Highlights From the Canadian International Documentary Festival

by M. Faust

What's Up, Docs?

In the world of cinema, documentaries are to multiplex movies what fruits and vegetables are to cheeseburgers and pizza. Given your druthers, you may gravitate toward the immediate gratification of the latter. But once you get used to a diet of healthier fare, you may find yourself losing your taste for junk food.

OK, that’s a shaky metaphor. For one thing, there’s no lack of bad documentaries out there, many of them cluttering up those hundreds of cable channels you have to scroll through in search of entertainment. But good documentaries pull you in and deepen your involvement with the real world the way no digitally frosted superhero movie is likely to do. And there’s no better concentration of good documentaries than what you’ll find at Toronto’s Hot Docs every spring.

Formally known as the Canadian International Documentary Festival, Hot Docs has grown by leaps and bounds over the past dozen years. (Not unlike the rest of the city.) I attended regularly for the first half of the 2000s, but stopped going because it was becoming too successful: I was spending too much time on lines for movies that sold out before I got in.

I went back this year and I’m happy to report that the festival is much more user-friendly. Of the seven venues where the bulk of the screenings take place (this year over eleven days from April 24 through May 4), two of them are the ones that house most of the screenings for TIFF in September; the capacious Scotiabank Theater on Richmond Street West and the ultramodern TIFF Bell Lightbox, a few blocks away on King Street.

There’s also the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema, a 101-year-old theater that in recent decades served as a repertory theater known as much for its, shall we say, funky ambiance as for its eclectic programming. Beautifully restored, it is now one of the only theaters in the world that shows nothing but documentaries year round.

Like TIFF, Hot Docs is the festival where you want to launch your film, so programmers are able to pick from the cream of the crop. (That’s what makes the difference between a good film festival and a bad one, which in some instances exist only to collect submission fees from filmmakers desperate to get their work into anything called a “festival.”) Hot Docs audiences are engaged, respectful and appreciative, and up until the last two days every film I saw was followed by a Q&A with one or more of the filmmakers (documentaries always leave you with questions to ask).

What Not to Miss on Your Next Toronto Trip

I probably make the trip up the QEW to Toronto 10 or 12 times a year, and every time I do I swear the skyscape seems to have changed: less sky, more buildings. And the closer you get to downtown, the buildings get both denser and taller.

But even as Toronto seems hellbent to become the Tokyo of North America, many non-downtown neighborhoods are hanging onto their identities, or building new ones that utilize and maintain the city’s past. If your visits to our northern neighbor are in a rut of shopping and shows on Queen Street and Yonge, you are missing a lot of the city, all of it easily accessible by public transportation (the subway is fastest, but the streetcars give the better view).

There’s no better example than the area known as “The Junction,” centered on Dundas Street in the northwest part of Toronto. Once a separate village founded on native trading trails, it became a railroad center in the early 1900s which such a boisterous reputation that the sale of alcohol was banned. When the ban was lifted in 1998, it opened the doors to bars, restaurants, and the revitalization of the neighborhood. Appropriately, the signature business of the area is the sale of reclaimed furniture and architectural details—essentially scavenging what is good from otherwise decrepit old buildings. (All the dealers I spoke with here claim to make regular hunting trips to Buffalo.) An unhurried, walkable area with plenty of cafes, bakeries and one-of-a-kind shops, it has the funky vibe of Brooklyn before it got out of control. thejunctionbia.ca

On the eastern end of Toronto you’ll find the Gerrard India Bazaar, also known as Little India, which spans seven blocks of Gerrard Street East. The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is home to the largest South Asian population outside of the Indian subcontinent (in excess of half a million people). While they don’t inhabit any single area of the city, this strip gives them a cultural and shopping center that grew up around a moviehouse that showed Bollywood films. There’s plenty of art, clothing and textiles for sale and browsing, but even if that doesn’t interest you it’s a great place to eat, with (by my count) 18 restaurants offering every variety of cuisine from India (north and south), Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. It’s open all week, but a weekend visit gives you the full effect. gerrardindiabazaar.com

Toronto’s gay community is centered around Church Street, the first main strip to the east parallel to Yonge. Inevitably known as The Village, it’s an area rich in history (by all means check out the bronze statue of founder Alexander Wood on the northwest corner of Church and Wellesley). And from June 20 – 29 it will be on the world’s stage as the annual Toronto Pride festival pairs with the international WorldPride celebration, an enormous ten-day event (held in a different city every five years) that is expected to bring millions of international visitors to the city. worldpridetoronto.com

King Street West has become known as the city’s entertainment district, but by no means does it have a monopoly. There are so many fine arts organizations in a one-mile stretch of Bloor Street (the northern edge of downtown) between Bay and Bathust Streets, that they have recently formed a partnership called the Bloor Street Culture Corridor. Regular visitors are probably already familiar with the Royal Ontario Museum. But the dozen other venues range from fun (the Bata Shoe Museum) to tony (the Royal Conservatory, in a beautiful old building worth visiting even if you don’t have time for a concert). And of course all of Bloor West is one of Toronto’s most walkable streets, wherever you start and end your tour, from the upscale shopping in Yorkville to the Eastern European of the Bloor West Village.

My thanks to Tourism Toronto for expanding my knowledge (in between Hot Docs screenings) of a city I’ve been visiting for many years, and for putting me up at the lovely Hotel Le Germain on Mercer Street, right next door to one of my favorite places to visit, the Second City comedy club. One of two boutique hotels in Toronto run by Montreal’s Groupe Germain (that fellow riding his Vespa on King Street is manager Paul de la Durantaye shuttling to the other location at Maple Leaf Square), it is an impressively spacious oasis in the midst of one of the densest areas of the city—I’ve never seen corridors so wide or rooms so big in a hotel. I’m not one for describing the details of a room, so let this one suffice as an indicator of luxury: the heating/air conditioning system is completely silent. Yes, the room was comped for my stay. But I’ve been back on my own dime (not cheap, but rather less than any of Toronto’s five star hotels, and worth it for all the locations within walking distance I would otherwise be getting to by cab or subway.)

Of the two dozen or so films I saw (of the 197 presented), the one with the most lasting impact was The Overnighters. When the town of Williston, Utah becomes a center of the fracking boom, desperate men from all over the country flocked there hoping for high-paying jobs. Unskilled jobs exist, but usually with a waiting list, and many of these men spent their last dimes just to get here. Only Jay Reinke, pastor of the local Lutheran Church, is willing to help put them up while they wait, letting them either park their vehicles in the church lot or sleep in the pews.

But a lot of these men are so desperate because they have a few strikes against them, including felony records. The townspeople soon begin to resent them, and Pastor Reinke finds that acting as Christ would is hard for many reasons. While it seems to start out as an illustration of the need for charity, The Overnighters grows both more complex and more disturbing as people are brought down by the weight of their sins. It’s a movie that asks questions which can’t be answered but need to be discussed nonetheless.

An entirely different take on the dispossessed of the world is on view in the jaw-dropping Giuseppe Makes a Movie. Giuseppe Andrews is the auteur behind movies that I (and I dare say most of you) have never heard of, made in the trailer park where he lives and starring his neighbors: drug addicts, homeless drifters, elderly alcoholics. At first it appears that we’re watching another one of those documentaries about an inept filmmaker whose pretensions are offered for us to laugh at: he offers as his influences Pasolini, Herzog, Fassbinder and Bunuel. But Giuseppe, whose has made 30 movies and never spent more than 3 days on any of them, is the real deal, what Harmony Korine only wishes he could be. I don’t know if I would ever want to watch one of his DVDs from beginning to end, but for all the insanely improvised plots and general ugliness (which includes scatology that would embarrass a 14 year old boy with Tourettes), he believes in what he’s doing. Call him the G. G .Allin of independent cinema, and don’t say you weren’t warned.

Popular interest in documentaries started in the late 1980s with The Thin Blue Line, in which former detective Errol Morris uncovered evidence that a man had falsely been imprisoned for murder, and ever since then re-investigation of closed cases has become a genre unto itself. Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart looks at the 1991 case of the 22-year-old New Hampshire woman accused of hiring three teen-aged boys (one of them her lover) to kill her husband. The trial was the first to be broadcast wall-to-wall on television, attracting a national media frenzy. Whether or not the film convinces you of her innocence, it persuasively traces how her story was taken over and regurgitated by popular media to the point that a fair trial was effectively impossible.

Similarly, The Notorious Mr. Bout picks apart the media portrait of Viktor Bout, the Russian businessman who was captured by the US government and tried for illegal arms dealing. He was publicly vilified as “the merchant of death,” but filmmakers Tony Gerber and Maxim Pozdorovkin demonstrate that he was more likely simply a cog in an international industry for which the government needed a display case.

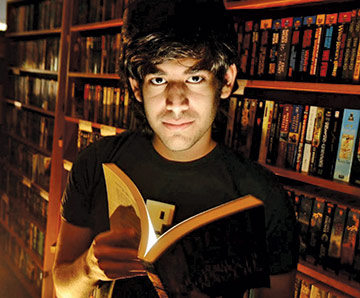

There’s little thought that computer prodigy Aaron Swartz, developer of RSS, Creative Commons and Reddit, was guilty of the crimes of which he was charged by Federal Prosecutors, at least not the way they were framed. It’s a complex case: suffice here to say that for downloading academic journals as a protest action he was charged with 11 violations of the archaic Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. After two years of being threatened with hard prison time of up to 35 years during which prosecutors reportedly refuse to budge, the 26-year-old killed himself. The Internet’s Own Boy veers a bit too often into hagiography, but it makes a strong case for freedom of information (Swartz could be the poster boy for net neutrality) and against a legislative system that is far too inflexible in a rapidly changing world.

Guilt is also not a question for the 260 prisoners at Russia’s Penal Colony 56, located in the middle of a forest the size of Germany, a seven hour drive from the nearest city. They are the worst of the worst, murderers who were mostly on death row in the 1990s when Russia abolished the death penalty (as almost all civilized countries have done). Given surprising access to a prison designed to be as remote as possible, the makers of The Condemned have crafted a powerful look at guilt from two perspectives: the society that has to deal with it, and the men who live with it. Whatever your perspective on issues of punishment, retribution and rehabilitation, this film will make you re-examine them.

Relations between the US and Russia may not be good at the moment, but they have been much, much worse, as Tim Toidze’s Khrushchev Does America points out. In 1959, Americans were primed to think that their imminent destruction could rest in the button finger of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. When he came here for a two-week public relations tour (apparently misreading an Eisenhower administration communication as an invitation), everyone involved was determined to turn it into a show of strength. That Khrushchev won that battle is clear as he insists on getting a chance to see the “real” America, turning stone-faced onlookers into amused fans and warming up the Cold War at least temporarily. At the post screening Q&A, Toidze, who edited hundreds of hours of footage for his feature, admitted that the likely US distributor (a cable network) has asked him to axe most of the film’s humor.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n21 (Week of Thursday, May 22) > Highlights From the Canadian International Documentary Festival This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue