Next story: The Director's Cut

Remembering Spain Rodriguez

by Ishmael Reed

...and the extraordinary cultural landscape of Buffalo in the 1950s and 1960s

When the great poet Lucille Clifton died, the New York Times said that she was a member of a group of Buffalo black intellectuals. They left out the Irish, Italian, and Jewish American intellectuals, artists, writers, and musicians, who from 1957 (I was 19) to the fall of 1962, when Dave Sharpe and I left for New York on a Greyhound bus, banded together to create a Renaissance in the city. Among them were Wes Olmsted, Ed Callahan, Bill Baker, Gino, Carl Tillman, Teddy Jackson, Priscilla Thompson, Winnie Stowers, son of the great Duke Ellington vocalist, Ivie Anderson, folk singers Lisa Kindred and Ray Smith, who was called the Harry Belafonte of Buffalo, and Walter Cotton, who would go to New York, where he acted in such films as Cotton Comes to Harlem. Another member of our group was the musical prodigy, the late Claude Walker, who was playing hard bop as a teenager. Lucille was part of this circle.

Our gathering places were Laughlin’s, Café Encore in Allentown, Mary Seibert’s at Northland and Jefferson Avenue. We listened to Jimmy Smith at the Pine Grill and Italian jazz musicians at the Anchor Bar, or we jammed at the Colored Musicians Club, where legend has it that Milt Jackson discovered Buffalo’s Wade Legge. We acted in plays at the Michigan Avenue YMCA, where Lucille and Fred Clifton performed in The Glass Menagerie, which was called “poetic and sensitive” by the Buffalo Evening News, and where I played Creon in Antigone. At the Jewish Center’s Theater in the Round, I performed in The Death of Bessie Smith as a member of a cast led by Manny Fried and Betty Lutes, and before I left town Fred Keller wanted me to try out for the role of Sancho Panza.

We attended poetry classes at the University of Buffalo led by Myles Slatin and wrote radical articles for the Empire Star, founded by the great hero of the Tulsa race riots of 1921, A. J. Smitherman, who, within the last 20 years, has received the place in history that he deserved. (We took up a collection for his granddaughter’s soon-to-be husband, the late Ortiz Walton, so that he could go to Boston to try out for a job as bassist for the Boston Symphony. He passed the audition.)

Buffalo was jumping in the 1950s. There were two jazz clubs on William Street, which was our 12th Street and Vine. At the Zanzibar, I heard James Moody, Carman McCrae, and Miles Davis. It was September 21, 1955, when we saw Miles get out of a cab and enter the Zanzibar. We were standing on an opposite corner. We were in awe. Such was the music scene in Buffalo that you could catch Wade Legge playing in a dive located on Ferry near Jefferson Avenue.

Kai Winding and Della Reese were available at Mandy’s. Lisa Kindred was a waitress at the Jazz Center, where I met Cannonball Adderley. She went to New York, performed with Bobby Dylan, and became a recording star with her rendering of the blues.

There was a Buffalo disc jockey named Joe Rico, to whom Illinois Jacquet dedicated a tune called “Port of Rico.” For rhythm and blues there was a disc jockey named Hound Dog, and I had my own jazz show on WBFO FM, the University of Buffalo radio station.

When local Buffalo historians critics write about this period, they usually leave out either the black part of this Renaissance or, as the Times did, the white part. The local historians contend that things started happening when Ted Berrigan or somebody came to town.

The fact that Spain Rodriguez was creating art in Buffalo at the same time certainly makes this period worthy of a book by somebody who would pull the pieces together. From the mid-1950s to the beginning of the next decade, Buffalo was the scene of one of the most extraordinary creative moments since Mark Twain used to stroll down Delaware Avenue (then Delaware Street) or when black poet James M. Whitfield (1823-1878) cut hair in a Buffalo barbershop.

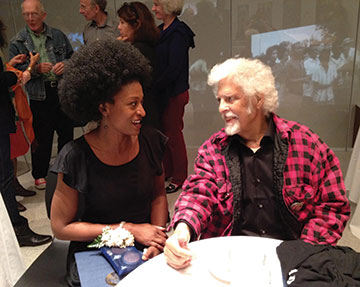

Spain’s widow Susan said that Spain remembered meeting me in Buffalo. I don’t remember. He was a member of a motorcycle gang. I was a nerd. This wouldn’t be the first time that Spain and I would miss each other. In 1965, Walter Bowart and I founded the East Village Other. When Spain began drawing cartoons for the newspaper in 1967, I was leaving New York for the West Coast. We finally met in San Francisco when I asked Spain to contribute to my magazine, the Yardbird Reader. One of his cartoons, Manning, about an out-of-control detective who brutalizes minorities, was printed in an issue.

On March 16, 2013, hundreds of cartoon aficionados and 1960s counterculture types (on crutches, with hip replacements) showed up at San Francisco’s Brava Theater for a memorial to Spain Rodriguez. It was a moving and tender event as speaker after speaker recalled incidents in the career of a cartoonist whose values were out of step with an age that prefers the racist cartoons of Robert Crumb or abstract art, so nonthreatening that bankers can decorate their walls with it. Spain hated abstract art, with its flat surfaces and its nonengagement. He prefered three-dimensional drawings. He said that he learned more about art by drawing machines, when he worked in a factory.

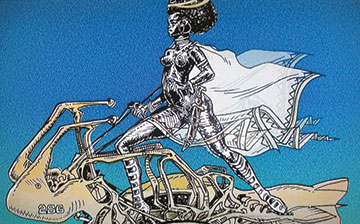

Bankers get the worst of it in Spain’s cartoons. The rich are cannibals who get mowed down by Spain’s Trashman. Outside of their dinner party, homeless veterans push carts. He was a social realist like Diego Rivera. His cartoons carried his politics on their sleeves. But like Rivera, he wasn’t a crude polemicist; the guy could draw.

Applause greeted the screen behind the stage that showed Spain’s cartoon heroes, including women who could kick butt as well as any man. Such was the demand for seats that my daughter and I showed up at one o’clock for the memorial that began at two. The lobby was decorated with blown-up panels of Spain’s drawings, and free tacos were on hand. Tacos that had pictures of Spain’s superheroes on their faces.

Before the ceremony began, the audience was shown photos of Spain as a child and as a family man. The memorial opened with a rendering of movement songs like “We Shall Not Be Moved,” performed by the No Illusions Band. Many in the audience teared up when Susan Stern, his spouse, at the conclusion of three black guys—Preston J. Turner, Fred Ross, Clif Payne—belting out “Stand By Me,” a song made famous by Ben E. King and written by King, Jerry Leiber, and Mike Stoller, said that it was Spain and hers bonding song. The music was followed by Susan Stern’s film, Trashman: The Art of Spain Rodriguez. In it, he was described by Susan Bright as “a trickster, card, and a bugger.”

Crumb called him “part crazy artist, part left-wing radical, and part working-class Latino hood.”

Spain was Minister of Propaganda for the motorcycle gang, the Road Vultures. Crumb said that he admired Spain’s background landscapes.

He was a cartoonist whose idea of dystopia was a Dan Quayle presidency. The first lady, Marilyn Quayle, spends her lunch hour fellating Mel Torme.

He was an advocate for a more just society; his hero was Che Guevara. The last time that I saw Spain was when gathered to pay tribute to Bob Callahan, Spain’s partner in creating the noir series The Dark Hotel. Before that we had lunch with Art Spiegelman and the late Bob Callahan at the Embarcadero. David Talbot, one of the founders of Salon.com, remembers when Callahan and Spain pitched the idea for The Dark Hotel.

“By the time I met Spain, he was pushing 60, happily married to documentary filmmaker Susan Stern and the father of a daughter named Nora,” Talbot said. “But he was still pushing the edges with his work. One day, near the turn of the millennium, he and a sidekick—cartoon story-writer Bob Callahan—appeared in the offices of Salon, which I was then editing, carrying sketches for a cartoon series they called The Dark Hotel. Managing editor Gary Kamiya—who became the story editor for the series—and I were immediately captivated by The Dark Hotel’s weird tunnel into the American psyche. Set in a seedy San Francisco Tenderloin hotel, the series—which ran for several months in Salon—featured Balkan war criminals on the lam, CIA drug experimenters, George W. Bush bagmen, and other creatures from the dark side of Spain and Bob’s America.”

My daughter, Tennessee (Spell Albuquerque) and I left after the showing of the documentary about an artist who never forget his Buffalo roots. He always included Buffalo scenes in his drawings. Places like the Kitty Kat, a dive where my friends and I had a run-in with the police.

I remember visiting Buffalo once and walking into Freddie’s Doughnuts. I asked the clerk whether he knew that a famous cartoonist named Spain Rodriguez did drawings that included Freddie’s Doughnuts. He didn’t have the slightest idea of what I was talking about. Somebody said that Spain never achieved the fame of Robert Crumb. Maybe it’s because Spain’s black women are beautiful and majestic. They ride on the back of birds instead of licking toilets. No neo-Nazi magazine is going to honor Spain by reprinting his work.

Ishmael Reed’s latest novel is Juice! He can be reached at ishmaelreed.org. Printed with permission of the author.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n21 (Week of Thursday, May 23) > Remembering Spain Rodriguez This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue