Birds of a Feather, Briefly: Duck Season

by George Sax

Fernando Eimbcke came to his debut as a feature-film director from a career making music videos and commercials, but you’d never know it from his first film, Duck Season (Temporada De Patos). It’s an unhurried, soft-impact, subtly suggestive work that stands in contrast to countless other such debuts and to most of the other films on the market in recent years, for that matter.

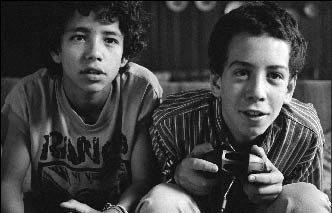

As it begins, in Mexico City, at the door of an apartment in one of those high-rise, reinforced concrete monuments to modernist architecture’s felonious past, a mother is bidding goodbye to her 14-year-old son Flama (Daniel Miranda) and his pal Moko (Diego Cantano) late on a Sunday morning. Before she can get away, they extort money for pizza and Cokes from her in return for promises of good conduct.

Once they’re alone, they joyfully contemplate a day of uninterrupted, unsupervised video-game playing and gluttony. But their day will not go as they so happily anticipated. It will be a Sunday of annoying interruptions, unusual diversions, sobering memories and revelations and challenging prospects. And some dope-fueled reveries too.

Eimbcke has infused Duck Season with a tone of sympathetic, but somewhat distanced, amusement. He has largely succeeded in maintaining its delicately calibrated pace and feeling. (Duck Season, which he also wrote, won 11 Ariels, the Mexican equivalent of Oscars, including for script and direction.)

Soon after it begins, the boys’ insulated recreation is violated by the intrusion of Rita (Danny Perea, also an Ariel winner), a 16-year-old neighbor of Flama who wants to use his mother’s oven to bake a cake. After he reluctantly agrees, their video game contest is interrupted by a power failure. Their unruffled reaction suggests this is a common occurrence in Mexico City.

Shifting their attention to the other major attraction of the afternoon, they phone for their pizza from a place with a 30-minute-delivery-time guarantee. When Flama’s watch doesn’t agree with the delivery guy’s—who has to climb eight flights in the absence of a working elevator—a standoff ensues: He won’t leave without payment, and Flama wants a free pizza. Meanwhile, Rita is busy in the kitchen with her own cake-timing problems, having enlisted Moko’s questionable help. As these two engage in a tentative, semi-romantic exploration, Flama and Ulises, the pizza guy (Enrique Arreola), are establishing a truce after a briefly contentious interlude.

Eimbcke has said he was surprised to find support for his “black and white film in which nothing happens.” (Alfonso Cuaron, the celebrated director of Y Tu Màma Combien, is distributing it in the US in conjunction with Warner Independent Pictures.) And little of conventional moment does happen. But during this Sunday afternoon in the apartment, these four establish real, if temporary, connections with each other, and perhaps new ideas about themselves. Eimbcke gently plays with their tentative interactions to create what is primarily a subdued but engaging cinematic chamber piece. There are developments in Duck Season, but they’re within the mood shifts and the rather oblique insights.

A little like Cuaron’s Y Tu Màma, this movie is about associations of limited duration and longer relationships, and about the hard-to-define impacts and changes both can have on individuals. It’s also about youthful spirit and youth’s disappointments.

By the picture’s end, Flama and Moko are facing a crucial change in their relationship. Eimbcke doesn’t lay much emphasis on this and neither do the kids. They mark this realization with studied, boyish nonchalance, but the unremarked feelings are recognizably present. All of the members of this temporary quartet are going to be reflecting on uncertain, unsatisfactory circumstances, but the movie only insinuates this prospect.

Comparisons are all too often glib exercises, but it may be minimally acceptable to call Duck Season a little like a combination of work by Jean Renoir and Jim Jarmusch, with a little stoner magic realism added in. It’s also very much an individual creation, of course. Eimbcke has worked it out with a blend of deliberateness and delicacy and infused it with a wistful humor. It has an unusually modulated resonance and an artfully delayed impact.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n15: Tom Golisano on the Buffalo Creek Casino (4/13/06) > Film Reviews > Birds of a Feather, Briefly: Duck Season This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue