Next story: My Life as a Puppy: Casanova

Unhappy Trails: Brokeback Mountain

by George Sax

A new biography of Zane Grey, whose prolific output of Western novels made him the best-selling American writer in the first forty years of the last century, quotes a line from one of his books: “All the cowboys had secrets.”

Brokeback Mountain, Ang Lee’s new, widely remarked-on and much-heralded new film, is about two cowboys who share a secret, though presumably not the kind Grey had in mind. The chronological and qualitative gaps between Grey’s work, now largely forgotten, and Lee’s film, broadly described as “the gay cowboy movie,” may seem vast, but there are thematic and historical links.

The emphasis of much of the expectant commentary is on the movie’s homoerotic element, but it’s hard to believe the same breadth and intensity of interest would have developed if Brokeback Mountain didn’t involve cowboys, and didn’t entail, however obscurely, the old mythos of the American West. Its luster isn’t what it was when writers like Grey and Owen Wister were helping to embroider and commercialize it, and Hollywood was working its shopworn magic, but it still retains some potency. It’s been ingrained in the American ideology of proud individualism, and it operates its oppressive, semi-delusional effects on the movie’s two young men. (The cowboy mystique, somewhat vulgarly glamorized, has also exerted an attraction for gay men, as two unusually well-educated and perceptive members of that population reminded me the other day.)

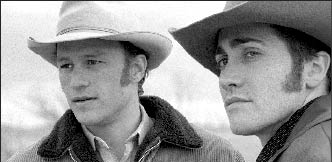

Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) are the two very young ranch hands who begin an unexpected, passionate and inexpedient relationship early in the movie. It’s a liaison that soon enough becomes disturbing and frustrating, and, ultimately, is deeply tragic.

Just as in the Annie Proulx short story the movie is based on, the boys meet when they’re hired to herd sheep on the titular Wyoming mountain over the summer of 1963. Both nineteen, on their own in Wyoming and barely scraping by, they initially bond over their joint isolation and hardship, and their common youth; before long, their shared loneliness, longing and need pull them together personally and sexually. But in August, as their employment ends and the dreary conventions of their lives reassert their sway, they laconically part.

When Jack reconnects with Ennis, four years have passed and both of them have married and become parents. Although the more adventurous, less guilt-ridden Jack argues for hightailing it away from their individual responsibilities toward a life together on a little ranch somewhere, Ennis can’t envision such a future. So, over the next decade and a half, they meet once or twice a year for “fishing trips.” In between, each suffers their years of separation in secret distress and almost unrequited yearning. “If you can’t fix it, you got to stand it,” Ennis advises during their first hungry reunion.

This central narrative structuring makes possible much of the film’s affecting impact and also its somewhat arbitrary quality. Their secretive romance in mutual absentia amounts to an artistic device or conceit that is quietly at odds with the movie’s carefully rendered, windswept natural settings as well as the dismal kitchen-sink realism of hardscrabble cow town life.

To be sure, some of this contrasting is deliberate. Lee and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto have meticulously composed a series of grandly-scaled outdoor scenes for the men’s activities together and apart. Rarely, if ever, has an American film made nature such a compelling presence since the salad days of director John Ford. This serves to tie the two men to their geography and society (although the filmmakers do seem to have missed an opportunity to visually translate a sentence in Proulx’s story that describes Jack and Ennis spying signs of each other’s proximity across a great expanse of Brokeback’s face, first in daylight, then after nightfall.)

The story’s almost abstract patterning of the men’s relationship isn’t without power, but you may be conscious, during the movie or afterward, of a schematicism. The beginning of their liaison may seem more persuasive than its playing out.

Novelist and screenwriter Larry McMurtry (The Last Picture Show, Lonesome Dove) bought the rights to the story shortly after it was published by the New Yorker in 1997. He had to wait another seven years before he could get a project moving forward with a screenplay written by him and producer Diana Ossana.

Adapting a novel frequently requires difficult decisions about compression, winnowing and rewriting. The movie follows Proulx’s story closely, but she breezes over the nearly twenty years of the men’s experiences, stopping only briefly at crucial turning points, referring to others after they’ve passed, and interjecting authorial insights and comments at various junctures. Her writing works to convey personal desolation and a subdued but insistent “lesson.” The screenwriters had to create most of the middle eighty or so minutes of the movie from what amount to several references and sketchy descriptions. The original story reflects Ennis’ experience and point-of-view much more than Jack’s, and the movie does a fair job of amplifying Jack’s life and character, but sometimes it seems to be marking time until it can return to Proulx’s original material. And in at least a couple of scenes, it edges toward, or into, soap opera.

Gyllenhaal makes the most of his uneven opportunities, more than many young actors could have. In one scene where the boss of the sheep outfit (an effective Randy Quaid) contemptuously makes clear his awareness of what the two boys were doing with each other on Brokeback, Gyllenhaal’s cowed, stricken, boyish visage is poignantly expressive.

But Ledger’s Ennis, almost of necessity, occupies the center of the movie, and it’s one of the most surprisingly accomplished performances in a long time. The actor makes Ennis’ wounded, confused pride and sometimes almost apologetic reticence bespeak a crude, stubborn nobility. Much of the movie’s impact depends on Ledger’s apparent conviction and understated interpretive skill.

Brokeback Mountain develops the quality of a mournful fable. It finally transcends its own awkward passages and didactic limitations.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n1: How Stupid is Your Daily Paper? (1/5/06) > Film Reviews > Unhappy Trails: Brokeback Mountain This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue