Next story: Theater Community Focuses on Babel Author Suzan-Lori Parks

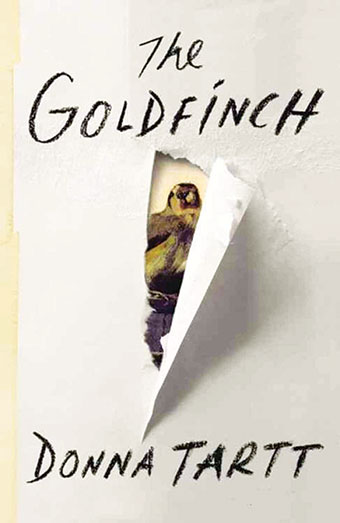

Book Review: The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt

by Woody Brown

To Have Loved a Beautiful Thing

The Goldfinch

by Donna Tartt

Little, Brown and Company, 2013

Art is always a generous endeavor. It creates for us the stuff of our dreams, the things we wished we could dream, the divinity of the unuttered words on the tips of our tongues. There is a primal comfort in encountering a work of art that is born of love. Some art, often the best art, comes from the hands of one whose sole guiding principle, when you really get down to the miraculously gilded tacks that hold the whole enterprise together, is an unbounded, irrepressible love: for mankind, for the world, for the word. This is philanthropy in its truest sense.

How can we love in the midst of this cesspool? What good is beauty if it lives mired in the murky mire of human suffering and the bitter joke of our short lives? These are the questions that preoccupy The Goldfinch, the third novel from Donna Tartt—or rather, their irresolvability creates her novel. It is a marvelous, epic tale, one whose 773 beautiful pages say, in short: “How can we? And yet, we do.”

Theo Decker, 13 years old, the narrator and post-9/11 Oliver Twist if ever there was one, survives the bombing of an art museum in New York City but his mother, Audrey, does not. Her incomprehensible absence, the possibility of which colored Theo’s existence well before it actually occurred, haunts the life Theo proceeds to build for himself against all odds, no matter how stacked those odds may be. So, too, do Pippa and Welty, a girl Theo’s age and her elderly uncle, who were also in the museum at the time of the bombing. Immediately after the explosion, Theo discovers Welty mangled and dying. He gives Theo a ring, tells him to ring the doorbell at an address in Greenwich Village, and indicates the place on the wall where The Goldfinch, a deceptively diminutive painting by Carel Fabritius, had hung. As Welty dies, Theo grabs the painting and runs from the rubble out into the world.

The address in Greenwich Village turns out to be the antique shop Welty and Pippa occupied with James Hobart (“Hobie”) until their lives were blown apart. Theo immediately gravitates to Hobie’s kind, sage demeanor and the world of aged wood, mellow patina, and gilded time that he inhabits. Pippa is there, too, but while Theo escaped the bombing physically unscathed, her body has been broken, riddled with the physical signatures of the brutal trauma Theo experiences behind his closed eyes. Meanwhile, his father, Larry, an alcoholic and a gambler who abandoned the family a year before the action of the novel begins, soon wrenches Theo out of the comfortable home of the Barbours, the wealthy family of Andy, the high school friend (“with his eerie flat voice”), with whom Theo had been staying. He is forced to move to Las Vegas with his father and Xandra, Larry’s gum-cracking, coke-snorting Wheat Thin of a girlfriend, but he takes with him the painting, the memory of his mother, and his love for Pippa.

If that sounds like a sizeable load for a prepubescent survivor of a terrorist attack to bear, that’s because it is. So sizeable, indeed, that Theo and Boris, the son of a Russian businessman whose vague career has something to do with mining, spend the next delirious year and a half narcotizing with everything from alcohol to LSD the wounds caused by the chains around their young necks. Theo’s albatross is a massive one, a nagging responsibility that is at once specific to his life and large enough to stand for the weight of the human condition on all our shoulders.

Major plot points—in fact, every change in the story that matters—are dictated by apparently random chance. But this ostensible arbitrariness cannot be reconciled with the truth; namely, that Theo’s life has a poetic trajectory, that he is often saved in one way or another, that a chance convenient meeting on the street can (and does, several times) forever alter his existence. In other fiction, especially the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky (which comes up several times throughout The Goldfinch), the improbable importance of chance events is often derided as melodramatic. It seems to violate the implicit pact of plausibility that we expect all writers to sign—this is the same agreement that dictates that, though Harry Potter can cast magical spells, he will not trip on a horcrux lying magically in the middle of the sidewalk on his way to learn how to make a phantom stag leap out of his forehead. Because, I mean, what are the chances? Nevermind the fact that real people can’t use magic. If we’re going to pretend that they can, they sure as hell had better be using it in a believable way.

Assuming so-called real world conditions, etc., many of the things that happen to Theo seem like weird, unbelievable coincidences at best, and stupid instances of deus ex machina at worst. But instead of condemning this as a problem, which it is not, we should recognize Tartt’s use of chance for what it is: a movement away from the tyranny of plausibility in favor of a deeper, more meaningful logic. The events of The Goldfinch are dictated by its characters’ desire, not by an uncaring, apathetic world. When Theo runs into Boris in a bar well into the novel, in a scene that is basically identical to an early chapter of The Brothers Karamazov, the reader understands that, though it is bordering on unbelievable, the meeting is necessary. It simply could not have happened any other way. As Dmitry says to his brother Alyosha, “Why was I longing for you, thirsting for you now, all these days and now? (It’s five days since I dropped anchor here.) Why all these days? Because I’ll tell everything to you alone, because it’s necessary, because you’re necessary.”

Necessary for what? Why does Theo seem to escape mishap after Dickensian mishap? Why is he so lucky, even when he is deeply unlucky? Because, as Theo says on the final page, “Fate is cruel but maybe not random.” Or rather, though it may seem random at the time, in retrospect, as we recall and relive the trials that precipitated our miraculously continued existence, nothing is random at all. We attribute a certain sense, an unknowable one, to everything from a planned attack to the proverbial gust from the wings of a butterfly. Tartt’s genius lies in her recognition of the several layers of this observation: that her characters did this in their lives, that we do this in ours, and that the process of creating The Goldfinch is a metaphor for this definitely human act, the act of writing a story.

All of this is as significant as the flame from a matchstick compared the gale-force winds of Tartt’s expertly told tale. She is a masterful writer. Her prose is infallibly appropriate, deftly constructed, and beautifully written. She has an eye and an ear for the small comforts (“a wilderness of gilt, gleaming in the slant from the dust-furred windows”) and tragedies (the inability to say the right thing, the refusal to want what you’ve been given) that define our daily lives. When Theo attains a brief respite from the storm of his life, it is hard as a reader to keep from sighing with relief. When he is stranded alone on the barren, rocky sea of the blighted edge of Las Vegas, the reader will find himself forced to read until the misery is resolved. I could not put this book down, not even if my life had depended on it. This novel is an extraordinary achievement, one completely bereft of any vanity on the part of the author or anything apart from the demands that truly great fiction makes on its vessel.

The titular painting by Fabritius figures prominently in The Goldfinch, and not just as a device: its light, the brushstrokes that combine to form its impossible beauty, the life of the bird itself, forever chained to its perch. But what Tartt never mentions is the small hinge visible on the piece of wood to which the perch is attached. It is a box, clearly, something we can open, but something Fabritius painted closed, its contents forever unknown. This novel is everything that small wooden box contains: possibility, beauty, the paradox of simultaneous liberty and enslavement. Most of all, it contains love. As Theo writes, “And I add my own love to the history of people who have loved beautiful things.” So do all of us, everyone, every life, every day.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n8 (Week of Thursday, February 20) > Lit City > Book Review: The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue