Next story: Worker Rights and the Minimum Wage

Photographic Memories

by Samantha Wulff

Dana Saylor-Furman: The Time Traveler

Remember being fascinated by old sepia toned or black-and-white photographs from the 1800s, 1920s, WWII or any time in the far flung past? Details like old signs; dresses, hats, horses, carriages, cars or weathered barns draw you to a world long gone. The close up of faces staring at you beckon you to them and for a moment you’re transported to another time and place. When that face belongs to your ancestor the experience becomes personal, and a paper photograph becomes a portal to your own past. In essence you become a time traveler to your great grandmother’s kitchen or your great-great grandfather’s farmland. Through painstaking research, digging up old photos, interviewing aged relatives, and visiting far away locations Dana Saylor-Furman has made many journeys to her personal past. She became so expert at the techniques needed she now she assists others interested in discovering their own past family.

“There have been numerous occasions when I could close my eyes and be there in that time,” Dana Saylor-Furman, president of genealogical and historical research business Old Time Roots said. “I have photographs of my great-grandmother on her farm and I can hear the crunch of the leaves and I can smell the crisp autumn air.”

Vera Crossman Hamel, Saylor’s great-grandmother passed away before Saylor reached her 10th birthday. However, the woman she had only known as a weak Alzheimer’s victim had much more to her story, which was revealed to Saylor through old photos found on the 1850’s family farm. Seeing her young, vibrant face and flowing dresses, Vera was not a wilting 80-something-year-old, she was an energetic, fun-loving young person, a mother, someone who carried around water buckets on a farm.

“She had a whole life and I only got to see the end of it,” Saylor said.

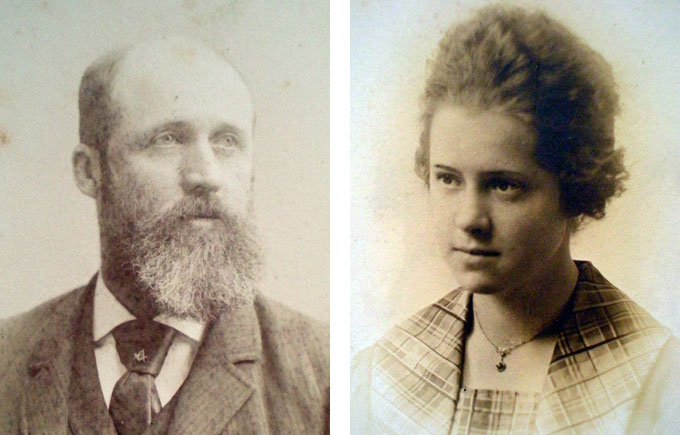

Within the farm’s collection of black-and-white snapshots of the past was a portrait of a mysterious bearded man. He was Civil War veteran Marcus Crossman, the original owner of the farm and Saylor’s great-great-great-grandfather.

“He is a figure that really captures me,” Saylor said. “When it’s your own family member and you’re looking at an image of them for the first time, it’s really thrilling. It’s fascinating. It makes you look at yourself differently. You think, ‘Do I look like them? How are we related? How are we connected?’”

Saylor came to find that Marcus was born in the 1840’s and had enlisted in the Civil War at age 17. In his older life, he became immersed in his community, serving as the town supervisor and building a high reputation.

“I can see similarities between him and other family members that are still alive,” she said. “I have this composite image of him as a young man. I picture him walking around, how tall he was, how he spoke…I think I pull some of that from the Civil War letters of his brother. I have a sense of the way they all spoke up there, the different vernacular, the things they would say. We want to look at an image of our ancestors and find ourselves in it…what similar struggles we can compare.”

The Civil War letters written by Saylor’s great-great-great uncle were addressed to his wife Matilda, and instead of delving into the brutality or loneliness of war, they focus on mundane, day-to-day things, her home-cooked meals, the farm and their children.

“One of the things he mentions in his letters to her is, ‘I can’t wait to taste those pancakes you were making.’ I thought about what a farm breakfast was like for him. They raised their own chickens, ate the eggs, and they probably churned the butter themselves.

“To think he was laying there in a tent somewhere in Virginia writing his letters with a fountain pen, scratching away on a reused piece of paper asking her to send money for socks, and missing her homemade farm breakfast—I can smell that smell. I can see that stove and the plank floors and the kids running around, and the roughness of the fabric they had to wear.”

Saylor has been doing historical research on properties and families under Old Time Roots Historic Research Services since 2008 and personally since 2006. Although she grew up with an inherited appreciation for history, the catalyst to start her own practice can be pinpointed to a specific trip in 2007, when she went to visit her great-grandfather’s homeland.

“I kept thinking about my mother’s side of the family,” she said. “I knew they were French Canadian. I didn’t really know a lot about where they lived, what they did, or who they were. I was generally interested but hadn’t dove into any research, yet.”

About a year into her research, Saylor and her husband decided to take the trip to France to immerse herself in the environment of those who came before her. Since her father’s side of the family was Italian and she didn’t have much knowledge of their past besides a surname and the approximate year they moved to America, she decided that a short drive to Italy would be a good supplement to the trip.

“I was like, ‘This is a perfect chance to learn more about myself, go to the place that my great-grandfather came over from,’” she said. “‘How cool would that be?’”

The town: Norma, a small town of less than 4,000 residents, approximately 30 miles southeast of Rome. The trip from where Saylor was staying in France would take about two hours by car.

“My friend had a car and loves driving in the crazy hilly mountain areas,” Saylor laughed. “So she was more than happy to take us.”

Walking through the town square, they came upon a group of old men playing cards. “Are there any Cappellettis here?” her friend asked.

"When it's your own family member and you're looking at an image of them for the first time, it's really thrilling. It's fascinating. It makes you look at yourself differently." - Dana Saylor-Furman

“The men kind of turned to each other and started to laugh,” Saylor recounted. “I thought, ‘Oh man, they just don’t even want me here.’ But what they said was, ‘Tanti, tanti, tanti Cappellettis.’: Many, many, many Cappellettis. Like, you’re basically in Cappellettiville.”

Saylor was directed to the church down the street from the square. Here, an elderly priest located a dusty record book from one of the shelves, flipped through its ancient pages and presented Saylor with the names of her ancestors.

“It was just one of those experiences that was life changing,” Saylor said. “I felt rooted in that place. It was the first time a place really had that kind of personal meaning.”

Upon her return home, Saylor was thirsty for knowledge, wanting to learn as much as she could about those who came before her. She was tenacious in her research to understand these lives that were connected to past worlds and also connected to her.

Shifting the focus back to her mother’s French Canadian side of the family, Saylor took a trip with her cousin and fellow historian to New York’s North Country, which is predominantly occupied by people of French decent. They interviewed family members in the area and that was really when Saylor felt that she learned to interview and find out what tactics work and which ones don’t.

“You have to know how people are in the area you’re going to,” she said. “In Northern New York, people are very nice, polite and helpful, but reserved. And even though I told them I was related to them, they were still slow to open up and talk until we had really broken the ice quite a bit. You also have to learn not to correct people’s longstanding beliefs about things because they’re just going to believe it. It really doesn’t matter what you tell them or what facts you show them.

“I was talking to my great-aunt about her mother,” Saylor said, “and she was saying, ‘Oh, she was this old [23] when she started having kids,’” Saylor corrected her, showing that she had her first child at 18, a fact that could be confirmed by photos and the census. “She said, ‘No, no she was at least 23.’ No, she was 18.”

Although these old, worn photographs serve as time machines of sorts, giving us insight into worlds past, they also reveal a stark comparison to how we value photos today.

“Old photos are really appealing because they have physical damage to them or sepia tone, which is really lovely,” Saylor said. “It’s fascinating to look at the outfits people were wearing and the ways they posed; I think about the cultural context and the social mores that led to that happening and what people were trying to say with these images. I think about how precious they were and how rare they are. In our modern lives, we can snap all the photos that we want and delete them, and they don’t have the same value as those that were made one by one.”

When sitting amongst photographs that were once made one-by-one, Saylor pores over the intricate details and suddenly she is in another world, imagining people’s voices, feeling the fabric of their clothes, and hearing the noises of the street where they lived.

“What I think initially is this is a really cool job that I have,” she said. “I don’t get to do that enough. I don’t have people banging down my door to do this work. I think about how exciting it is that, hey, I have this resource to utilize and that it’ll be really cool to examine these and attach them to living people.”

But when it comes to researching those people who stare back from sheets of paper and presenting those findings, reality can sometimes be a hard pill to swallow. Telling a client that their family has a history of mental illness, that there had been betrayal in the family or that their ancestors led difficult lives is never a simple task for Saylor, but that’s part of the job, and it’s part of their story.

“I research genealogy because it helps me and my clients understand their personal connection to America, and world history,” Saylor said. “When you know that your ancestor fought in the American Revolution, owned slaves, or was present in the major industrial sites of the country, it teaches you how connected we all are.”

Saylor found out that the founder of a prominent local restaurant once owned her house. Saylor moved to Buffalo six years ago and purchased a house on Prospect Avenue. She decided to do a practice property history on the place. The build date was 1869 and the house was a single family home until it was transformed into shared housing between 1905 and 1910.

“That’s where Frank Oliver’s family comes in,” Saylor said. (Frank Oliver founded Oliver’s restaurant on Delaware Avenue.) “I found out they were renters between 1912 and 1919 or so. I found it out because I was just randomly researching the names of people who had lived in my house.”

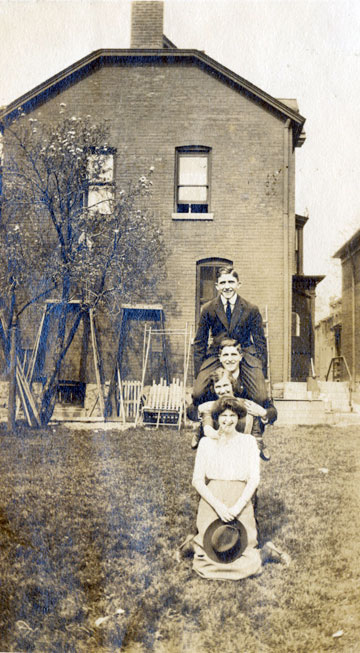

Her random research connected her with someone on Ancestry.com who had built an Oliver family tree. Ever curious about the people who used to occupy her residence, Saylor asked if they would send photos, which they did. The photos show a young family in 1914 playing around in the backyard, including one of them climbing on another’s shoulders.

“It was intense to see that—when you look around your home, and you now know what the faces of people who walked around that space 100 years ago look like. I look around the rooms in the house and I wonder ‘where did they sleep and what did they wear when they were inside this room I am sitting in now?’ What was their daily life like working at their jobs, and at night what books did they read in these rooms, and what did they think about?” She shared Frank Oliver’s story with Henry Gorino, a recent owner of Oliver’s, and he commissioned her to research a complete history of Frank and the restaurant

The past can give us just as many questions as answers, but we’re not really searching for answers. We’re searching for connections.

“We are hungry for connections and meaning, and authenticity,” Saylor said. “There’s a lot of artifice and inauthentic buildings, places and things that are only shadows of what they could be or used to be. Main streets are dying. That local social experience we used to have is being eradicated and makes us all want it more. People come to me to do a family history. They want that connection with the past, they want that authenticity of place people used to experience and want that genuine connection.”

Although Saylor often does work on behalf of clients, she has also done research for other genealogical or historical cases. She has been contacted by Meghan Smolenyak, who conducted research for the U.S. version of Who Do You Think You Are? a television series that explores the ancestry of celebrities. Smolenyak hired Saylor to conduct research in Buffalo on people who had lived here during a specific period of time.

When Saylor isn’t conducting historical research, she’ll have her hands in one of her many ongoing projects. Co-founder of Emerging Leaders of the Arts Buffalo (ELAB), she also runs City of Night, is involved with Buffalo’s Young Preservationists, writes “Preservation Ready” stories for Buffalo Spree Magazine, does architectural drawings for commission and in her down time completes crossword puzzles and watches old movies.

Saylor was born and raised in the rural town of Sterling, NY on Lake Ontario and obtained a bachelor’s of fine arts from SUNY Oswego. Although her degree says she’s an artist, Saylor always excelled in history and took loads of art history courses. Saylor made the move to Buffalo with her cousin, who was living in Williamsville at the time, with the shared goal of becoming entrepreneurs and artists.

“I moved to Buffalo, became vegetarian and sold my car,” she said.

The architecture and population of activists in the city inspired Saylor to the point where she said she will never move outside of The Queen City. And though she’ll never stop moving forward in all of her efforts, she continues to look back.

“I feel as though there is a mystery about the people who are dead,” she said, “and uncovering those mysteries helps me understand myself.”

Check out Dana Saylor's website at www.oldtimeroots.com

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n49 (Week of Thursday, December 4) > Photographic Memories This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue