Next story: When Homeowners Can't Clear Sidewalks, The City Should

One of the More Curious Specimens

by Mason Winfield

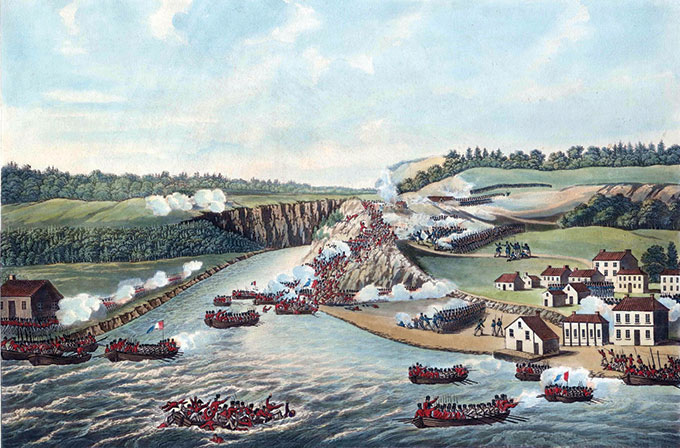

December 1812: General Alexander Smyth

Among historians, the American commanders in the first half of the 1812 clash are a running joke. I can think of four from the Niagara alone who, in any other war, might have been shot: Captain Nathaniel Leonard (1768-1844), whose boozing distraction opened Fort Niagara to a massacre; General George McClure (1771?-1851), who let his Canadian allies burn Niagara-on-the-Lake and left Buffalo to take the payback; Brigadier General John Parker Boyd (1764-1830), Fort George’s commander during its American tenancy, later found to have been the longtime agent of a foreign government (Spain, FYI); and, ah, yes…the blustering General Alexander Smyth (1767-1830)—“One of the more curious specimens of American generalship,” according to Canadian author-telejournalist Pierre Berton.

If Alexander Smyth isn’t the Army’s all-time wing-nut, I’d love to know a better candidate. One part of me chortles that Irish-born Smyth was as much a Buffalonian as Mark Twain. In Virginia as a boy, by 1812 Smyth practiced law and served in the state House of Delegates. His only military experience was translating French troop manuals, hence he should not have been outraged that someone else was named first Commander of the Army of the Niagara. He was no team player, either. Sulking in camp with most of the regular soldiers, Smyth cost the US the Battle of Queenston Heights. Had he pressured Fort George as ordered—if he’d just touched down and then run off—it would have nipped the winning British rally. He was a strange choice for the next top dog.

Smyth’s first plan as the Niagara’s second commander was an attack on Fort Erie, which his troops “will conquer or they will die!” Day broke November 28 on one relaxed invasion. Not till late afternoon was everything ready, and by then the boats in the Navy Yard at Scajaquada Creek were heavy with snow, and the British side of the Niagara teemed bayonets. Both sides had to be bloody sick of “Yankee Doodle,” which the manic pipers had been playing for hours straight. But Smyth was nowhere in sight. He’d called an out-of-cannon-range council to decide whether Canada really deserved invading. Maybe buffaloed by a British opponent, popular Lt.-Col Cecil Bisshopp, and maybe afraid of getting hung out to dry like he’d done his predecessor, Smyth gave the order to “Disembark and dine!” In days, most of the troops were encamped on Flint Hill, the windy high point on Judge Granger’s farm at the east end of today’s Forest Lawn Cemetery.

Little other noise was heard along the frontier except “the sonorous cadences of General Smyth’s proclamations,” which he even published as if they were the speeches of Cicero. “Hearts of War!” begins one gusty standard. Another closed with the line, “Come on, my heroes!” The impression that regiments would stand in the sleet to listen to these bloviating melodramas is a gesture of high comedy. Smyth’s troops whacked the trees with swords and rifles while enduring them.

Fancying himself an orator opened Smyth to ridicule. Sending his army to a miserable, undersupplied winter quarters without waging a single campaign subjected him to fury.

Soldiers deserted in handfuls. Others out on patrol lobbed shots in the direction of Smyth’s tent, which had to be moved constantly and was said to have taken seventeen hits. Some officers speculated that Smyth might be a traitor. Militia General Peter Porter ventured that he was just a coward, but he did so in the pages of the Buffalo Gazette, leading to a daybreak fake-duel on December 12. On December 22 Smyth took leave to join his family in Virginia. He was disbanded—dropped like a smoking crap grenade—from the Army. While eventual Commanding General of the US Army Winfield Scott recalled Smyth as “well-read, brave and honourable,” history concurs with his follow-up reflection, that Smyth had “no talent for command and made himself ridiculous on the Niagara.” (John R. Elting was more direct: “That peer of military stupidity.”)

Smyth’s “excellent social qualities” stood out once war was in the rear-view. A well-connected Congressman, he left his name on a Virginia county whose historians guard his portrait as zealously as if they think you want it for a dartboard. A long-range look at his likeness will cost you $100. (I’ve seen an 1805 profile of Smyth. He’s a long-skulled Anglo. Looks a bit like Hugh Laurie (House) minus the scraggle. But Smyth has been memorialized in verse.

On Washington’s birthday in 1814, Smyth petitioned Congress to be reinstated in the resurgent US Army, dramatically requesting to “die for his country.” Uproarious toasts for that wish to be granted were raised that night all over the capitol. Found in the morning on a door-panel at the House of Representatives was a punning verse in the style of the age composed by some hung-over wit:

All hail, great chief! who quailed before

A Bisshopp on Niagara’s shore:

But looks on Death with dauntless eye,

And begs for leave to bleed and die.

Oh my!

Mason Winfield is the author of 10 books, including Ghosts of 1812 (Western New York Wares, 2009), the only recent popular history of the 1812 war on the Niagara.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n2 (Week of Thursday, January 10) > One of the More Curious Specimens This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue