Subtle Resistance

Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell at the Anderson Gallery

Subtle Resistance at the Anderson Gallery is about how artists Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell survived and prospered in the male-dominated abstract expressionist art world of the 1950s and 1960s, partly due to the moral as well as financial support of gallerist Martha Jackson, partly by means of artistic strategies they employed to make art that was neither quite in the abstract expressionist mold nor completely alien to the prevailing aesthetic currents of that cold war era.

Abstract expressionism was alternatively defined by the two towering art critics of the era, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, as “formalism,” as Greenberg decreed, about the materials of artmaking, paint on a flat canvas, and “action painting,” as Rosenberg analyzed, about painting as the painterly event, gestures. About all the pair agreed on was that figuration, the depiction of recognizable imagery, was out. Verboten.

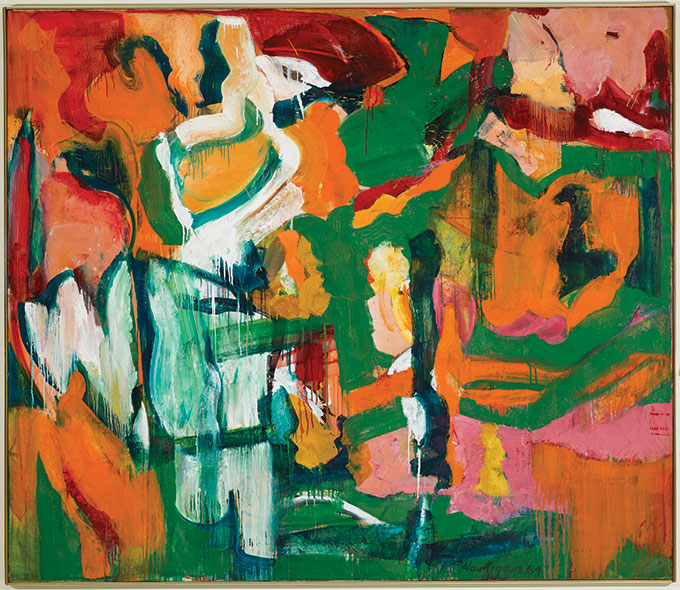

Hartigan and Mitchell and Jackson were much less authoritarian, dictatorial. “I want an art that is not ‘abstract’ and not ‘realistic,’” Hartigan wrote. She made works that present fractured images, ambiguous, but suggestive of reality outside the particular canvas, a meaning and for want of a better term message beyond the mere act of painting and abstract forms.

Her painting entitled Paper Doll-Bride is one of a number of works constituting an essentially feminist critique of traditional gender role assignments and attendant limitations and impositions.

Mitchell’s work is more genuinely abstract, but often with art history references. Art history implying a time and an art—the validity of a time and an art—before abstract expressionism, an idea some abstract expressionists might have found puzzling.

Her painting entitled Begonia is like some gorgeous impressionistic work, perhaps by Monet, perhaps by van Gogh. Her several paintings called Sunflower, then with different Roman numerals, allude as to subject matter to van Gogh, and in terms of series to Monet, but visually to Cy Twombley (so the art history references are not limited to before abstract expressionism).

Nor does Hartigan shy from art history reference. Her stunning When the Raven Was White, based on a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, has a distinct Matissean quality, in terms of its languid tropical vegetal imagery and fauve-reminiscent bright colors. It features a head of a white bird, and grasses and flowers that become arms and hands above, grief tentacles below. She wrote that “while the painting was in progress, my friend and dealer, Martha Jackson, died. The raven became a ghost of her pet parrot; the other images are associated with her love of nature, her hand reaching to help and be helped; the content of the work is a combination of her vulnerability and her ferocity…”

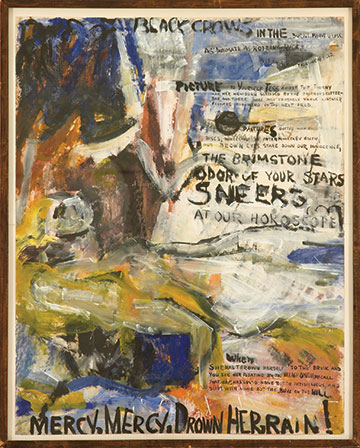

Both artists have works particularly related to the poet Frank O’Hara, with whom they were close friends—Hartigan would talk with him daily on the telephone—and who as a gay man caught in the swirl of the abstract expressionist art world—O’Hara’s day job was with the Museum of Modern Art—might have experienced some similar problems to Hartigan’s and Mitchell’s with the macho contemporary culture.

On display are two of a series of paintings Hartigan did on poems by O’Hara, in particular his poem called “Why I Am Not a Painter,” on the parallel subjects of a friend’s painting about sardines that ultimately leaves out the sardines, and his poem or series of poems about oranges that never gets around to mentioning oranges.

The Mitchell painting is a triptych blocky abstract work—painted in response to the poet’s tragic and senseless death—he was run over on a beach on Long Island by a dune buggy—on O’Hara’s poem in three stanzas called “Ode to Joy,” which begins “We shall have everything we want and there’ll be no more dying…”

Something else the two painters had in common as well as in common with Martha Jackson was that they all hated labels, categorization, pigeon-holing. A quote on the wall from Jackson, from a 1965 letter, reads: “I only believe in art—never in fashion—the word and attitude to me is ridiculous.”

Fifty years later, abstract expressionism, which was thought at that time to have wiped the slate clean and started the project over—or maybe ended it—turns out to have been a fashion.

The Hartigan-Mitchell-Jackson exhibit was curated by Angelica J. Maier as part of her MA. work at UB. It continues through August 4.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n22 (Week of Thursday, May 30) > Subtle Resistance This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue