Maid of the Mist, SEQRA, and the Schoellkopf Power Station

by Geoff Kelly

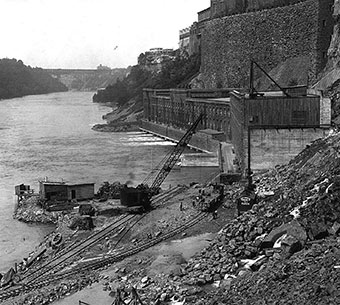

On Tuesday, Empire State Development Corporation called a press conference at the Niagara Gorge Discovery Center, which sits above the ruins of the historic Schoellkopf Power Generation Station #3, to dispute claims made in a pending lawsuit that the plan to build a boat storage facility there poses a threat to the environment and to the integrity of a historic site.

The state, through ESDC and the Niagara Power Authority, which owns the land, provided the site to the Glynn family, the operators of the Maid of the Mist boat tour franchise on the American side of Niagara Falls. The Glynns lost the franchise on the Canadian side after the contract, a 25-year deal renewed in 2008, was re-opened to competitive bidding last year—the result of a public outcry over what seemed to be a sweetheart of a no-bid deal. In losing the Canadian side of the business, the Glynns also lost the boat storage facility they’d used for decades, which sits on the Canadian side of the Niagara River.

The Glynns lost the Canadian franchise to Hornblower Cruises & Entertainment, a California company, which is suing New York State to open the bidding process for the American franchise as well. Hornblower insists that they’d pay more for the right to run tours on the American side than the Glynns do, just as they are paying the Province of Ontario more than the Glynns did for the Canadian side of the business. The Glynns, who have operated the Maid of the Mist since 1971, signed a new 40-year deal with New York State in 2002. That contract was re-opened and the terms changed last year to include the use of the Schoellkopf Generator site after the open bidding process for the Canadian site left the Glynns without a place to park their boats in the winter.

The group suing to prevent the construction of a storage facility on the Schoellkopf site is called the Niagara Preservation Coalition. These and other changes to the original agreement, the Coalition argues, substantially changes the states agreement with the Glynns and therefore nullifies it.

The Niagara Preservation Coalition’s president is Lou Ricciuti, who has been a frequent contributor to this newspaper for a dozen years, writing about the historic and environmental legacy of Niagara County industry, with special emphasis on the role Niagara’s plants and mills played in the early days of the Manhattan Project and the post-World War II atomic era.

Ricciuti argues against the use of the Schoellkopf site for a boat storage facility, which would entail building a 25-foot-thick concrete pad on top of the remnants of the plant, on two counts.

First, he says, the site’s historic significance is international in scope. This was where the Tesla/Westinghouse and Edison/J. P. Morgan “Battle of the Currents” unfolded—the fight between advocates of alternating current and direct current as the means of powering American homes and industry. It is where mechanical energy was first harnessed at the cliff known as the High Banks, where direct current electricity was created and used on the largest scale to that date, followed by the competing development and eventual implementation of transmittable AC electrical power over long distances, thus powering things like your computer screen and the light over your desk.

Second, the site is likely environmentally compromised, contaminated by the industrial activities that took place there exactly because of the electrical power available at this one site. Metallurgical and chemical industries sprouted there and grew to internationally known companies such as ALCOA Aluminum and the Oneida Silver Community, among others.

On those two counts, Ricciuti says, the project required a thorough environmental review, under the State Environmental Quality Review Act, or SEQRA. Instead, the state has tried to fast-track the project and the environmental review in order to begin construction of the facility this spring, so that the Glynns can store their boats there this winter. This fast-tracking, Ricciuti says, stands in contrast with the state Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation’s previously stated position that such a project would require an extensive environmental review.

Thus, Ricciuti says, the formation of the Niagara Preservation Coalition and the lawsuit, which Ricciuti says must have been expected by those pushing for this private operation detrimental to an internationally important scientific and cultural legacy. Last week the group won a temporary injunction, stopping the site preparation work that had already started, with long-armed backhoes stripping away the top portion of the Schoellkopf plant. That injunction will be reviewed this Thursday by state Supreme Court Judge Catherine Nugent-Panepinto.

In the meantime, the temporary injunction and the lawsuit have precipitated a full-court press designed to question Ricciuti’s credibility and motives. He’s been characterized as a crank, a job-killer, and a tool of the Hornblower company, which encouraged him to form the Coalition and find a lawyer. (Linda Shaw, the Coalition’s lawyer, knows Ricciuti from a lawsuit associated with the former Lake Ontario Ordinance Works, which Ricciuti has written about for this newspaper.) We here at Artvoice have known Lou a long time, and whatever else we may call him from time to time, he’s not a shill for anyone. And Tuesday’s press conference suggests that the state agencies understand that the claims in the lawsuit are credible: Pete Gallivan, the former TV news reporter who is now a spokesman for ESDC, acknowledged that the site is historic but characterized the boat storage project as a means of stabilizing and restoring, not displacing, the historic site. In other words, the state is trying to out-preservation the preservationists. But, as Ricciuti pointed out to a Niagara Gazette reporter, you don’t preserve something by pouring 25 feet of concrete on top of it.

In the end, this lawsuit is about three things. First, it’s about the history of the site, which is well documented. This isn’t an “opinion on the rocks,” says Ricciuti. It’s a federal designation that was just passed and posted to the federal register by the National Parks Service and Congress, as of March 22 (www.nps.gov/history/nr/feature/places/13000029.htm).

Second, it’s about the integrity of SEQRA, the most significant legal tool those concerned with the quality of the state’s air, water, and soil have at their disposal. In recent years, the power of SEQRA has been diminished by court decisions forgiving developers and government agencies the obligation of performing the proper environmental reviews the law requires, and by the practice of fast-tracking those reviews when they are required, or issuing “negative declarations” of environmental impact without sufficient study. Ricciuti’s group is asking that this project be subject to both the letter and the spirit of SEQRA laws.

Third, it’s about environmental contamination. There is good reason to believe the site in question is compromised, given past activity there. Ricciuti took soil samples from the site and sent them to a lab for analysis, which is more than the state has done. Some of Coalition’s samples exceeded both residential and commercial hazardous materials criteria, and a spill report was officially made to the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Spill Response Hot-line.

Ricciuti is also increasingly worried that projects like these amount to quiet cleanups, erasing the history of a site’s uses and the questions and concerns that history provokes, or should provoke. In this particular case, the motivation seems simply to be giving the Glynns what they need to hold on to what’s left of their no-bid concession. But in recent years, Ricciuti points out, some of the area’s most historically significant sources of dangerous and abiding contamination have gone under the wrecking ball with scarcely a word about what happened at them. Among those disappeared sites are the chemical and metallurgical plants that used to line Buffalo Avenue, some of which handled very dangerous chemical and radiological materials for both commercial and war efforts from the mid 19th century right up until today.

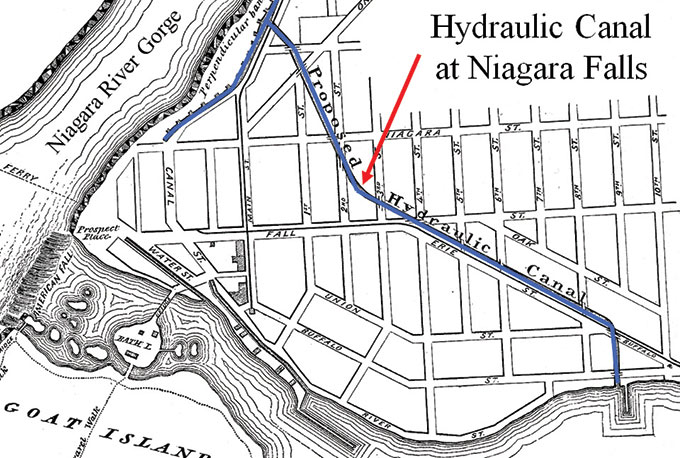

Many of these plants discharged waste into the Upper River, upstream of the intake for the canal that cut across the city and fell through tunnels in the gorge to turn the Schoellkopf plant’s turbines. Construction of that canal began in 1853. The Schoellkopf plant collapsed into the gorge in 1956. In the interim, all manner of waste flowed through it and into the tunnels that factories bored in the cliffs to convert the water’s motion into mechanical and electrical energy. Eventually, after the plant’s collapse, the canal was filled. Need one evoke the memory of another famous canal in Niagara Falls to raise concerns about what it was filled with? Indeed, after the Love Canal controversy, the buried canal that carried water to the Schoellkopf power plant was designated an uninvestigated Superfund site. That would suggest that the site of Schoellkopf plant, which sits on an international waterway, demands more than a cursory environmental investigation before it is further developed for any purpose.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n15 (Week of Thursday, April 11) > Week in Review > Maid of the Mist, SEQRA, and the Schoellkopf Power Station This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue