millions and millions of alleged visitors to Niagara Falls, New York, who actually work out to be about two million people, mainly from here and around Upstate and Ohio, the rest of the numbers being an artifact of the repeat trade that the Seneca Gaming Corporation casino in the Falls gets—85 percent of whom are from here.

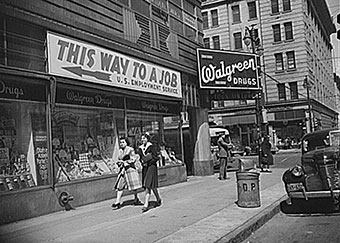

It will be enough that this report will endorse a programmatic alternative to the post-industrial, real-estate-centered norm here, so that maybe Buffalo will have a chance to be again what it was before it became a headquarters town, then a branch-office town, and then a dependency of Gotham—namely, an entrepreneurs’ town. During Buffalo’s age of heavy industry, as former University at Buffalo scholar David Perry pointed out in his landmark 1987 paper, ours was a headquarters town because of the peculiar geography of grain, steel, and victory in the Civil War. Then, even before World War II, the owners sold off their enterprises, and leadership here shifted mainly to bankers, lawyers, financial-service people, and people connected with real-estate development—not wealth-creators in the sense that the industrialists are, but wealth-managers and rent-seekers.

In the 1950s, whole industries started leaving, beginning with the defense complex and culminating with the end of the steel era in the early 1980s. Peak manufacturing employment here came in 1954, according to an old M & T Bank study, when there were 225,000 jobs in that sector out of a workforce of about half a million. Now, less than a quarter of the 546,000 workforce here is in “goods-producing” activities, and that includes things like food-processing for local needs, and not the hoped-for export-oriented manufacturing that brings other people’s money here.

When the economic development plan comes, the community should hope that it will get something it hasn’t had before: not a recipe for yet another tactical handout for yet another blockbuster public expenditure that will be built by today’s insiders, financed by today’s insiders, and targeted to today’s shrinking population, but rather a strategy, a long-term, nose-to-the-grindstone strategy, for incremental paradigm change for a smaller, closer, greener tomorrow.

Cuomo’s presidential ambitions will be best-served by the latter. If only the political revolution—for income-integrated schools, clean water, and sprawl’s end—were part of the package, too.

Bruce Fisher is director of the the Center for Economic and Policy Studies at Buffalo State College. His new book is Borderland: Essays from the US-Canada Divide, available at bookstores or at www.sunypress.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n46 (Week of Thursday, November 15) > WNY Economy 2.0? This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue