Notes from the Underground

by Geoff Kelly & Louis Ricciuti

In 1944, in a memo to Captain Emery L. Van Horn of the US Army Corps of Engineers, the superintendent of the Linde Ceramics plant in Tonawanda described the different courses he might take to dispose of caustic liquid wastes contaminated by radiation. The first option, wrote A. R. Holmes, was to discharge the effluent into a storm sewer that empties into Two Mile Creek, which runs past a public park and into the Niagara River. Alternately, Holmes said, the effluent could be pumped into wells on Linde’s property, from which it would presumably disappear into the water table.

“Plan 1 is objectionable,” Holmes wrote, “because of probably future complications in the event of claims of contamination against us. Plan 2 is favored because our law department advises that it is considered impossible to determine the course of subterranean streams and, therefore, the responsibility for contamination could not be fixed.”

The Corps of Engineers agreed, apparently, and over the next two years Linde pumped nearly 50 million gallons of radioactive effluent into shallow wells on its property. Presumably it seeped into the aquifer, made its way to Two Mile Creek and the Niagara River and flowed over the Falls—unaccountable and and unaccounted for, carried by unseen waters.

It’s a story that illustrates the callous and cavalier disposal of toxic waste that continues to poison the region, and especially Niagara County. Here’s another, which begins several miles to the northeast in the City of Niagara Falls, and whose narrative also unfolds along underground waterways:

At the same time that Linde’s A. R. Holmes was fretting over future liability for radioactive contamination of the region’s water, Union Carbide’s Electro Metallurgical Company was the free world’s largest producer of uranium metal, used for the Manhattan Engineering District’s atomic bomb project and in atomic reactors. The plant, usually referred to as Electromet, was located at the corner of 47th Street and Royal Avenue, across the street from Harshaw Chemical, another Manhattan Project contractor. In all Union Carbide’s production and research facility occupied nearly 300 acres. Even today, aerial photography describes the site as a sprawling, rust-brown blight on the lanscape, fringed with green vegetation that has reasserted itself now that so many neighboring plants have shut down.

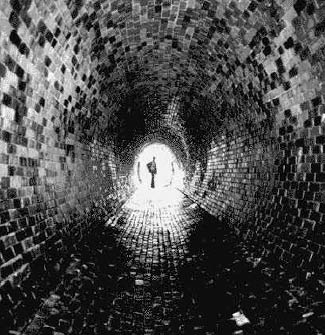

Running underneath Royal Avenue, between Harshaw and Electromet, is another invisible waterway: the Falls Street Tunnel, a municipal sewer that travels west all the way to the Niagara Gorge, intersecting numerous other tunnels along the way, including intake conduits for the New York State Power Authority that travel due north, passing adjacent to the Electromet site and underneath Hyde Park on their way to the New York State Power Authority reservoir in Lewiston.

It’s difficult to determine exactly how much toxic radioactive and chemical waste was generated at places like Harshaw and Electromet during the days of the Manhattan Project and the early days of the Atomic Energy Commission; it’s only good luck that turns up an incriminating letter such as the one from A. R. Holmes. Tens of thousands of tons of radioactive waste were dumped on the Lake Ontario Ordinance Works in Lewiston, according to documents that do exist, and much of that was certainly generated at sites like Electromet, Harshaw and neighboring facilities. Just in the seven years between 1965 and 1972, according to the Department of Energy, Union Carbide companies at the Royal Avenue and 47th Street sites generated 505 tons of radioactive waste, carrying 9,212 pounds of uranium oxide and 1,293 pounds of thorium oxide. All of that waste was buried—on site, nearby the Falls Street Tunnel and the intersecting NYSPA water intakes—in 55-gallon drums, piled in a ditch 20 feet deep and covered with four to five feet of soil.

There is no acknowledgment of that waste ever having been recovered; the drums in which it was buried certainly have outlived their usefulness. It’s easy to imagine—and, lacking evidence to the contrary, prudent to assume—that the contamination therein has found its way into the underground waterways and been carried afield.

There exists evidence, in fact, to suggest that this is the case. On February 7, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation held a public hearing at the Earl Brydges Memorial Library in Niagara Falls to discuss a proposed cleanup plan for the Frontier Chemical Royal Avenue Site. Frontier Chemical, the NYSDEC explained, operated a waste treatment, storage and disposal facility at 47th Street and Royal Avenue between 1974 and 1992, during which period several major spills of hazardous substance were documented.

Although more than 4,000 barrels of hazardous waste were removed from the site in 1993 and 1994, and the chemicals were drained from 45 storage tanks in 1994 and 1995, a subsequent NYSDEC study found that “significant groundwater contamination is migrating off-site into the Falls Street Tunnel, which is an unlined bedrock sewer tunnel located below Royal Avenue.”

The site history that NYSDEC presented in February begins with Frontier Chemical in 1974 and talks about hazardous chemical wastes. But of course there is more to the story; the industrial history of Niagara Falls does not begin in 1974. State officials at the meeting expressed surprise when they were told that Frontier Chemical sat where Harshaw Chemical, which handled radioactive materials, used to be. They seemed equally surprised to learn that Frontier sat across the street from the long-defunct Electromet, the government’s premier source for uranium metal in the early days of the atomic age.

If, as NYSDEC reports, Frontier’s chemical wastes contaminated the Falls Street Tunnel—and, perhaps, subsequently the NYSPA’s water intakes, the reservoir, the pumping station on the Niagara Gorge, the city’s wastewater treatment plant and everywhere else the water carried it—it seems reasonable, or at least prudent, to assume that the unaccounted for radioactive waste from Electromet found the same channels.

One last story, and for this one we travel north along the NYSPA’s intake conduits, toward the reservoir and another invisible waterway, Bloody Run Creek. Until 1992, Bloody Run was an open waterway, used as a sewer by adjacent industries, including Hooker Chemical and Titanium Alloys Manufacturing-National Lead of Ohio. It ran adjacent to the Hyde Park Landfill, made infamous by Hooker, which, over three decades, buried more dioxin-laden chemicals in the landfill than were sprayed in Southeast Asia during all of the Vietnam war.

Dioxin is what led to the burial of Bloody Run Creek. Dioxin, which entered the national vocabulary during the Love Canal crisis in the late 1970s, was the rationale for a remediation of Bloody Run performed in 1992.

Compounds from the landfill and the creek were detected approximately 1,600 feet away in contaminated groundwater seeping from the Niagara River gorge face. The remediation decreased, but did not eliminate, that seepage. And it buried the creek. Now Bloody Run surfaces only once, before disappearing into a culvert that runs beneath Niagara University.

Both the landfill and the creek were surely candidates for cleanups based on their contamination by dioxin and other potent toxic chemicals. But Titanium Alloys Manufacturing-National Lead of Ohio was an atomic contractor, too, just like Electromet, handling and disposing of radioactive materials. It currently operates as Ferro Electronic Materials, directly up gradient from Niagara University.

Between 1978 and 1979, the US Department of Energy commissioned EG&G Energy Measurements Group to conduct an aerial survey to document radiological contamination levels throughout Niagara County. (EG&G is a subsidiary of URS, the engineering firm that is acting as consultant to the NYSPA in its relicensing bid.) The resulting survey maps show a hotspot whose epicenter encompasses Bloody Run Creek. On the survey map, concentric contour lines represent elevated radiation exposure rates. In other words, Bloody Run is home to more than just dioxin.

The EG&G survey disappeared from the US Army Corps of Engineers headquarters website, where it had been hosted, just a couple months ago. It surely was available in 1992, during the cleanup of Bloody Run. That was characterized as a chemical cleanup; as in the case of the proposed Frontier Chemical remediation, perhaps radioactive waste ought to have been considered as well.

Ignoring such a significant and long-lasting part of the region’s atomic industrial history is fraught with consequences, not only for developers, current residents and future generations, but also for students at Niagara University, for example, and for those who continue to work on sites with a history of handling these exotic, hazardous materials. The 2000 Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act was intended to provide medical assistance and financial compensation to the workers and families of workers who became ill as a result of working in places like Electromet and TAM. But that act accomplishes nothing if the history of a site is not fully acknowledged.

This month two workers at Ferro died of cancers that most medical doctors relate directly to exposure to ionizing radiation. Both had been working at the company for more than 30 years and both died before they’d reached 55 years old. That doesn’t mean radiation caused their cancers, but it could have. Their families currently can’t appeal to the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program for this compensation because the program has not determined dose levels that previous workers at TAM-Ferro absorbed. Nor, therefore, can a dose be determined for current workers.

And how can it be, when the history of those sites is shunted underground?

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n21: The Great Wind Debate (5/25/06) > Notes from the Underground This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue