Next story: Buffa-Love From the Business Alliance of Local Living Economies

Surviving Tigers, Imaging Cougars

by Bruce Fisher

Summer readings on nature and fantasy

Ever since summer camping became a part of the calendar, many children around here have the great experience of leaving home for a week or two, or even for the whole summer, to get to see nature up close. A favorite destination for some has been the century-old camps of Algonquin Park: At Pathfinder, Tanamakoon, Northway, and others, kids from about age eight through high school sleep on cots in platform tents or in rustic dormitories, eat meals and wash up in log mess halls, learn how to paddle and portage canoes, roll kayaks, start campfires, exist without electronics, write letters longhand, negotiate with older kids. Above all, they learn about nature. Sunset becomes a meaningful event, because the only light is the battery-powered thing that helps you to the outhouse. Loons cry, owls hoot, and wolves yip and howl. The forests are dark, and in August, when the cold of the north starts to show itself, it’s definitely time to come back to warmth, the normalness of school and of the built environment.

Any parent sending a tween or teen to camp this summer should send that wilderness-bound camper equipped with two books: one to challenge the kid’s understanding of the human impact on the North American forest, and one to scare the bejesus out of him or her.

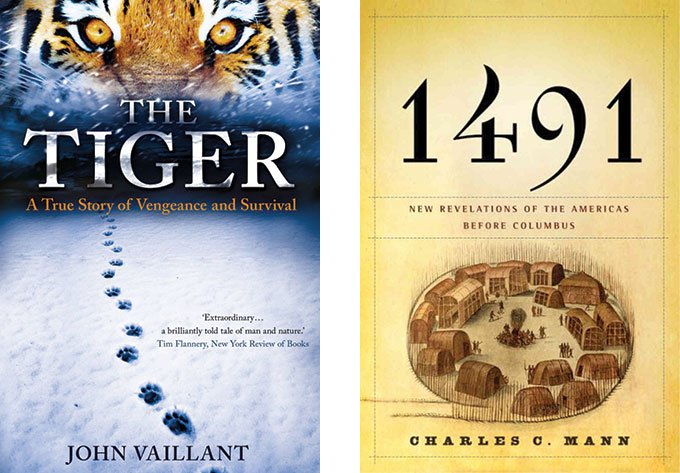

Scary first. Canadian journalist John Vaillant’s Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival is a very fine piece of work that will disrupt the romanticism of anybody who likes the idea of camping where big predators are a part of the natural order. Just an hour’s drive from Buffalo is Allegany Park, home to 200-pound black bears that sometimes range all the way to East Aurora to raid chicken coops and apiaries and berry-patches. Some young people I know well did once and still do get enthusiastic about wolf packs hunting moose not even three hours’ drive from the Toronto Science Center, right near where we typically rent the canoes, just the next pond over. Vaillant’s book is about a creature that lives in snowy northern forests on the easternmost part of Russia where the woods meet the Pacific Ocean, just north of China and North Korea in a region even more remote than Siberia, an apex predator that eats deer and wild pigs, but that also kills and eats wolves, and bears, and hunting dogs, and armed men.

We live in a part of North America that was once part of the range of the cougar, the big tan cat that has re-established its range out West, that attacks joggers in California and eats dogs in suburban Boulder, California. Nation du chat, cat people, is the term French translated as the self-designation of the Iroquoian-speaking people who lived here until their conquest and absorption by the Senecas in 1651; the reference was not to bobcats or to lynx but to cougars. The Ontario Puma Foundation publishes a map of reliable sightings and other evidence of a re-established population of cougars everywhere from the cross-border suburbs of Detroit through the émigré Scottish-farmer flatlands of the Ottawa, Thames, and Grand River valleys to the easternmost part of the Niagara Peninsula, i.e., the woods and fields just inland from where much of Buffalo goes to the beach. The Bruce Trail, which is a belt of green that connects Georgian Bay straight south to Hamilton and then east along the Niagara Escarpment to the Niagara River right near the Butterfly Conservancy, may be the corridor for migration for breeding populations of cougars now resident in the American and Canadian Midwest. Or maybe we just want to think that they’re here. The Ontario enthusiasts have their counterparts in the Eastern Puma Research Network. There’s also the Cougar Rewilding Foundation, which posts an upbeat masters thesis entitled “Recolonization of the Midwestern United States by Large Carnivores: Habitat Suitability and Human Dimensions,” by Julia Smith, who praises the adaptability of wolves, bears, and mountain lions.

Vaillant’s book about the arduous life-ways of the forest-dwelling people of the forests of Russian Manchuria, and of the tigers who sometimes eat them, is a strong presentation about what inevitably occurs in the native territory of an apex predator. Human-tiger interaction is not happy. It never has been. Vaillant’s focus is on the personalities and the political dimensions of finding the 500-pound beast that stalked and killed and ate a poor hunter named Markov, and then, wounded, starving in winter weather of 30 degrees below zero, stalked (for days!) and killed and ate a very young man just back from a horrible term of military service in Chechnya.

Go to the globe, the part that shows China, the two Koreas, Japan, and Russia: North of the Amur River that forms the border between Russia and China, inland from Vladivostok, are the forests mountains and valleys where about 500 Amur tigers remain, out of a pre-Perestroika population that may have been 20 times as high. Capitalism’s reintroduction to the Russian Far East is a big part of the story here; the heavy hand of the former Soviet state prevented poaching but only after a period of ideologically sanctioned slaughter of tigers, leopards, and other wildlife in that exotic Manchurian landscape, in which very, very poor Russians eke out a subsistence, alongside some few thousand members of indigenous groups for whom tigers are at least totemic and possibly also divine. After the Soviet Union collapsed, and gangster capitalism exploded, so too did tiger-slaughter. The big beasts are sought now by Chinese, who are now rich enough to purchase their heads, penises, dried blood, pelts, and sometimes whole carcasses; the meat’s taste is appreciated, too.

As raw and wild as the Amur tiger’s range still is, the opposite is true in the Americas described Charles Mann in his masterful, challenging summary of recent scholarship on the world of the pre-conquest Native Americans. The book is 1491: New Revelations of the Americans Before Columbus. Most of the surprises that Mann presents consist of the work of archaeologists, paleo-botanists, anthropologists and other scholars of South and Central America, the most counter-intuitive of which concern the shape of the Amazon rain forest. American students of Native Americans tend to focus most on the Northeast, the Plains, and to some extent the American Southwest; working northward from the great empires that were in place when Euro-thugs Pizarro and Cortes arrived, Mann does a great job of connecting lots of disparate information about crops, agriculture, social organization, architecture, and other matters. That’s how he connects the very disturbing stories about the march of horror that swept in and depopulated northern North America so effectively, so swiftly, so very-nearly completely, even before the first waves of European settlers arrived in any numbers.

The politics of writing about Native America have always been front and center in every analysis. First came the triumphalists of the 19th century, typified by Francis Parkman’s books about the French and British conflict. Then came the boots-’n’-saddles histories of the American West, celebrating the victories over the horse-tribes. Then, in the 1960s, the revisionists arrived, with popular histories and celebrations of Native American spirituality, and Francis Jennings’s critique of the triumphalist tone. Who, the revisionists asked, who was the real savage here? To Jennings and his generation, the Europeans were unquestionably the evil-doers—killers, exploiters, despoilers. But then came Henry Dobyns, whose research into the demography of pre-conquest Mexico did two surprising things to the highly angry dispute between conventional historians and revisionists. First, Dobyns read the Spanish-language sources, something that the English-centered scholars, um, forgot. Most important, Dobyns counted.

The native population of the Americas did not decline by one-tenth, as the term “decimated” signifies. The native population of the Americas declined almost entirely to zero, and did so because of disease. The emptied, “widowed” landscape into which wondering Europeans wandered was no wilderness, either. North America wasn’t an Eden: it was very much a cultivated garden, as Mann skillfully collates the results from all the various disciplines of investigators, including wildlife-population specialists, who have a great deal to add to general knowledge about those great masses of protein that Americans nearly and then completely wiped out, the bison, and the passenger pigeon.

’Tis the season of embracing true nature. These books are nature to advantage dressed.

Bruce Fisher is director of the the Center for Economic and Policy Studies at Buffalo State College. His recent book, Borderland: Essays from the US-Canada Divide, is available at bookstores or at www.sunypress.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n29 (Week of Thursday, July 18) > Surviving Tigers, Imaging Cougars This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue