Next story: Chris Coste Returns to Buffalo

Before I Was So Rudely Interrupted

by Anthony Chase

New work by Lawrence Brose

On January 29, 1577, nearly five years after his abduction by the Spanish Inquisition on a charge of heresy, Fray Luis Ponce de León returned to his classroom at the University of Salamanca, and began his lecture with the immortal words, “Dicebamus hesterna die,” “As we were saying yesterday.”

“Indicted,” an exhibit of new work by artist Lawrence Brose has been extended through this Saturday at BT&C Gallery at 1250 Niagara Street. The work can be seen on Friday, July 24th from noon until 5pm, and on Saturday, July 25th from noon until 3pm.

This is the first major exhibit of Brose’s work since he was indicted on a charge of child pornography seven years ago. Brose fought that accusation vigorously. The case dragged on for years, preventing the artist from working while depleting his finances and nearly his spirit. Eventually, to make the legal nightmare go away, Brose agreed to plead guilty to a lesser charge of obscenity, and was sentenced to two years of probation.

While the plea stopped the legal machinery, the maneuver deprived Brose of any moment of total exoneration. Even now, media accounts of the case continue to stumble over themselves in their efforts to give equal time to a prosecution case that, at times, seemed tragically absurd, and ultimately proved to be untenable. Like the witches of Salem, who admitted guilt in order to avoid unjust punishment, Brose will evidently have to wait for time to vindicate him.

Lost in the legal shuffle, of course, is the artist’s actual work. This is where the fuss begins. Brose has always worked with images related to stigmatized sexual desires.

Ironically, hundreds of images that were included in the original indictment were taken from Brose’s 1997 film, De Profundis, and had been seen throughout the world, including at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. The 67-minute film takes its title from the famed letter written by Oscar Wilde to his former lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, during his imprisonment for gross indecency. Unlike Brose, Wilde insisted on trying for total exoneration in court. He lost and was destroyed.

Brose guides visitors through the current exhibit with a tone that fluctuates between ardor and sardonic humor. Indicating three photogravure prints with imagery sourced from an unfinished film that he was temporarily forced to abandon as a result of the proceedings against him, he wryly quips, “I call these, ‘Before I was so Rudely interrupted.’”

I think to myself, “As we were saying yesterday.”

And so the career of Lawrence Brose resumes.

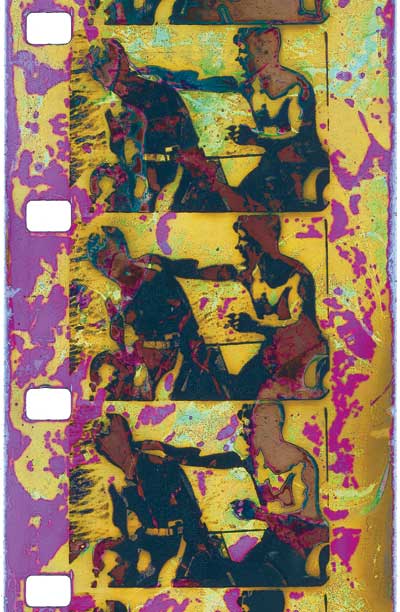

The photogravure prints depict images of Line-crossing ceremonies in which navies of many countries commemorated a sailor’s first crossing of the equator. These rites were often sexually charged and abusive, and were ultimately declared to be hazing. They are now more closely regulated. The prints provide an example of Brose’s fascination and virtuosity with printing techniques, and his preoccupation with manipulating images through various distortions. They also highlight his interest in repressed homoeroticism. Given the sexual content of the work, the implicit pun in “crossing the line” is a happy coincidence. As in many of Brose’s heavily reworked photographic images, the subject matter is not immediately discernable, serving as a kind of visual metaphor for stigma and repression—or for loves that dare not speak their name.

These photogravure prints are displayed adjacent to three images from Brose’s “De Profundis Series, 2015,” archival pigmented ink on Espon Somerset Velvet paper. The colorful images, each involving enlarged and reworked frames from vintage 16 mm black and white films, provide vivid insight into the project of Lawrence Brose’s work. At first, we seem to be looking at colorful abstract patterns, repeated vertically, three times. Scrutiny gradually reveals that the first print depicts a homosexual act from an early pornographic film; the second is a shirtless man on a dock by the water; and the third is of one man applying suntan oil to the shoulders of another.

Each of these film images contains a story of repression.

The early porno film would have been a kind of home movie shown in secret to a private party of friends. The man on the dock was extracted from a home movie, found by Brose at a yard sale, and depicts a man who, when the lens was pointed in his direction, immediately began to tease the camera with a kind of comical strip tease. The third image depicts a seemingly innocent and innocuous act that is, however, potentially sexually charged—one man applying suntan oil to the body of another man.

In each instance, we are encountering a kind of visual coding and a sexual secret. The first image is secret by virtue of being underground contraband. The second is stripped of its obvious sexual content by being presented as a joke. In the third, the homoeroticism is sublimated through a mundane activity. Brose further sublimates the sexuality of the images by distorting these images, creating the illusion that we are looking at purely abstract patterns of color, rather than frames from a film of a real life activity. In some of his images, the abstraction is nearly undecipherable.

In a series called In Carcere et Vinculis (Oscar Wilde’s own title for the letter his publisher would call De Profundis), Brose further explores the idea of stigmatized sexualities with homoerotic images of men reflected in Mylar. He uses the word “liquid” to describe these images, and they are, indeed “liquid” in many senses: flowing, elusive, and free. A photograph, or film, is the shadow of a material reality; Brose has pushed us several steps further away from the material world. He does not photograph his models. He photographs their reflections. These reflections are distorted by the ripple of the Mylar, and then further distorted when Brose manipulates the color.

While Brose’s legal troubles do not seem to have altered his artistic impulse or to have blunted its force, he says that the experience has altered his own thoughts about his work. It is possible that knowledge of his legal history may alter the public’s understanding of his work as well, but happily, this show does a great deal to deepen rather than to distort that understanding.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v14n29 (Week of Thursday, July 23) > Before I Was So Rudely Interrupted This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue