Next story: Letters to Artvoice

Crossing the Line

by Geoff Kelly

Last week, after the arrest of 17 suspected terrorists in Ontario, Indiana Congressman John Hostettler, chair of the House subcommittee on immigration and border security, claimed that Toronto is a breeding ground for Islamist terrorism.

“South Toronto, like those parts of London that are host to the radical imams who influenced the 9/11 terrorists and the shoe bomber, has people who adhere to a militant understanding of Islam,” the six-term Republican said. (South Toronto, he explained to Canadian reporters unfamiliar with the neighborhood, was “a location which I understand is the kind of enclave that allows for this radical type of discussion to go on.”)

Hostettler made his remarks, reported with barely veiled sarcasm in the Toronto Globe and Mail, during his subcommittee’s hearing on implementation of the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI), which would require anyone passing between the US and Canada to present either a passport or a proposed alternative to a passport beginning January 1, 2008.

“If we needed a clear case for why there needs to be a dramatic increase in security along the northern border,” said Hostettler, who was arrested two years ago in Louisville, Kentucky for carrying a loaded handgun into the airport, “the example of this past week’s terrorist arrests in Toronto is very dramatic.”

WHTI has its origins in Hostettler’s subcommittee in 2003, a reaction to Washington sniper John Allen, who forged US driver’s licenses for Caribbean residents. As with Canada, a driver’s license is all that a US citizen needs to pass back and forth between many Caribbean countries and the US. Currently the US, Canada, Bermuda and Mexico do not require passports of one another’s citizens.

WHTI was passed by the House in response to the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which implemented a number recommendations of the 9/11 Commission. The Senate has passed its own version of WHTI, calling for a delay in its implementation until June 1, 2009.

The otherwise minor differences between the House and Senate bills have not yet been reconciled. While Hostettler and his House colleagues from the heartland are resisting any modification to or delay in enacting the provisions of the House bill, the Senate and legislators from northern border states, from Washington to Maine, are trying to put on the brakes.

Congresswoman Louise Slaughter of New York State’s 28th District, which includes Niagara Falls and Buffalo’s northern suburbs, has asked for an economic impact study to determine if the cost to trade and tourism outweighs the benefits in terms of security. She has been joined in her criticism of WHTI by Congressman Brian Higgins, whose 26th District comprises Buffalo as well as points south and east. They come armed with a recent report by the General Accounting Office that indicates that the Department of Homeland Security is completely unprepared to implement the provisions of WHTI by the end of 2007.

Meanwhile, citizens on both sides of the border complain that personal liberty is about to suffer further degradation at the hands of a US federal government that scarcely believes in the existence of a right to privacy.

They also complain that WHTI will have a devastating economic effect on border communities in both countries.

The benefits of open borders

The North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect in 1994, permitting a free flow of goods, services and capital across the US-Canadian border. The US and Canada, already each other’s leading trade partners since the end of World War II, now share the largest and most productive bilateral trading relationship in the world.

By the numbers, as collected by business and trade organizations on both sides of the border, all of whom are leery of WHTI and hope it dies a quiet death:

—In 2005, bilateral trade between the US and Canada totaled more than $580 billion—that is, almost $1.6 billion in goods and service cross the border every day. About one sixth of that trade crosses the six international bridges in the Buffalo-Niagara region.

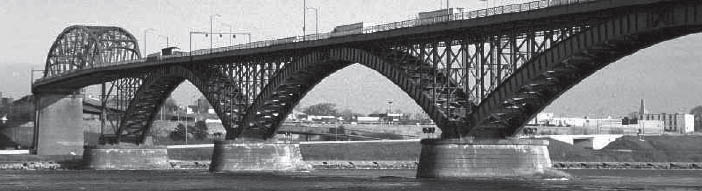

—Approximately nine thousand trucks cross the US-Ontario border each day. More than one million trucks a year use the Peace Bridge and the Lewiston/Queenston Bridge each year, an increase of nearly one third since NAFTA took effect.

—About 20,000 vehicles and $160 million in trade cross the Peace Bridge every day.

—Canada is New York State’s primary export market, with $30.2 billion in trade in 2004. More than two thirds of Western New York’s exports go to Ontario and other Canadian markets.

—Trade with Canada supports more than five million jobs in the US. Every vehicle in North America contains nearly $1,250 in Canadian-made parts.

WHTI does not target that free flow of trade directly, but it is likely to slow traffic. Regardless of how one feels about NAFTA, its impact on wages and benefits for US workers and its effect on the nation’s trade imbalances, it doesn’t behoove the US to lower economic trade barriers and then raise logistical ones. And it makes no sense, notwithstanding the paranoid fantasies of feckless ideologues like Hostettler, to treat the Canadian border as if it presented the same security issues as the Mexican border.

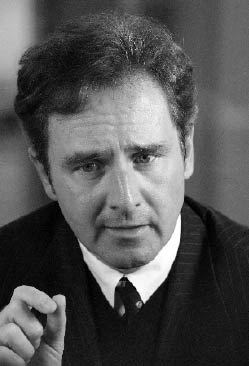

“I think there’s a more stable relationship between the United States and Canada than there may be between the southern border and Mexico,” Brian Higgins says. “We don’t have a lot of illegal immigrants coming in through the northern border. There are certainly some, but it’s a much different situation. And I’m simply saying that you can’t advance the North American Free Trade Agreement 10 years ago to remove the barriers to commerce and then put up new ones now. This is all being done in the name of border security, but looking just below the surface will reveal that this is nothing more than a cosmetic, generic answer to a problem that requires more expertise and more and better trained personnel.”

Tourism is bound to take a hit, too, and Western New Yorkers and Ontario natives will feel that acutely. Again, some numbers, the most conservative estimates Artvoice could find:

—US citizens made 31.6 million trips to Canada in 2005, including 15.7 million same-day auto trips, spending a total of $7.5 billion.

—Canadians made 37.8 million trips to the United States in 2005, including 22.3 million same-day auto trips, spending a total of $10 billion. Canadian visits to the US increased dramatically between 2004 and 2005, as the Canadian dollar gained value against US currency.

—New York State and Ontario residents account for more than half that traffic annually and perhaps a third of that financial impact.

—In all, Buffalo-Niagara cultural organizations record 50,000 Canadian visitors a year, with revenues exceeding $500,000. (And it works both ways—for example, 40 percent of the Shaw Festival’s subscribers come from the US.)

—There are more than 1,000 Canadian students studying at Buffalo-Niagara universities. D’Youville College’s student body is about 50 percent Canadian.

—Western New York hospitals admit more than 1,000 Canadian patients each year.

—More than 200,000 Canadian skiers visit resorts in the Southern Tier annually, with revenues exceeding $15 million.

—Amusement parks receive another 65,000 Canadian visitors and revenues exceeding $1.3 million.

—The region’s restaurants estimate that five percent of their annual business comes from Canada, generating at least $250,000 in revenue.

—Shopping centers like the Walden Galleria estimate that 38 percent of their customers are Canadians taking advantage of the strong Canadian dollar. They spend more than $15 million each year in Western New York.

Only 34 percent of adult Americans hold passports. Only 41 percent of adult Canadians hold passports. Cross-border traffic is bound to suffer if WHTI is implemented. One study estimates that WHTI’s passport requirement will result in a 12.3-percent decrease in cross-border visits in 2008. Just taking into account those economic sectors listed above, that could cost Western New York businesses more than $3.5 million.

“We’re already seeing a lessening of the tourists, which is a problem, because they think they already need a passport,” Louise Slaughter says.

That projected $3.5 million loss in 2008 does not take into account the Buffalo Sabres, the Buffalo Bills and the Buffalo Bisons. It does not account for airports. The Buffalo Niagara International Airport is popular among citizens of Southern Ontario because it’s easier and cheaper to use than Toronto’s Pearson International. Likewise, New Yorkers use Pearson International because it offers a greater choice of airlines and destinations. Consider losses to wine tours, golf course operators and outdoor festivals. Consider that fewer gamblers will make the trek across the bridges to the Seneca Niagara Casino and the proposed Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino, should it move forward.

Factor in losses in those and other economic sectors, tourism experts say, and that projected $3.5 million loss in revenue to Western New York businesses in 2008 could double or triple or more.

“I think the results would be devastating,” Slaughter says. “Like anything else in public policy, WHTI should include a fair cost-benefit analysis. And I’m saying that if, in fact, the federal government is willing to undertake that—which they’re not, obviously—it would reveal that the costs far outweigh the benefits. And there are other ways to enhance border security without undermining economic development and life quality.”

A new card for your wallet

Ostensibly to defray fears that requiring a passport to cross the US-Canadian border would seem too onerous to those living in northern states, the Department of Homeland Security proposed a cheaper, more quickly attainable alternative: a credit-card-sized ID with a thumbprint or other biometric scan of the bearer. The card would have an electronic signature that would correspond to a database, maintained by Homeland Security or, more likely, one of its private contractors, containing personal information about the bearer.

The border pass card would also be outfitted with a radio-frequency identification device, or RFID, which would allow the card to be scanned at a distance of up to 35 feet, using currently available technology.

A US passport costs about $100 and takes four to six weeks to process. Canadian tourism boosters say a family of four, faced with tacking $400 on to the price of a vacation, will go somewhere else. They’ll spend their leisure time in the US or figure, as long as they’re paying so much, that they might as well take the kids to Paris or London. US tourism experts say the same will happen in reverse here—Canadians will choose to spend their time and money elsewhere.

The Senate’s version of WHTI puts a cap of $34 on the alternative border pass card. Louise Slaughter has joined other northern state legislators in introducing legislation that would cap the price at $20. Her legislation also postpones implementation of WHTI until September 2009, instead of January 1, 2008, as favored by the House, or June 2009, as favored by the Senate; she reasons that such a profound change in how the border does business should not be implemented at the beginning of the summer tourist season.

Whatever the price, there is a class issue involved in charging for the privilege of identification. If a citizen has to pay for an ID card that endows the bearer with special privileges, such as a passport or a border pass card, then the economically underprivileged automatically become bigger targets for law enforcement. If you can’t produce the document that ostensibly proves you are not an illegal immigrant or a terrorist, you fall immediately under suspicion.

If you don’t believe that, ask a bouncer at a bar what he thinks when a patron, asked for proof of age, says he or she doesn’t have a driver’s license and produces, for example, a birth certificate or a college ID instead.

What kind of security?

Although there is no indication that the suspected terrorist cell that was busted in suburban Toronto on June 2 had any real intention to attack US targets, the group’s lethal nature and its proximity to the border are likely to stir concern that other groups so inclined could make the border crossing. But since all of those apprehended are residents of Canada, and most are Canadian citizens, most would have been eligible to obtain proper identification—whatever form that ID eventually takes. Indeed, the Mounties didn’t monitor and eventually arrest the 17 suspected terrorists because their IDs were out of order; they were caught because the Mounties were surveilling a mosque whose imam, the Mounties believed, was encouraging his constituents to pursue violent jihad. That surveillance led authorities to monitor the movements of a particularly suspicious group of men and, eventually, to set up a sting whereby they pretended to sell the suspected terrorists the makings of a fertilizer bomb.

That raises a separate issue regarding profiling and its effectiveness as a security measure—many security experts argue that profiling instructs determined criminals how not to act and how not to appear—as well as the issue of civil liberties. But it has nothing to do with identification.

Security experts agree, in fact, that checking ID is not as effective a safeguard as attentive security personnel reading people for signs of uneasiness or ill intent. As cybersecurity expert and author Bruce Schneier wrote not long ago in the San Francisco Chronicle,

…verifying that someone has a photo ID is a completely useless security measure. All the 9/11 terrorists had photo IDs. Some of the IDs were real. Some were fake. Some were real IDs with fake names, purchased from a crooked DMV official in Virginia for $1,000 each. Fake driver’s licenses for all fifty states, good enough to fool anyone who isn’t paying close attention, are available on the Internet…

Harder-to-forge IDs only help marginally, because the problem is not making sure the ID is valid. This is the second myth of ID checks: that identification combined with profiling can be an indicator of intention…[but] profiling has two very dangerous failure modes. The first one is obvious. The intent of profiling is to divide people into two categories: people who may be evildoers and need to be screened more carefully, and people who are less likely to be evildoers and can be screened less carefully. But any such system will create a third, and very dangerous, category: evildoers who don’t fit the profile.

…There’s another, even more dangerous, failure mode for these systems: honest people who fit the evildoer profile. Because evildoers are so rare, almost everyone who fits the profile will turn out to be a false alarm. This not only wastes investigative resources, but it causes grave harm to those innocents who fit the profile. Whether it’s something as simple as “driving while black” or “flying while Arab,” or something more complicated like taking scuba lessons or protesting the current administration, profiling harms society because it causes all of us to live in fear…not from the evildoers, but from the police.

Who knows how many investigations the Royal Canadian Mounted Police began before they got lucky—as we all did—and pegged this suspected terrorist cell? Schneier recommends dropping ID checks on domestic flights, for example, in favor of random screening of passengers. “Security is a trade-off; we have to weigh the security we get against the price we pay for it, “ he writes. “Better trade-offs are to spend money on intelligence and analysis, investigation, and making ourselves less of a pariah on the world stage…Identification and profiling don’t provide very good security, and they do so at an enormous cost.”

Higgins believes that a photo ID and a birth certificate—the same documents required to obtain a passport—ought to be sufficient documentation to pass across the US-Canadian border. “I think more border security, more immigration personnel would meet the objective of enhancing border security better than would a universal mandate for passports,” he says.

“These border security guards, these immigration officers are trained to detect certain behaviors, to detect certain distinctions, and perhaps those who should be detained for further screening. I just don’t think passports are going to do it in this day of information technology, which evolves very, very fast the ability to fraudulently replicate passports and create false passports.

“My concern is that it’s more cosmetic and less substance,” Higgins says. “I think this administration is taking a very generic and generalized approach to border security. And they’re not recognizing the unique characteristics between the two borders.”

Nor is Higgins impressed with the idea of some new form of ID, whether or not it is cheaper and more quickly obtained than a passport. “They’re all the same—they’re silly, they’re cosmetic, they’re passport lite. The bottom line is a birth certificate and a photo ID, as those are the forms of identification required to get a passport in the first instance.”

In any case, as Slaughter points out, the GAO report she and other northern state legislators asked for indicates that Homeland Security is completely unprepared to implement the WHTI regime on the Canadian border, even though the proposal has been floating around for at least three years—longer, if one considers the cries for a mandatory national ID card, that bete noire of civil libertarians everywhere, that gained volume after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

How unprepared is Homeland Security? It was only two months ago that Homeland Security officials briefed members of the Smart Card Alliance, a trade group of companies, regarding the kind of cards the new system would require, and about the associated databases of personal information about their bearers. Jim Williams, director of the US Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology program (US-VISIT), said the department wanted a card with thumbprints or iris scans and RFID technology that could be read at least 30 feet away, so that border guards can pull up information on the card-bearer as his or her car rolls up to a checkpoint.

The RFID technology has already been tested. Biometric scanning systems that can be installed at border crossings don’t exist yet. If they did, Williams said, “Shoot, we’d take that now. I would.”

But they don’t, so he can’t. Still, members of the Smart Card Alliance—predictably, considering they stand to make a lot of money—have joined Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff and Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice in saying that the technology will be ready and in place in time for the current January 1, 2008 deadline to implement WHTI. They all argue, along with the likes of Hostettler, that there can be no delay—that every day that passes without stricter border-crossing requirements between Canada and the US is a day of opportunity for terrorists.

“They never got it done, we still don’t have anything done and the report says that they’re nowhere near even deciding what they’re going to do,” Slaughter says. “And what we’ve asked for from the GAO was an economic impact study. They can’t do one, though, because there’s as yet nothing to study. So that gives me great comfort and hope that they are certainly not going to be ready by 2008, and once they come up with something we’ll get our impact study. In the meantime, we’ll try to change everybody’s mind. We’ve got to find some way that we can consider the northern border separately from the southern border.”

The road to a national ID card

In the end, the arrest of the 17 suspected terrorists might be offered as evidence that good policework provides better security than a new, more stringent identification requirment that hurts the economies of the northern states.

So why do it? It’s expensive, controversial and presumptuous—many Canadians, both in and out of government, are furious that the US wants to dictate the terms of border crossings unilaterally and possibly wire Canadian citizens into an ID system that might compromise their privacy.

It’s also not safe. In another essay, cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier writes about the folly of RFID systems—the tiny radio antennas that Homeland Security wants implanted in US passports, the border pass card and even in driver’s licenses. Because the RFID systems that Homeland Security is asking for allow ID cards to be read from a distance, information thieves with sophisticated scanners can read them, too—and potentially steal your identity, drain your bank account or alter information in your profile. Homeland Security insists that can’t be done, but professional demonstrations have proved that it can be. Why then, Schneier asks, would the US State Department want to use RFID in US passports—a measure that is forthcoming in October of this year, whether the US-Canadian border stays open or is closed by the onerous and ineffective provisions of WHTI. He asks why the Bush administration wants RFID implants in passports that can be read from 30 feet away, when it’s more expensive and renders the bearer’s information vulnerable to attack from the sort of people the measure is supposed to foil?

Here’s the answer given by Schneier, an industry professional with a reputation for clear, unbiased analysis:

The administration is deliberately choosing a less secure technology without justification. If there were a good reason to choose that technology, then it might make sense. But there isn’t. There’s a large cost in security and privacy, and no benefit…

Unfortunately, there is a reason. At least, it’s the only reason I can think of for the administration wanting RFID chips in passports: they want surreptitious access themselves. The want to be able to identify people in crowds. They want to pick out the Americans, and pick out the foreigners. They want to do the very thing that they insist, despite demonstrations to the contrary, can’t be done.

Normally I am very careful before I ascribe such sinister motives to a government agency. Incompetence is the norm, and malevolence is much rarer. But this seems a clear case of the government putting its own interests above the the security and privacy of its citizens, and then lying about it.

Investigative journalist Greg Palast, whose most recent book, Armed Madhouse, was released on June 6, has been tracking the use of voter databases for political purposes since the 2000 presidential election. In that election, and all subsequent US elections, Palast has found numerous cases in which private companies, such as the ones that will bid for the contract to implement a new border pass card or to maintain the associated databases for Homeland Security or the State Department, have helped state governments in efforts to disenfranchise voters, particularly African Americans. Tens of thousands of voters in Florida had their votes discounted in 2000 because a database purchased from a company called ChoicePoint erroneously identified them as convicted felons, who are barred from voting in Florida. ChoicePoint also provided erroneous lists of ex-felons to help Republicans mount voter challenges in Texas, even though it’s not illegal for ex-felons to vote in that state.

Similar incidents and voter challenges took place in 2004, in Florida, Ohio, New Mexico and other swing states, primarily undermining the African American and Native American vote. Palast says it’s going to happen again in 2008, and that Hispanic voters are the next targets.

Palast sees a continuum between the voting scandals he has uncovered in the last three elections and the still unfolding scandal around the Bush adminisitration’s acknowledgment that it has used the National Security Agency to spy on and collect information about US citizens. Any kind of information gathering, he says, no matter what its original intention—fighting terrorism, securing borders—leads eventually to misuse of that information.

“I think that you cannot disconnect the spying on Americans from the fix of the elections,” Palast recently told Artvoice. “And the signal of this is that they are the same companies. Choice Point, the company that abetted the vote scrub in Florida in 2000, is also the company and it is creating the databases for the war on terror.”

Republicans, he says, have been pushing for a national voter ID card, ostensibly to prevent irregularities of the sort Palast investigates. This too would be manufactured and the associated databases maintained by private contractors. “You say, ‘Well, what’s wrong with showing your ID?’ The answer is, what crime are we preventing? I’ve looked all over the country but found only one case out of 100 million voters where a person knowingly cast his vote in someone else’s name. I’m just looking for, say, about 10 out of 100 million or 100 out of 100 million—wouldn’t that be fair if we are going to change our entire voting system? Shouldn’t there be at least one in one million cases of this? But instead, we know 300,000, disproportionately minority and Democrats, were denied the right to vote because they did not have the right ID. It is as selective as literacy was during the Jim Crow era.”

Many US citizens shrug off invasions of privacy and the collection of personal information by government agencies, using an age-old argument: If I’ve done nothing wrong, if I’ve got the right ID, I’ve got nothing to fear. Bruce Schneier counters that argument with a quote from Cardinal Richelieu: “If one would give me six lines written by the hand of the most famous man, I would find something in them to have him hanged.”

That is, you never know how information will be used. Liberty, Schneier argues, requires both privacy and security—not some choice between the two.

“No one seems to be asking, ‘Why are they collecting this stuff?’” Palast says. “There is this fake battle being set up between civil liberties and the protection against terrorists. They’re saying that you have to give up a little bit of our freedom to be protected. No. They’re not protecting us. We are giving up our freedoms but receiving nothing in return. What are they using these documents for? Why are they building the lists? There are probably many reasons, but one thing I know for sure is how the lists are used. I know that they are used for manipulating elections.”

So how do proposals like WHTI—bad for business, ineffective as security, bad for privacy and possibly bad for democracy—wind up being voted into law? Congressman Brian Higgins has one answer:

“Civil rights take a beating in times of war, in particular this new post 9-11 era,” Higgins says. “But you’ve got to try to find that balance somewhere, and the problem with legislation in Washington is that so much gets bundled that you’re voting for a lot of things that you like in one bill, and in doing so you’ve got to embrace things that you don’t like. It’s very, very complicated.”

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n24: Crossing the Line (6/15/06) > Crossing the Line This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue