Next story: Peace Bridge Expansion - Deja Vu With an Episcopalian Twist

Jungle Bungles

by Mason Winfield

Summer 1813: The Guerrilla War

The summer of 1813 was a hot one on the west side of the Big River. Since late May the Americans had held Fort George and a perimeter around it in today’s Niagara-on-the-Lake. But Canadian guerrillas, British paramilitaries, and the Empire’s Native allies drove them crazy. The informal war-inside-the-war may be the most neglected side of the Niagara conflict.

It needs to be explained that except for cleared areas around farms, towns, or major highways, the Niagara Frontier in 1813 was almost impenetrably wooded. Areas between armies or outside forts needed to be constantly surveilled by groups of fighting spies called “pickets.” Both sides relied upon them, only one of the day’s conventions that may seem to defy logic to readers who are not 1812 specialists. When these “eyes and ears” of an army met in the woods, ambush—the number one tactic of forest fighting from Teutoberg to the Tet Offensive—and close-quarters combat was the rule, using swords, tomahawks, clubs, and even knives. Knives? Now this defies logic to me.

Halfway house personnel tell you that when someone comes at you with a knife, the general rule is to get something bigger. (A mop. A chair. I’d be good with a tennis racket.) Law people tell you that, inside six feet, they’d much rather the guy had a gun. (You might not get shot. You will get cut.) Martial artists tell you that in close combat, the shorter weapon can be better. And in the era of slow-loading guns, the only weapon that always works is the one without the trigger. Two incidents stand out from the summer of 1813.

When the British fled Fort George under the American assault in late May, they buried a cache of medical supplies on the farm of Casper Corus by Two Mile Creek in today’s Niagara-on-the-Lake. On July 8 they sent a handful of men back to retrieve it. As they dug, their escorts—a large number of Western Great Lakes Native Americans under a chief remembered only as “Blackbird”—lurked in the dense woods. A 50-man American force blundered in. Thirty-five prisoners were gruesomely killed. “Message massacres” are not new to war, but what befell this small party was outrageous. To their credit, the Canadian whites (probably including the young William Hamilton Merritt, future builder of the Welland Canal) did all they could to stop the atrocity, and the local Mohawk would surely have listened. But Blackbird and his buddies had no local connections. Their debt was to the Empire, and it appreciated them as intimidators. They believed that the cause of holding their homelands could still be won. (By the end of the American Revolution the New York Iroquois had seen otherwise.) Like so much else in this war, Two Miles’ Creek would have its reverberations, one led by militia colonel and Buffalo doctor Cyrenius Chapin (1769-1838), fresh off an adventure of his own.

Chapin was among the Americans taken prisoner at the British victory of Beaver Dams (June 25) and, with half his riding Robin Hoods, the “Forty Thieves,” was held at Burlington Heights. On July 12, they were shipped off toward Kingston, Ontario, under a strong guard in two open boats, and Chapin and his proverbial cutpurses made a Hollywood-style escape that begs for development. Another day.

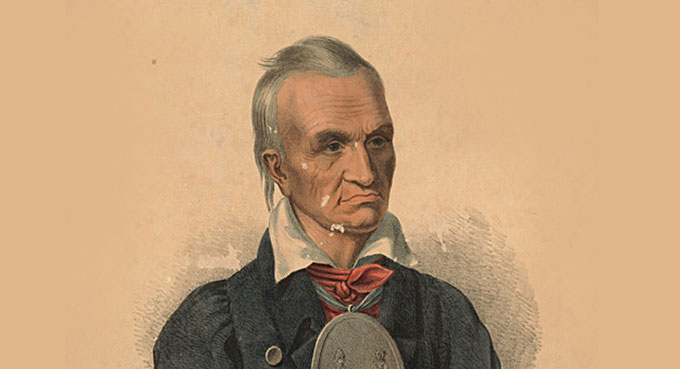

By August, Chapin was back at Fort George and ready to get some more war in. Much-admired by the Seneca who knew him as “the Great Medicine Man,” Dr. Chapin was approached by Red Jacket, Farmer’s Brother, Young Cornplanter, and their white buddy “Cattaraugus” Hank Johnson with a plan to strike at the guerrillas who had bedeviled them all summer. On August 17, 500 volunteers, regular soldiers, and Seneca snuck out of the Fort, looped into the woods outside it, ringed a grove stocked with tormentors, and settled scores. (They killed 75 men and took 16 prisoners.)

When we look at the loss of life in these two obscure incidents and compare it to the reports of the famous battles, we get a new picture of the Niagara war. For instance, Wikipedia’s article on the 1812 battle of Queenston Heights numbers 121 deaths. At the end of a single day (August 21, 1814), British General Gordon Drummond handled scalps brought him by his Native allies, counted corpses being carried into Fort Erie, and judged that up to 50 Americans had been killed after one untitled clash. We’ve seen over a hundred deaths among the losers in the two incidents above from the summer of 1813. If I believed there was an accurate way of measuring the matter, I would be shocked to find that the Niagara’s famous battles—Black Rock, Chippawa, Lundy’s Lane—dealt more violent deaths than the three-year cycle of rumbles remembered only in the officers’ reports and the footnotes of the thickest texts.

The founder of Haunted History Ghost Walks, Inc., Mason Winfield is the author of 10 books including Ghosts of 1812 (2009), published by Western New York Wares.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n31 (Week of Thursday, August 1) > Jungle Bungles This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue