Trust No One

by Woody Brown

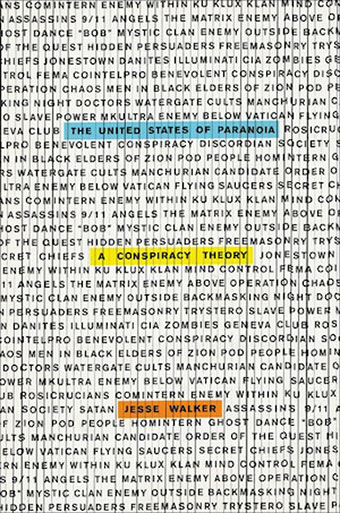

The United States of Paranoia

by Jesse Walker

HarperCollins, 2013

Did you know that Cincinnati, Ohio was named after the Society of the Cincinnati, “an aristocratic military order” formed in America in the late 18th century “that hoped to establish itself as a parallel government in each state”? Did you know that the birthers’ suspicion that President Obama was born in Kenya dates back to “the 2008 Democratic primaries, when Hillary Clinton’s supporters started wishing for a miracle that would remove her chief rival for the nomination”? Did you know that the CIA conducted a program called MKULTRA that involved dosing unwitting American and Canadian citizens with LSD for extended periods of time?

These are only three of the hundreds of fascinating facts contained in The United States of Paranoia, Jesse Walker’s even-handed and unbelievably well researched history of conspiracy theories in America. Walker’s interest is not in proving or disproving certain theories, but in examining the role paranoia has played in American life. This book achieves that goal with the sort of thoughtful honesty we find in the best historical writing.

Walker begins his investigation in 17th-century New England. The half-hidden specter of the Indian gave rise to countless fantasies of imminent danger and impurity among the colonists. The alleged assassination of John Sassamon, a Christian convert from the Massachuset Tribe who informed the colonists of the threat posed by Wampanoag leader Philip, and the subsequent execution of his alleged assassins sparked King Philip’s War, “a war more lethal, in proportion to population, than any other conflict involving either the English colonies or the independent United States.”

Walker insists on examining every source that might complicate the generally accepted version of the events, a narrative that eventually appears dubious at best. Along the way, we learn countless fascinating bits of information that modify our assumptions about American history. The opposition of the English and the Indians seems quite a bit less certain when we recall that “Harvard’s 1650 charter described it as a place for ‘the education of English and Indian youth,’” doesn’t it?

Walker formalizes the paranoid fantasy with four categories: the Enemy Above, the Enemy Below, the Enemy Within, and the Enemy Outside. Ample examples of each abound: the basically unfounded fantasy that Osama bin Laden was a “terrorist CEO” (Enemy Outside); the violent fear of Shakers in the 18th century (Enemy Within); the fear of black Americans throughout essentially all of American history (Enemy Below); the obsession with the Illuminati in all its varied foggy forms (Enemy Above). This formalization gives structure to Walker’s investigation and allows him to examine the psychological tendencies that motivate “the paranoid style.” The categories also illuminate the scandals and suspicions of American politics in the present day. As we follow Walker, we find that the ostensibly unique fears we have now (e.g. of Al Qaeda as a “global terrorist network”) we have had many times before with different proper nouns.

Walker is unafraid to call a racist spade a spade, especially when it comes to the CIA’s persecution of black activists during the 1960s. In one particularly bizarre example, we learn of a CIA plot to incite paranoia within groups like the Black Panthers by disseminating “a series of anonymous messages with a mystical connotation” that mean nothing. The next page shows a scanned image of one of the messages: a drawing of a beetle with the text “BEWARE! THE SIBERIAN BEETLE.” Many conspiracy theories can finally be reduced to a deep fear of the otherness presented by people who appear different from the enterprising white American male.

There is a greater metaphor here, though, the presence of which Walker suggests but shies away from elucidating fully. The apparent differences between the four categories belie their deeper commonality: a human need to construct a narrative out of otherwise unrelated events. Narrativization grants history a meaning whose striking convenience hides the unsettling possibility that some things happen for no reason at all. It is easier to believe that Jared Lee Loughner shot Gabrielle Giffords because of the right wing’s inflammatory rhetoric, not because he was a deeply mentally ill man who “advocated an ‘infinite source of currency,’ warned that the government is using grammar to control people’s minds, and expressed what one journalist described delicately as “indecipherable theories about the calendar date.’” It is easier to say something is always the fault of a disembodied evil intention than to recognize that each of us has the potential for great good and perhaps even greater evil. We write our own secret desire onto the mouths of others.

But we certainly cannot fault Walker for remaining committed to his task as a historian. His is the work of a researcher and a scholar, work for which he clearly has a passion. The United States of Paranoia contains such a multitude of citations (Walker has apparently read in full everything from Increase Mather’s 1677 Relation of the Troubles Which Have Happened in New England by Reason of the Indians There to the heavily redacted CIA FOIA revelations) that the reader has no choice but to conclude that no stone has been left unturned. He is also impressively well versed in American film and fiction of the last 150 years. And he can be pretty funny too, as in his brilliant alternate ending to The Matrix: “My fantasy for how the trilogy should have concluded: After learning that every level of reality is just another matrix, Neo shrugs his shoulders and walks off the film set. A digital camera follows him across the street to a lecture hall, where a professor is denouncing metafiction and declaring postmodernism a literary dead end. Keanu’s cell rings: It’s his agent. We hear them chatting about how much they’re making from Matrix merchandise. Then the wall collapses and the cast of Blazing Saddles falls into the classroom, throwing pies.”

Informative, smart, and relentlessly interesting, The United States of Paranoia is worth more than one read. It is an indispensable reference in an age when a video on the internet can start a war.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n41 (Week of Thursday, October 10) > Trust No One This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue