Next story: Christmas Time in the City

Comic art by John Jennings and Stacey Robinson at Hallwalls

by Jack Foran

Black Kirby

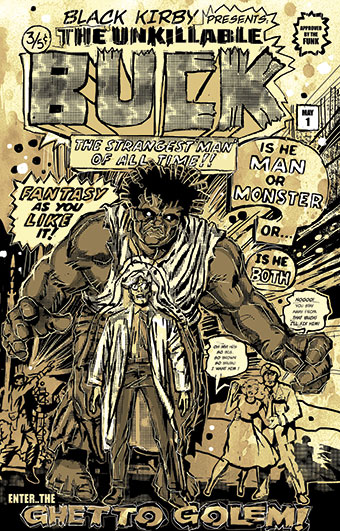

Black Kirby is the artist team of John Jennings and Stacey Robinson. The collective name is a play on the name of comic book artist Jack Kirby, inventor or co-inventor of any number of superheroes, such as Captain America, the Avengers, the Fantastic Four, Black Panther, and X-Men, and a comic book artistic style that became standard for the presentation of superheroes and the fantasy worlds they rescue issue after issue from ungodly forces of devastation and destruction. Black Kirby’s art imitates and parodies Jack Kirby’s in style and substance, adding an African-American—and notably contemporary—dimension.

The work is currently on exhibit at Hallwalls. In a talk at the opening about Jack Kirby’s art and their art, Jennings and Robinson spoke of their enormous regard for Kirby and his work, but, Robinson said, “We didn’t see ourselves there.”

That is, didn’t see African-Americans among—or prominently among—the pantheon of superheroes Kirby and his collaborators presented. Black Panther was the first black superhero. But a token black in the pantheon, and rather latecomer to boot. The comics noticed black people around the same time most of the rest of the white Americans took notice, as a result of the civil rights movement, and when elements of the movement were rejecting the idea of non-violence and opting for an alternative called “black power.” The most notable political manifestation of black power was the Black Panther party. The picture of Huey Newton in a wicker chair throne and black leather jacket and beret, with a rifle in one hand, a spear in the other. Power as menace. The Black Panther comic book superhero wasn’t overtly connected to the political Black Panthers or political black power, but played on the political movements. In terms of formidable. Scary.

But the full meaning of what Robinson said was not so much didn’t see themselves there as blacks, as didn’t see themselves there as contemporary blacks. As blacks with a sense of irony. You could even say a sense of humor. But a sense of getting beyond the 1960s and 1970s, getting beyond the movements. Not as abandoning liberation. But getting beyond what could be called the naiveté, the futility aspect, the ultimate fecklessness of the black power idea.

Black power is like the superheroes, the superheroes are like black power. The Black Panther superhero—like all the superheroes—was fantastical, fantasy. The Black Panther political movement was equally fantasy. The “worlds” in both cases were fantasy worlds. Plus, the connection implied the idea of blacks as others. Black Kirby plays on that idea, but not seriously.

The Black Kirby works include a remake of the Huey Newton picture in the wicker throne chair as a movie poster proclaiming: “The prequel to Alex Haley’s ‘Roots’. The Revolution will actually be televised. Right after Mork & Mindy but right before that reality show that white people like but black people don’t watch.”

Other items include remakes in superhero pictorial style of the famous shot of sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, each with one gloved fist raised, and another of Malcolm X as a superhero medieval knight. There is also a series of comic book cover takeoffs. One with a likeness of early era liberationist Frederick Douglass as the Old Testament prophet Moses. Another, for a comic entitled Crazy Watermelon Tales, with a cartoon black figure reminiscent of the howling monster on the cover of the initial Fantastic Four issue. The superhero pictorial style features superhero figures smashing through the picture plane amid a chaos of what is called in the comic books trade “Kirby Krackle,” a spatter of dots and energy streamer lightning (more than a little akin to Jackson Pollock’s paint spatter cum gestural energy lines of force, from roughly the same time period). The Black Kirby works are computer manipulations of original drawings, and range in style (often within the same work) from representational to digital gone wild collage abstractions.

An anomalous work consists of a grid array of seventy “pick” combs, each with a slogan definition or description of Black Kirby. “Black Kirby is a posse.” “Black Kirby got next.” “Black Kirby fights the power.” “Black Kirby is in the details.” “Black Kirby has razor blades in his Afro.” “Black Kirby is high in fiber.” “Black Kirby listens.” Etc.

This art is about many things. About appropriation, about pop, about hip-hop, about where blacks are today in the long struggle. The exhibit continues through December 21.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n49 (Week of Thursday, December 6) > Art Scene > Comic art by John Jennings and Stacey Robinson at Hallwalls This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue