Even in Eden, Boys Will Be Boys

by Girish Shambu

In our DVD age, there are still movies that cry out to be seen on the big screen. This is especially true for epic-scale, large-budget films with lavish production values. Mongolian Ping Pong is a Chinese film that demands to be experienced in the theaters, but for none of those reasons. It’s a small, intimate, quiet film made on a modest budget—the kind of film that audiences often choose to watch at home on DVD.

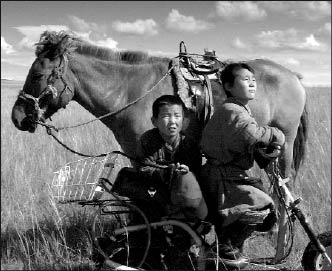

The reason why this is a big-screen movie has to do with its setting: the unspeakably picturesque, wind-swept grasslands of outer Mongolia. The movie tells the coming-of-age story of a boy who lives with his sheep-herding family in a tent home in the steppes. He finds a ping pong ball floating in a creek one day, and is fascinated by this unknown object. His grandmother theorizes it to be a “glowing pearl,” and the lamas at the monastery are stumped by it. The movie follows him and his friends as they try to unravel the mystery of the ball, learning a little bit about both the world and themselves in the process.

The unsentimental modesty of this tale packs a strange and wonderful punch because of the awe-inspiring Mongolian landscape. In this globalized age, when cultures and countries are transforming rapidly—and perhaps starting to lose what once made them unique and precious—this movie looks like a dispatch from another planet. We are surrounded by piercing blue sky, slow serpentine streams, and tall grasses swaying languidly in the breeze. When night falls, the land is silent and chilled by the silver light of the moon and stars. The shooting style of the movie perfectly complements the majesty of this landscape. The wide shots panoramically take in the horizon. The camera is stationary and calm; it is there to observe, not to draw attention to itself.

But this movie is no bland picture postcard. Hiding in its crevices are signs of change encroaching upon a way of life that has stayed nearly intact since these were the stomping grounds of Genghis Khan several hundred years ago. A traveling salesman with a battered jalopy comes to visit the family every few days and brings news and goods from the outside world. At first, the puzzled family pores over an issue of Elle magazine; then they negotiate to buy a new kitchen appliance in exchange for two sheep. (The salesman’s pitch: “It’s used to make a famous American tea called coffee.”) And inevitably, the family thinks about acquiring a TV set.

In our modern, fast-paced Western society, the discovery of a ping pong ball by a 10-year-old boy would barely merit a blink, but the Mongolian kids in the movie are utterly entranced by its mystery. It’s a marvelously revealing touch: The wonders of childhood are sometimes enhanced and sustained by scarcity. In our information-saturated lives, when anything we want or need is close at hand and instantly accessible, perhaps we make it a little harder for children to notice and be captivated by the small wonders of daily life.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n25: War Heads (6/22/06) > Film Reviews > Even in Eden, Boys Will Be Boys This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue