Next story: 18th Annual Altars Exhibition at El Museo

Craft and Design on Exhibit at the Burchfield Penney Art Center

by Jack Foran

Undoing Genre

Two terrific exhibits installed cheek by jowl at the Burchfield Penney Art Center seem to raise the same question. About supposed artistic categories. Genres. Do they mean anything at all?

The two exhibits are the Art in Craft biennial exhibit and the current Charles Burchfield exhibit, By Design. (I went to the gallery purposely to see the craft show, but couldn’t help having a look in also at the adjacent Charles Burchfield exhibit.)

The Charles Burchfield opens with a lovely and poignant vignette from one of his journals, about dissatisfaction with the work he was doing at the time and a conversation with his mother.

He was making a sketch of a petunia, and he wrote:

I remarked to mother that I was wearied of it, and she wondered why. I said I did not like to draw such things. She chided me for not knowing what I liked, and then I said I wanted to paint scenes, expecting a storm. She said, “Then you’re going to be an artist?” I said, “yes.” She said, “Here I thought you were going to be a designer,” but smiled and kissed me.

Burchfield studied for a time at the National Academy of Design in New York City, but left there unsatisfied with the work, but then soon after began to develop what the exhibit explanatory information calls his “lexicon of abstract pictographs,” which is to say, “design” elements that became the core symbolic system of his paintings for the rest of his life. The means by which he expressed his unique vitalist vision.

Art, design, not much of a real distinction.

Much the same for art and craft. What’s the difference?

Artist/craftsman Stephen Saracino, one of the jurors of the craft exhibit, gets into just this topic in his statement. “What, after all, is craft?” he says. “To most, ‘craft’ suggests some soft of an object that is hand-made. What form of art isn’t?”

(The answer, in brief, conceptual art. Art that is art because an artist declared it art. Duchamp didn’t make the urinal he so famously exhibited.)

Saracino is a metalsmith. Trained as a jeweler. Further on in his statement he considers the idea of utilitarian as a possible criterion for craft, jewelry usually being considered utilitarian. Something to be worn, to be used. But he considers his jewelry works—like all his artistic production—to have “evolved well beyond…even a vestige of utilitarian function.”

This is true as well of practically all the supposed jewelry items in the show. They’re beautiful, but not necessarily to be worn. Not fundamentally utilitarian. And as well of the non-jewelry items in the show, only a handful of which are even conceivably utilitarian. In fact, in most cases, pointedly non-utilitarian. Which may be just the point.

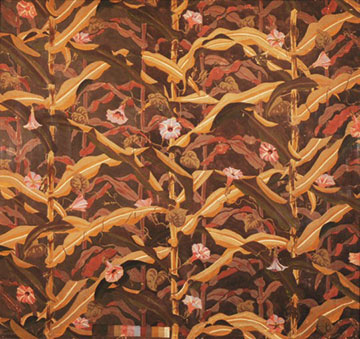

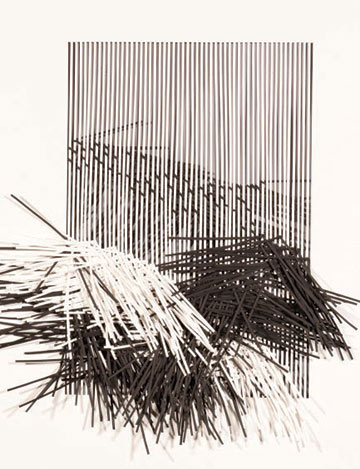

“Evolved well beyond,” Saracino says. The other jurors, in their statements—trying to say just what is craft art, in particular their own craft art—get at much the same idea. Mixed-media artist Robert Wood talks about the traditional “functional” aspect of craft art and how of late “artists and designers have referenced this historical aspect…and at the same time pushed beyond the normal conventions of the medium, challenging established traditions and assumptions about art and craft…a fundamental shift toward a more narrative, intellectual, and conceptual framework…” Nancy Belfer talks about her research into historical textile traditions and her experiments in adapting historical methods to produce her fiber-based works, creating “a kind of internal dialogue between the idea and the means…” Sunhwa Kim talks about adapting traditional Korean/Japanese lacquer techniques for her contemporary design woodwork domestic furniture creations. Examples of the jurors’ craft works are on display along with the juried works.

Craft art, on the one hand, a rejoinder to conceptual art—the emphasis still on the hand-made character—but conceptual itself in a different way.

Do genres mean anything? Not really, I think. The idea went back to the Greeks. Epic poetry was supposedly more exalted than tragic dramatic poetry, which was higher on the artistic scale than lyric. Forget about comic dramatic. Forget about prose. All the sheerest nonsense, that we still cling to, in whole or substantial remnant. We talk about these things as if they were real.

The Charles Burchfield show continues through December 29. The craft show through January 19. See more in this week's Back Page section.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n46 (Week of Thursday, November 14) > Art Scene > Craft and Design on Exhibit at the Burchfield Penney Art Center This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue