John Wayne Died for Your Sins

by George Sax

According to Edward Norton, the star and one of the producers of Down in the Valley, he and director David Jacobson watched old movie westerns together in preparation for beginning work on the film. It figures.

Valley isn’t really a western—either neo or quasi—but it alludes to, and appropriates ideas and images from, decades of horse operas. It’s unabashedly reliant on these ancient Hollywood genre products even as it pointedly comments on the storied American West of the frontier era. Or, more accurately, on the West as it’s been portrayed in innumerable, largely forgotten movies and in popular fiction, from James Fennimore Cooper on through Owen Wister, Zane Grey and Max Brand.

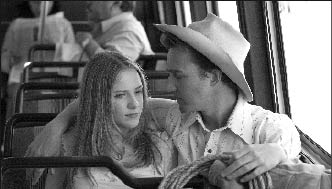

Harlan, the initially appealing and forlorn, eventually furtive and dangerous young man played by Norton, presents himself as an anachronistic exemplar of the precepts of strength, modesty and independence of the heroes of these stories. We’re introduced to him when Tobe (Evan Rachel Wood), a bored, restless teenager, meets him at the San Fernando Valley filling station where he works. She’s on her way to the beach and, intrigued by his odd, shy charm, impulsively invites him to come with her and her friends. An idyllic summer day ends with Tobe’s seduction of Harlan and the beginning of an unlikely and increasingly dubious affair.

Tobe lives with her timidly anxious younger brother, Lonnie (Rory Culkin), and her strong-minded but increasingly frustrated father, Wade (David Morse), an officer at a juvenile detention facility. Their household is a picture of suburban alienation, beset by festering resentments and intimations of suppressed violence. There is also love, but it too is largely suppressed. Into this barely contained volatility comes Harlan, and his misunderstanding of its dynamics sets in motion a spiral of disaster.

Jacobson rather obviously wants Harlan’s delusional persona to resonate with us as a distorting echo of the American frontier traditions—themselves tinny distortions. More importantly, he wants Harlan to personify the pervasive continuing influence of the trite conventions of popular culture’s use of Western history. Harlan has fashioned his own self-mythologizing identity largely out of these cliches, and from the intense American attraction to guns.

Wade is also a gun fancier and collector, but he denies Lonnie access to the weapons. When Harlan takes the kid shooting with his own ridiculously iconic Colt .45s, he’s finding an earlier incarnation of himself in Lonnie.

Jacobson seems to have hit on some interesting material in his concept of Harlan. The attempt to imply a linkage between his pathology and the rootless, sometimes violence-inducing tensions in America’s expansive post-urban societies holds some promise. There’s an at-once amusing and disconcerting visual discordance in shots of Harlan riding horseback through stretches of expressway-dominated landscape. Jacobson and cinematographer Enrique Chediak’s images of the Valley are richly and softly luminous; the area has probably never been represented so attractively and with such disquieting symbolism.

But the film never really comes to grips with Harlan and his environment. He never gels as a character. Jacobson’s own involvement with the pulp-created West seems to get in the way, sometimes. There are recurring allusions to the history of assembly-line movie depictions of the Old West.

Jacobson may have wanted to do too much and not been able to work it all out. Harlan may have been too novelistic a conception for a movie. Whatever happened (including Norton’s reported intervention in the script’s preparation), the character becomes less convincing as he evolves into someone more weird and threatening. Harlan’s biography is slipped in only perfunctorily and carelessly. And it may be a signal of the movie’s eventual incoherence that Harlan is more reminiscent of Robert DeNiro’s Travis Bickle than anyone from the repertoire of John Ford or John Wayne, or from one of the thousands of ground-out oaters from Hollywood’s mills.

By the time Jacobson shows people filming a scene that’s almost straight out of Ford’s My Darling Clementine, he and his ideas seem overwhelmed. Is his movie really about Harlan’s mystified obsessions, or about Jacobson’s own cinematic preoccupations?

Valley doesn’t realize its interesting ambitions.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n25: War Heads (6/22/06) > Film Reviews > John Wayne Died for Your Sins This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue