Scarlett Yes; Pimpernel No: V for Vendetta

by George Sax

The press booklet for V for Vendetta doesn’t contain a biographical note about Alan Moore, the writer of the comic and the graphic novel the movie is based on. He’s mentioned in the publicists’ text, but only his artist-collaborator, David Lloyd, got into the bio section.

This omission doubtless is due to the notably fractious Moore’s repudiation of the movie’s script as “rubbish,” and his unmet demand not to be mentioned at all. It’s also kind of ironic since the script, by the Wachowski brothers—Andy and Larry, who are also among the producers—has the awesomely mysterious, heroically insurgent title character say, “Words will always retain their power.”

But V is adapted from a work that relies on the graphic image, often garishly fantastic, a kind of work in which this alleged power of language is yoked to pictures, and is often the secondary element. Movies are, to be sure, a visual medium too, so it might be expected that comics could easily be adapted to cinematic purposes, but the recent record of this kind of effort doesn’t really bear out that assumption. The darker, more serious results of such conversions have included a number of failures, including Sam Mendes’ Road to Perdition, and last year’s Constantine with Keanu Reeves.

V is no such failure; it’s a dexterously made, consistently involving, persistently smart work of dynamic popular art. Its matchup of ideas, words and pictures is one of its underlying assets. Moore complains that the movie screws up his vision. I don’t know anything about that, but V works on its own terms.

The movie’s V is the sardonically masked avenger who wages a terroristic campaign against the brutal totalitarian regime that has taken over state power in Great Britain sometime in the near future. (The U.S. is disintegrating in civil strife.) Soon after the movie begins, V explosively demolishes London’s Old Bailey Court building to the accompaniment of Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture,” sent out over the dictatorship’s city-wide public address system. (John Hurt’s “Chancellor,” the supreme leader who only communicates over tele-hookups, even to his ministers, responds, “Add that to the blacklist; I don’t want to hear that music again!”)

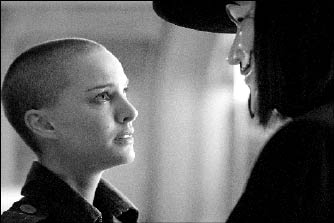

At about the same time, V encounters Evey (Natalie Portman), a young girl-Friday at BTN, the regime’s television network, and saves her from three police thugs. When she impulsively returns the favor later, he’s forced to carry her away to his manorial hideout, to keep her safe until he can pull off his grand scheme: to blow up the Houses of Parliament on November 5, Guy Fawkes Day. (The movie seems to get the historical significance of the holiday wrong.)

V is a typically fantastic comic-book character: garbed in black, face covered by a menacingly smiling ceramic mask, unarmed save for a set of knives, and executing what one villain dismisses as “karate tricks,” he acrobatically and lethally dispatches whole squads of police and soldiers. He’s also a techie wizard, able to commandeer the government’s audio and visual facilities. Not to mention his mastery of explosives engineering.

This central conceit places V smack in the middle of fantastical male-adolescent fare, of course, but it is surprisingly successful at enlisting the interest of a much wider audience. This may signal the enduring influence of adolescence, but the filmmakers have done their work with impressive facility, anyway. V moves fluidly, even gracefully, from scene to scene, imparting them with enough wit and dramatic impact to render the move consistently entertaining. It largely succeeds in creating a convincing fantasy world, where the characters aren’t so immediately preposterous that they perforate the illusion.

This is aided by the performances of a virtual album of important British character actors. These range from Sinead Cusack as a guilt-dogged government scientist with a terrible past, to Tim Piggott-Smith (years ago, a complexly immoral figure in the BBC’s miniseries “Jewel of the Crown”) playing a ruthless, quietly menacing security minister.

Stephen Rea is modestly but incisively effective as the senior police inspector on V and Evey’s trail. The movie takes on a noirish, policier flavor as he goes about his investigation amid growing, barely repressed moral qualms.

Portman had to provide the most varied, intense performance as the hunted, battered, decreasingly innocent Evey, and she has discharged her responsibilities admirably. As V, Hugo Weaving has to deliver his lines (most of them also post-dubbed) from within a top-to-bottom costume encasement and he comes across as lightly, amusedly mellifluous, for the most part, which is probably about as much as one could expect.

The Wachowski brothers’ three Matrix pictures were too often grandiosely incoherent, but V (directed by James McTeigue, first assistant director on The Matrix trilogy) is relatively easy to follow, even as it moves rapidly from sequence to sequence. There are some lapses: the movie doesn’t really explain the significance and origin of the nearly extinct red roses V leaves at the scenes of his crimes, and it’s not clear why Evey is out violating curfew in the movie’s early minutes.

There are some other things you don’t want to think about very much too, but in all its diverting cleverness, V has a more fundamental shortcoming: It represents an attempt at a moral and political statement imposed on a fantasy comic-book platform. The consequent product is a little unbalanced if you focus on this too intently. V is pop agit-prop, and it works quite well enough on that level.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n11: Street Smarts (3/16/06) > Film Reviews > Scarlett Yes; Pimpernel No: V for Vendetta This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue