Next story: Examining the Life of Mabel Dodge Luhan at the C. G. Jung Center

Dana Hatchett at the C. G. Jung Center

by Kevin Kegler

It Ain’t What You See, It’s the Way That You See It

The morning before I started this review, I was wide awake, 3am, and unable to sleep. Compelled to get out of bed, I was drawn to the bright light coming from a window on the west side of my house. Still drowsy from sleep, I looked up at the full moon and my mind was shocked into clarity by what I saw. This was a moon unlike any I had ever seen. Big, beautiful, and haloed in violet. I have seen the moon in all its phases, in various weather conditions, from several continents, but never like this. It was stunning. So much so, that I was about to go into an adjacent room to wake my daughter to see this never-before-seen moon. As I was turning, my eye caught the neighbor’s porch light. Very weird, that light also had a halo with a violet edge. At that instant I knew it wasn’t the moon; it was me, my eyes, my lens that created the halo. With a brief experiment of blinking my sleepy eyes, I realized what I saw was delivered not by the cosmos or the atmosphere, but just a thin film on my eye brought on by a cold. It was to be a short-lived seemingly divine vision.

This revelation, seeing the surreal moon with altered vision, on the morning of my third visit to Dana Hatchett’s exhibit, helped me to see another side of what he was doing. My early morning sighting set me on the path that day to look at his art in a new way, allowing me to see something I hadn’t seen before.

Whether Hatchett’s intention or my interpretation, I found this work challenging. It hasn’t the formal qualities that create a harmonious whole: In other words, it is not a beautiful picture. It does not carry the narrative to give me easy conceptual access, not a hint of representation, nor does it possess the irony that’s prevalent in much of contemporary art. This body of work was tough. How do we make intellectual choices or intuitive leaps to find meaning in contemporary art? Whether it jibes with the artist’s focus or not, we want to know what the work means. After all, it was made to elicit something, large or small, deep or trite.

I have watched Hatchett over the last decade move from his experiential poured paintings to his cerebral landscape paintings, to his mystical landscape drawings, and now to this: mixed media constructions, hung like paintings. I needed a new approach to read and qualify this work. I knew where he had been. We have spoken over the years about his process, his research, and his deep connection to material and technique. So it was a curious experience to see this series and realize I needed to find a new way to think about it. His prior paintings and drawings, by which I have been moved and delighted, followed the rigor and delivery of an intelligent and talented artist, and this new work was no exception. Those who know him know of his consistent tenacity in the pursuit of communicating something beyond the surface.

So it is with this informed respect in mind that I take the next step in responding to the collection currently on view at the C. G. Jung Center.

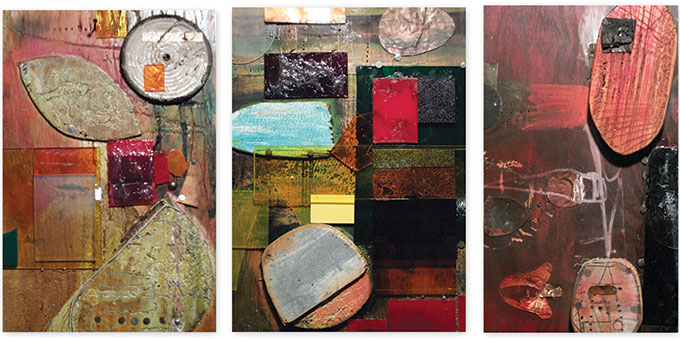

These pieces on first viewing appear spontaneous and chaotic, neither finely crafted nor balanced. But considered more thoroughly and more intimately, the compositions, while in fact chaotic, are not spontaneous. They look to be meticulously evolved to create a work that the artist has meditated on. Each component of each construction can hold its own in singular, functioning within the group of parts but independent at the same time. They feel like moments in a continuum: each distinct, but held together in time and space by simply documenting each “now” that makes up the whole.

Walking through the show, taking in each work, it came to me that these constructions are about the parts. And these parts, pieces of acrylic sheet, mundane pieces of scrap wood sanded round, and veils of color, require a focused assessment. Dominated by brightly colored pieces of transparent plastic, the work is about what we look through. Not what lies behind the lens but the lens itself. It is always through a lens that we perceive, and through which we create our corporeal world. It is our own personal lens that we look through that creates the world we believe in. The really real is only our real.

The intentions of the constructions are not about the formal relationships, the craftsmanship, or mastery of materials. Rather the opposite—a sense of casual relationships pervades this show. There is no attempt to hide glue or paint or fasteners. In fact, those actual means of assembling, that artists so often choose to hide, are left for the viewer to ponder, front and center. Hatchett goes so far as to utilize large-head roofing nails to hold down fabric and assorted detritus. These constructions are all built off a plywood base simply cut into rectangles: some with basic stick frames, some using only the plywood edge. The colored acrylic sheets are either cut rectangles or basic organic shapes, unrefined and unceremoniously applied to the wooden base. Some of the work has surface marks and patterns knocked into them. Additionally there are various bits and pieces of found material.

It was on the third viewing, while sitting in the east gallery of the Jung Center, that I glanced into the middle room where Rite is hung. At that moment I was able to experience the work in a way that I couldn’t while up close, where I scrutinized every bit and speck for an underlying unity. It was this distance of 25 feet, this lens with a new perspective through the warm light of the gallery that allowed me to find meaning in Rite. From that distance, the colors, reflected and refracted, glowing as if trapped behind the acrylic, unified into a whole piece. I experienced a richness of congruent colors playing off each other in the same piece that up close, I found to be incongruent pieces in the composition, acting as individual endpoints. It was the palette of colored light that emerged from a rich dark ground that gave this work a strong resemblance to that of Kurt Schwitters, the master German collage artist. I would challenge the audience to experience the work from various perspectives to understand my comparison, which may not be initially apparent, but which can broaden the range of possible interpretations. That piece has the capacity to become a collection of jewels. Or not, depending on your lens.

Additionally, it was this new view that gave me insight into the end game for this body of work. By countering an aesthetic of intricate beauty, the artist chooses compositions that overtly struggle with cohesiveness. Most of the pieces in this exhibit have a fragmented feel when viewed in a close, comfortable viewing range for small to medium sized artwork. When viewed from a different perspective, perhaps in the form of physical distance, those works can unify and deliver their complexity and relevance.

Hatchett is not presenting pretty. He is not presenting shallow or easy. What he is giving us is the chance to go deeper, beyond the surface. The connection of the work to a spiritual process, not unlike many artists’ processes, comes through in this collection. In keeping with those dark and ethereal landscapes that Hatchett has painted over the years, these constructions offer investigations beyond the physical, into a unique place for everyone willing to give them time.

If we realize that we approach art, as we do life, with our own personal lens and in turn realize that the lens can be changed, we open our world to untold possibilities. As the printer Amos Kennedy proclaims through his work and actions, “Proceed and Be Bold.” Discard your old lenses; jump in, the water will wake you.

Dane Hatchett will deliver an artist talk on this exhibit at the C. G. Jung Center, First Friday, October 4 at 7pm.

Kevin Kegler is a fisherman and beekeeper living in Buffalo. He is also a professor in the Visual and Performing Arts Department at Daemen College.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n40 (Week of Thursday, October 3) > Art Scene > Dana Hatchett at the C. G. Jung Center This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue