Next story: Paintings by Rodney Taylor at UB Center for the Arts

Paintings by Bruce Adams at the Castellani Art Museum

by Jack Foran

Myths and Lies

Back in 2004, when Bruce Adams participated in art photographer Spencer Tunick’s project in the Central Terminal involving naked multitudes, he had a revelation. Looking around at the sea of naked bodies, he said, it struck him: Not one of them was beautiful. The revelation prepared him for making his own art, a major exhibit of which is currently on show at the Castellani Art Museum at Niagara University. Paintings of naked bodies aplenty, many of them distinctly not beautiful. (The bodies, not the paintings.)

Not beautiful not with respect to true beauty, inner beauty, but outer beauty, beauty in a properly vulgar sense. The sense of beauty artist Cindy Sherman, whose work is on show in an adjoining room, intended when she complained of how “whenever there is a female figure, she’s always beautiful.” In representations in domains from art to fashion. The Sherman quote is from a label on one of her works on display. Her art, of course, is much about undercutting the vulgar beauty idea.

In a brief talk at the opening, Adams jokingly noted several connections and comparisons between himself and Sherman. For example, he said, he and Cindy were art students at Buffalo State College at the same time, but added that he never actually met her during that time.

What he didn’t say about connections and comparisons between himself and Sherman was how their major aesthetic concerns—including copious sociopolitical concerns—over the years were strikingly similar. Bodies, body images, the history of art, the real and ideal, true and false, and in his case in particular, the nude, the art history traditional subject matter most illustrating and incorporating all of the above concerns. Gender and power, she as basically a photographer and feminist, he as basically a painter and unabashedly masculine, but without the often associated connotation of chauvinist. The preference for the real over the ideal, true over false, discomfits chauvinism.

The title of Adams’s exhibit is Myths and Lies. Throughout Western art history, mythological and related allegorical art was typically nude art. Stories about the gods. And so, typically also, idealized nudes. For Adams, nudes evoke mythological and allegorical art, the old stories about the gods, but to make the stories relevant to contemporary concerns—the concerns noted above—he unidealizes the imagery. Contemporary concerns relate to an unidealized world. No more gods.

(Another way to look at all of this, in Western art history, mythological art has been a hook to hang nudes on. For Adams, nudes are a hook to hang old myth stories on, which he updates by unidealizing the nudes.)

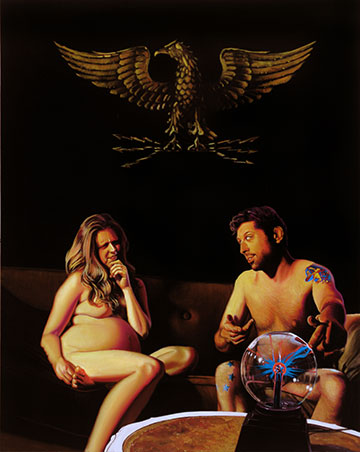

One work shows Zeus and Semele and a little plasma ball static electricity toy, which Zeus seems to be explaining the operation of and/or touting the potency of to Semele, who seems dubious, skeptical, though to her ultimate peril. Semele was one of Zeus’s lovers, who burned to death in the flames of a sudden and unexpected manifestation of his powers, here equated to sexual powers. The sudden conflagration ploy was engineered by Hera, Zeus’s jealous wife (and sister).

In dying, Semele gave birth to the lesser but nonetheless formidable god Dionysius, not represented here in person but in the figure of one of his disciple satyrs, in outrageous feathery leggings and bearing a thyrsus.

Another of Zeus’s lovers, Leda—to unite with whom he disguised himself as a swan—is shown in two works painted at more than a dozen years’ interval, and in both cases featuring the swan, a plastic planter vessel of some sort. The Leda model changes in the interval, but not the swan. (The swan is also on view in a glass case.)

A painting of Helen, known as Helen of Troy—offspring of the union of Zeus and Leda—shows her updated in several ways from the godlike apparition seen on the Trojan battlements. By dint of some added years and flesh. Here more the actual mortal woman, a decade or so later, back home in Sparta with Menelaus. As well as by an array of modern battleships, barely visible in the background in black on black paint texture and sheen variations.

Nor is the Norse pantheon neglected. The goddess Gunnr, one of the Valkyries, the deities who oversee battlefields and decide who lives and who dies, is shown as a beefy rollerblader, and based on obvious word play on her name, apparently, apparently a kind of patron saint of the gun crazies, amid a décor of traced outline and black on black assault rifles.

The Bruce Adams exhibit continues through June 29. (The Cindy Sherman through July 20.)

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n18 (Week of Thursday, May 1) > Art Scene > Paintings by Bruce Adams at the Castellani Art Museum This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue