Timothy Noble's Drawing Machine at the Burchfield Penney

by Jack Foran

Semi-Automatic

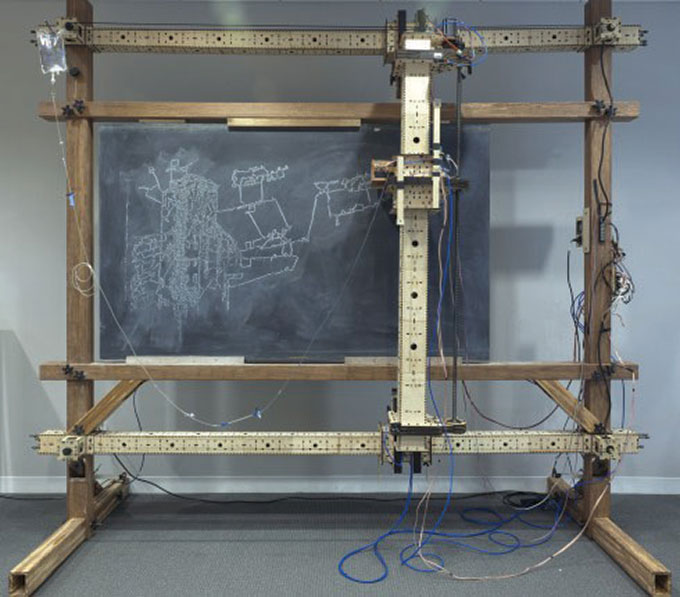

An exhibit by artist Tim Noble at the Burchfield Penney Art Center features an automaton drawing board programmed to produce outline facsimiles of some preliminary sketches artist Charles Burchfield made for a huge oil painting of Buffalo grain elevators.

The exhibit is “about labor,” Noble says in a statement, thinking of the countless hours he spent building and programming the elaborate mechanism—a work of art in its own right—but also of the work Burchfield performed on the sketches and finished painting, which clearly cost him some agony. He labored on the opus through most of the 1930s. In a note in a notebook from near the end of the decade, Burchfield writes: “The last three days on the Elevator picture—It has become a prison at last, from which I seek in vain to escape. I thought today I had come to the end, but at late afternoon, the foreground suddenly reveals itself as out of harmony with the rest…”

The 1938 painting and several preliminary sketches are on view, along with some apparatus-production versions of the sketches. And a huge sheet of row on row of minuscule numbers—x and y coordinates of instructions to the apparatus for making its versions. You watch the apparatus in herky-jerky operation, translating the x and y data into chalk lines on a blackboard. Without even squeaks.

In his statement, Noble points out that such robotic programmed mechanisms were invented as a way of disempowering labor forces, by taking over much of their skilled work functions, and in the process putting many workers out of work, decreasing labor force numbers and bargaining powers. (The invention of the grain elevator could be seen in a similar light. A lot of jobs disappeared. Not so much skilled jobs in that case, but jobs nonetheless.)

An implicit bottom line here seems to be that robots can’t do the kind of work Burchfield did. How many of us can? But we have to work to live. It’s not the actual millennium yet.

On the brighter side, Noble notes how presently artists and workers in a spectrum of commercial activities are adapting robotic technologies for their own uses, and inventing work not eliminating it. He’s a great case in point.

The Burchfield artworks are an exhibit in themselves. Two preliminary sketches, from 1931 and 1932, show rays of sunlight breaking through clouds, brightening the harbor scene. There’s none of this in the painting. It’s dismal dark overall, a prison-like enclosure of foreground harbor activity and inactivity, hemmed in by a near-distance array of towering elevators and smaller, stouter grain silos.

The 1931 sketch shows just the elevators and silos, the foreground undeveloped. The 1932 sketch shows more detail in the elevators and a foreground water view featuring a rough draft of a barge in broadside view. The finished painting shows the barge off to one side in end-on perspective, but in action, as it were, being loaded with or unloaded of grain cargo—loaded, it looks like, from the cloud of dust being created—via an off-vertical marine leg extension from the elevator main structure. A single worker, not doing much at the moment, oversees the operation.

It’s a rather anomalous work for Charles Burchfield, whose art is more characteristically about an irrepressible positive energy that informs every aspect of the natural and man-made environment. An Eden-like environment, in a way. This piece a conscious or unconscious meditation on the hard work of work—whether of the so-called artistic variety or the sweat of the brow prescribed in the Eden story.

The Tim Noble exhibit continues through May 25.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n3 (Week of Thursday, January 16) > Art Scene > Timothy Noble's Drawing Machine at the Burchfield Penney This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue