Next story: Tolbert Campaign Begins

Bennett's Best

by Charlotte Hsu

What’s it like to be valedictorian of a persistently low-achieving school?

Cheyenne Ketter-Franklin is valedictorian of Bennett High, one of Buffalo’s worst-performing schools. It’s the type of institution whose problems people sum up using terms like “urban” and “inner city.” In 2010, the state slapped the school with the label PLA: “Persistently Lowest-Achieving.” Privately, many local residents will skip the euphemisms and admit to thinking of Bennett as some kind of hellhole.

Here are some things you may already know or suspect about the school: 101 students dropped out in 2011-12. The four-year graduation rate for freshmen entering in 2008 was 31.6 percent. One of Cheyenne’s best friends, Breone Boles, says it’s not unusual to hear a classmate tell a teacher, “Fuck you.”

Here’s what may surprise you about Bennett: Cheyenne says there’s no other high school—public or private—that she would have rather attended. If she could roll back time and start her education over again, she would still choose Bennett.

•

Some may think that Cheyenne’s loyalty is misplaced or naive. She knows what people in the community say about Bennett:

Bennett sucks.

I would never send my kid to a place like that.

“They feel it’s a backup school—kind of like, this is something that you dismiss,” Cheyenne said.

Maybe you’ve said things like this yourself. Lots of people do. William Franklin Jr., Cheyenne’s father, said an acquaintance once told him that an “A” at a school like Bennett was like a “B” in the suburbs. Breone said she has gone to recruitment fairs where parents refuse to take her brochures. People imagine a place where students smoke in the bathrooms and fight in dilapidated hallways every day.

But that’s not what it’s like, Cheyenne said: “I find it inappropriate and discouraging when people think that way and have those predesignated thoughts when they don’t know.”

It’s not that Bennett is trouble-free. The institution’s problems are varied and obvious: Fights do break out. Girls do get pregnant. Not all students feel safe. Some classrooms are loud and poorly managed. Tracie Batcho, a favorite teacher of Cheyenne’s, said when she first started at the school, her biggest shock was the language teenagers used to address adults: “F you, F yourself.”

But Bennett is also a place where young people find direction, where teachers like Batcho helped Cheyenne discover what she wanted to study in college. At Bennett, Cheyenne met Breone, learned about herself and the world, tutored classmates to keep them from failing, and watched some students overcome staggering odds to graduate—like the young mothers who came to class day after day, determined to earn a degree because they messed up once and didn’t want to make another mistake.

So when Cheyenne hears people pass judgment on Bennett, it frustrates her because she knows the truth is more complicated.

In reality, the dirty, rotting hallways that people imagine don’t exist. Buffalo Public Schools invested millions in renovating Bennett, and the classrooms and corridors are bright and tidy. At the front of the school, three pairs of double doors open onto a vintage-style foyer with trophy cases rising from a black-and-cream-checked floor. Is this the Bennett you imagined?

•

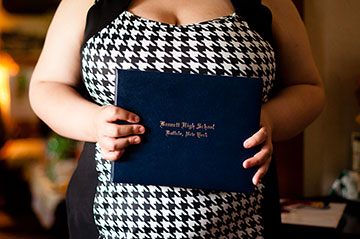

It’s the morning of graduation, Friday, June 21, a day that dawns blue and clear in a month where the forecast called for rain or thunderstorms nearly every day.

Beneath the towering ceiling of the Bennett High School auditorium, an audience of hundreds has gathered: seniors in caps and gowns, and their brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, grandparents and friends.

Cheyenne is at the podium, a red-and-blue tassel dangling in her eyes. Below the stage, in the first rows, are her classmates—the Class of 2013—the boys in blue and the girls in white robes that look silver under the darkened lights.

Cheyenne is giving her valedictory address. The words come quickly, one after another, an avalanche that she can’t stop. Later, she will cry, but for now, she is holding it together.

“It’s crucial that we don’t forget where we have come from,” she says, speaking to the young men and women who have been so much a part of her life over the past four years.

“Please consider the adversities and tribulations you have faced in your life thus far,” she says. “Remember what you learned from them, how to deal with them, and don’t allow repetition of these afflictions to hinder you from your forthcoming achievements.”

Cheyenne, 18, is the youngest of six siblings: herself, a half-sister, and four full sisters. Her father is William Franklin Jr., 60, a sergeant in the safety unit at the Buffalo Psychiatric Center. Her mother and William’s wife is Mary Ketter, 58, a woman of formidable stature and fierce opinions who believes that “Nobody owes you anything. You have to earn it.”

When her children were young, “They saw us work like dogs all the time, and [we] didn’t bitch about it. That was just what life was,” Mary said.

She and William worked for minimum wage when they had to. Both endured layoffs. Mary started as a security officer, rose to become a chief in the male-dominated profession, and then studied to become a nurse when her employer outsourced her position, she said.

They raised five daughters, sent them all to college, renovated a house on a quiet, tree-lined street in Buffalo’s University District and believe that work and education are the best way forward in an often unkind world. They are the kind of parents who wonder why schools send suspended children home. Doesn’t that just affirm that it’s okay to quit? It would be better, Mary said, to shut delinquents in a room with “someone who is the teacher from hell,” so they can be “force-taught.”

That regimental, business-first mentality rubbed off on the Ketter-Franklin kids.

Amber Ketter-Franklin, the oldest of Cheyenne’s four full siblings—all Bennett High alumni—said that even as a child, Cheyenne attacked homework assignments with a special ferocity.

Amber, 31, used to help her little sister with assignments, and remembers how in grade school, “You could see physical frustration when she didn’t get it.” Cheyenne would erase mistakes from her papers furiously, or throw pencils.

“It was the end of the world,” Amber said.

Fourth grade, in particular, was a nightmare for Cheyenne. She was always heavy, and kids at school teased about her weight as well as her race (she is mixed). Her teacher didn’t think much of her, she remembers, and her marks were low.

All that changed in fifth grade, with a teacher named Mrs. Connors.

“When I would get frustrated with work, she’d kind of sit there with me, and instead of giving me the answer, she’d be like, ‘You have this answer in your mind. You know you do,’” Cheyenne said.

“You’re not dumb,” Cheyenne remembers Mrs. Connors telling her.

Cheyenne insists that she is no smarter than anyone else, that she has no gift or genius her classmates lack. She was Bennett’s 2013 valedictorian, she says, because she studied, paid attention in school, turned in homework on time and asked questions when a problem stumped her. She often put more pressure on herself than her teachers did.

At Bennett, Cheyenne has watched friends and acquaintances make one bad decision after another: clowning off in school, experimenting with drugs, having unprotected sex. It’s sad to see, all those lives spinning off in the wrong direction. Some girls she knows have gotten pregnant twice.

Cheyenne shielded herself from it, mostly, because what else could she do? She surrounded herself with friends who were responsible. Despite Bennett’s reputation, it wasn’t hard to stay out of trouble, she said. The fights she heard about were usually between students who had a personal quarrel: girls trading blows over a boy, for example. Just keep your distance, don’t be impressionable, and you’ll be fine.

One experience that haunts Cheyenne, however, was watching a close friend, a boy she had known since fourth grade, lose direction. He was a good kid, she said, a talented artist with a brilliant mind. He didn’t struggle in class. But their junior year, he deliberately stopped paying attention, she said. He started drinking alcohol, smoking pot and skipping school to play basketball to fit in with new friends.

She still wonders about it sometimes, why he gave up so much for seemingly so little. He was never mean or malicious to her, but “I felt like he just ruined his future for himself,” she said.

“I almost feel at fault because I felt I should have kept him out of that track, and it makes me a little discouraged,” Cheyenne said. “If you want a poster boy for how your past doesn’t mean anything with your present, it would have been him; he had a bad upbringing and he always rose above it.”

She doesn’t like to think about it: the wasted potential, the life thrown away. She has always believed that every one of her classmates is capable of great things. Her father, William, remembers attending a parent-teacher meeting many years ago and discovering that his daughter was tutoring her classmates, free of charge, a practice she continued at Bennett.

“Driven,” he laughs. That’s how he would describe his daughter. “Giving” is another good word, he said.

•

Whatever image you have in your mind of what Bennett High School is like, erase it for a moment and consider Cheyenne: introspective, analytical, a composed young woman with a lion’s mane of curly dark hair, bleached blonde on top. When she engages in conversation, she speaks with intensity, making eye contact through black, plastic glasses that frame her round face.

In her free time, Cheyenne watches wrestling and Supernatural, a TV show about a pair of brothers who stalk monsters, demons and all variety of paranormal villains. She also likes video games. Tomb Raider and Asassin’s Creed are favorites that she plays on an Xbox 360 that she saved her allowance to buy.

She is, in summary, your average teenager, and her biggest problems in high school were the ones that adolescents everywhere face: fitting in and trying to figure out what kind of person she wanted to be.

As a freshman, she struck faculty members as alert and bookish—the “valedictorian-type,” as one of her teachers, Barb Trietley, put it.

Navigating Bennett’s social scene was more confusing. Cheyenne preferred homework to loud parties, and peers would sometimes ask for help in class and then ignore her after school. Their attitude seemed to be, “She’s good enough to teach them, but not good enough to call on the phone later on and ask if she wanted to see a movie,” her mother, Mary, said.

Cheyenne also struggled with being part of Bennett’s business academy. She loved medicine and anatomy, and couldn’t see how marketing and accounting fit in with her dream of working in health care. She would “complain and complain” about it, Trietley said, amused at the memory.

Four years later, Cheyenne is entering the University at Buffalo to study business. She credits Trietley and Tracie Batcho, two favorite teachers, with pressing her to stick with the field.

Batcho ran her classroom like an enterprise. Words like “stupid,” “idiot,” and “shut up” were not allowed—not in interactions with Batcho, and not in conversations between students. She edited people’s grammar as they talked, and soon the teenagers followed suit and started correcting each other. She taught the kids how to write a résumé.

Under Batcho and Trietley’s watch, Cheyenne stopped grumbling and discovered that she actually liked business, and that good management skills would help in any profession.

Her senior year in Batcho’s class, she acted as CEO of Distinguished Desserts, a mock organic bakery that she and her friends ran as part of a virtual enterprise class. They crafted cupcakes and pies from cement, and lugged the pastries to New York City, where they displayed their wares at a summit with other schools.

Cheyenne also traveled to California this spring to represent Bennett—and Buffalo—at the DECA International Career Development Conference. With Trietley as her chaperone, Cheyenne placed ninth in a tournament that quizzed students on principles of business management and administration.

The adversaries she vanquished included teens from Catholic and suburban schools, young people who, according to common wisdom, should have bested her. She also managed to sequester her nerves and make conversation with kids from other cities and states.

Recounting how Cheyenne worked the room, Trietley marveled at how much Cheyenne has matured. The Cheyenne that Trietley knew as a freshman would not have had the guts or confidence to mingle in a crowd with such ease.

It took time, but Cheyenne has stopped fretting so much about what other people think, Batcho said.

In the end, it was Cheyenne’s core character that earned her the admiration of classmates, Batcho said: her lack of pretention, her refusal to see herself as better than others. By graduation, Cheyenne had befriended students from varied social circles, including underclassmen, athletes, academics, and kids who struggled in school and requested a dose of her coaching before tests.

“They respect her because she respects them,” Batcho said.

As for Cheyenne, she has come to see herself as “more than just a brain,” Batcho said. “She defines herself. Other people can’t define her.”

•

Cheyenne’s grade point average at Bennett was a 97.67 through the middle of her senior year. Her lowest marks were a pair of 90s in P.E.

But her performance on the SAT was mediocre. Out of 800 in each category, she got 610 in reading, 520 in math, and 590 in writing.

Some people would look at these unexceptional scores and say that Bennett has low standards—that the A’s on Cheyenne’s report card wouldn’t be A’s at another school. One thing is certainly true: Going to Bennett, Cheyenne had far less access to Advanced Placement courses than students at many higher-ranked institutions. Faced with limited choices, she ended up not taking any at all.

Would Cheyenne have done better, academically, if she hadn’t gone to Bennett? It’s impossible to know.

Her mother, Mary, says if money weren’t a factor, she would have sent all of her kids to Catholic schools.

Mary isn’t sorry that her children ended up in the public system. She met many wonderful teachers, and each of her daughters did well, graduated and went to college. Reading too much into Cheyenne’s SAT’s may be a mistake; she scored high enough on her New York State Regents Exams to earn an Advanced Regents diploma, and bested challengers from ritzier institutions to get that DECA award.

Mary just wishes her kids would have had the chance to attend a high school where students were more focused, and families more involved. It still astounds her how little some moms and dads seem to care about their children’s education. She noted instances where kids have been swearing at teachers, “and the parent’s there defending them instead of kicking their ass.”

“Why do I only see 30 people on a parents’ night, wandering the halls like lost souls?” she said.

Despite her tough edge, Mary is one of the kindest people you’ll ever meet, her husband, William, says. The Ketter-Franklins have opened their home to several teens from other families over the years.

That includes Cheyenne’s close friend from Bennett, Breone. The 17-year-old had lost her mother in 2012. Her father wasn’t in her life, so she moved in first with her 26-year-old niece, and then with the Ketter-Franklins this spring.

In the months following her mother’s death, Bennett was Breone’s family—Ms. Batcho, who talked Breone through her troubles, and Cheyenne, who stood by Breone like a sister.

Teachers and classmates spoke hopefully of the future, made Breone laugh and helped her realize that she didn’t want, in her words, to “get stuck.” She has seen relatives wrestle with addiction—marijuana, cocaine, OxyContin—and struggle to make the rent. It’s not the life her mother would have wanted for her, and the folks at Bennett reminded her of that, she said.

Stories like these are what make Bennett such a special place, Cheyenne said. She has seen classmates falter, but she has also watched some awesome, life-changing stories unfold. She lost one best friend—the boy who abandoned his ambitions and dropped out—and made another—Breone, who has survived so much.

At Bennett, Cheyenne has seen the best and worst of the world. Her classmates’ stories will stay with her wherever she goes. She will always believe in the ability of the underdog to win—to prove people wrong. She knows it can happen, because she saw it happen every day at Bennett.

•

“Our lives are just starting, and now is the time to reach heights greater than ever. Now is the time when you should put forth the most effort, to believe in yourself as much as you possibly can,” Cheyenne says, reading from her valedictory address.

The auditorium, rowdy earlier with screams—“JAZMON!!!” one woman blasted in a typically ear-splitting decibel—is now quiet.

About 10 rows from the front, in seats kissing the center aisle, are Cheyenne’s parents: William, in a light blue polo, khakis and shined black shoes, and Mary, in a tan-and-turquoise paisley dress, with glittering russet hoops hanging from her ears. Amber, the older sister, who used to take little Cheyenne to the library on Thursday afternoons, is also there.

It’s an emotional moment for the family. How to describe the feeling of seeing the last of a flock of children graduate from high school? All that effort, all those years of working hard and making sure the kids did the same—few words could capture the feeling.

Cheyenne will miss Bennett: her classmates, all the fun she had here, and everything she learned. Looking back, she will remember the good times—meeting Breone, Ms. Batcho and Ms. Trietley—and the bad—slogging through her junior year, when she got rid of her lunch period to take a course in computer applications, played volleyball, sprained her ankle, and generally overwhelmed herself by trying to do too much.

In these hallways, she made laughed, cried, challenged herself, landed her first job (an internship with the credit union on campus), and discovered how much she was capable of accomplishing.

But, as she reminded her classmates in her graduation speech, this is only the beginning.

As Cheyenne finished her valedictory address, the audience clapped and cheered. The Class of 2013 stood, turned to face their loved ones and sang the school song one last time. Then it was time to go—to say goodbye. One by one, the graduates marched down the aisle of the auditorium and into the foyer, spilling out of the school’s double doors in a colorful tide of balloons, flashing cameras, hugs, tears, laughter, kisses, shimmering tassels and four year’s worth of memories.

As they made their exit, the seniors walked beneath a banner bearing Bennett High School’s Latin motto, “Optima Futura.” The translation: “The Best Is Yet to Be.

Charlotte Hsu is a freelance contributor to Artvoice. Though she completed this story as an independent project, she works full-time at the University at Buffalo, where she helps publicize programs including a science education partnership that is active at Bennett.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n31 (Week of Thursday, August 1) > Bennett's Best This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue