Close to Home

by Eric Jackson-Forsberg

Ever since the Renaissance, at least, artists have been turning to the mirror and using what they find there as a readily available and deceptively simple subject. And with the advent of modernism, artists’ self-portraits assumed a bewildering variety of forms, from Frida Kahlo’s autobiographical dream sequences to Marc Quinn’s bust made of his own frozen blood. But no artist of the 20th century has adopted self-portraiture as a modus operandi as much as Chuck Close. His nearly 40-year odyssey of systematic self-representation is brilliantly displayed in Chuck Close: Self-Portraits 1967-2005, now on view at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

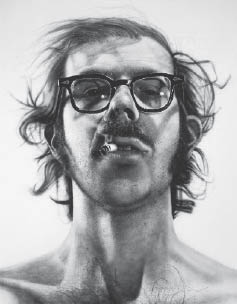

Although this exhibition is dedicated to the image of one man, we soon find that Close’s obsession is not with his own features or identity but with the process of image-making and making the familiar uncanny in its hyper-reality. The exhibition traces the development of Close’s signature technique of photorealism through obsessive-compulsive experiment. Eschewing the decadence of abstraction in the late 1960s, Close helped push the pendulum of the new as it swung to the extremes of realism. He didn’t stop there, but took the early success of Big Self Portrait (1967)—a nine-by-seven foot “head” of the intense, scruffy young artist—and continued to develop and painstakingly implement a painting system borrowed from mural painters: transferring an image (in this case from a photograph) to a larger format by means of a superimposed grid, breaking the whole into an array of cells that may be rendered individually to form the new image.

In this manner, Close created colossal, airbrush-precise portraits of friends and fellow artists and composers (including Richard Serra and Phillip Glass). But as bold as these billboards for the new realism were, it’s where Close takes the process from there that is truly astounding. Through subsequent portraits he explores every possible manner—in an amazing variety of media—of transferring and rendering his graphed cells to another surface, as if trying to coax the very molecules of his medium to reveal their secrets of representation. From various drawing and printmaking techniques to grid-sized squares and circles of handmade, grayscale paper, Close continues to alter the variables of his system, deliberately problematizing a process that, once established, is largely mechanical and, indeed, prefigures the pixels of digital photography and printing by decades. Close was ahead of the curve in this regard; what artists in the last few decades have adopted as a powerful tool of automatic image production (digital media), Close made by hand through concentrating on only a handful of images. In one phase, he even abandons implements altogether, using only his fingerprint in stamp pad ink as his mark-maker—the ultimate symbol of individual identity made subservient to the artist’s subversion of portraiture.

Despite the self-portraits’ documentation of inevitable changes in facial hair, clothing and eyeware over the decades, viewers may well tire of Close’s face after a time. The genre of self-portraiture does tend to retain an underlying note of vanitas, but at least two factors mitigate this distracting dimension: First, the curators’ choice of an exhibition of all self-portraits levels the playing field of Close’s work—without drastic changes in the subject depicted, our attention is drawn to the process at work and its strangely compelling results; second, there are some curious developments and accidental effects revealed along the way. One such curiosity is that Close’s maquettes (small-scale mock-ups) for his work have been preserved by collectors, and exhibited here, as works unto themselves. These photographs with masking tape borders and superimposed grids are apparently offered as “proofs,” that we may constantly assess the degree of success in the accompanying drawing, print or painting. They also tend to emphasize the bureaucratic/photographic nature of Close’s “flat-footed” approach: The mug-shot images are captured behind the bars of an alpha-numeric graph in a modern twist on the geometric perfection of the Vitruvian Man. The accidental comes to the fore with one self-portrait maquette in which the upper portion was water damaged, the photographic emulsion washed away as if to remind us that photographs are ephemeral documents of reality, and not reality themselves.

It’s hard to say where Close’s unique process may have led without the biographical upheaval of 1988, when a spinal artery collapse rendered the artist a quadriplegic within a few hours. But, determined to proceed with his well established program, Close continued to paint—first with a brush held in his teeth, then, when he recovered some use of his hands, with a custom brace. For a time, this disability caused Close’s work to become smaller, his “pixels” larger and his application of media more blunt. But this in turn led to another chapter in the incredible evolution of Close’s style: The difficulty of rendering each cell presents a new challenge that results in a matrix of hundreds of abstractions that work together to form a representational whole. The paintings from this post-recuperative period are captivating in the way they make our eyes dance between isolated abstractions and the organic, comprehensive image. A painting in this mode, Self-Portrait (2000-2001), forms a fitting pendant to 1968’s Big Self-Portrait not only in its similarly monumental scale but in its pulsating contrast to the atomized slickness of the earlier watershed canvas.

It’s no wonder that Close eventually took photography from source material for his work to the work itself. There had always been a slippage between his photographic maquettes and the resulting work, with paintings like Big Self-Portrait virtually indistinguishable from the photograph, but for the scale. One of the first photographic processes Close embraced as a direct production tool was the large format Polaroid, because of the immediacy and the exceptional size of the images it produced. This, of course, allowed Close to conflate the process of representation he had so painstakingly fostered, cutting directly from face to photographic portrait. But in true form, Close applies the grid once again, making composite images such as Self-Portrait/Composite/Six Parts, where the edges and inexact alignment of the photographic segments produce a somewhat disjointed whole—sometimes subtle and sometimes jarring in its mad-scientist suturing of the face presented. Some of these composite works are installed with pins, such that the edges are allowed to curl, further drawing attention to the medium as a deceptive mirror.

Perhaps the most curious of Close’s forays into photography is his experimentation with daguerreotypes, an early photographic process known for its delicacy as well as the astounding resolution achieved. But the choice of daguerreotype makes sense when we remember Close’s obsession with the microcosmic aspect of representation. (In this sense, Close’s surname is ironic.) The daguerreotype has been famous since its inception for its seemingly magical quality to capture images in a silvery, supernatural memento mori. The effect is accentuated by the necessit, due to fragility of the emulsion, to display these prints in protective cases; those used on Close’s self-portraits in the exhibition are like tiny black coffins for the hyper-detailed effigies inside. Here, Close has gone to the extreme in his quest for the essence of representation, fixing his face in a medium where no building-blocks are discernible, even under the utmost scrutiny. And for the first time, Close presents a “self-portrait” conveyed not by his face but by his hands, with Hand Diptych II. It is as if he’s broken the mirror-lens’s grip on his gaze and looked down to observe and record the part of his anatomy that has labored so long to deconstruct what the camera can create in the fraction of a second.

Throughout this work, Close is literally exploring the phenomenon of re-presentation like no other artist. A bowl of fruit might have served equally well as subject for this multifaceted, epic experiment, but we come to realize that the human face—and particularly one’s own countenance—is the most highly charged with potential for meaning of any subject. The constant irony is that Close renders the self-portrait virtually powerless in terms of its psychological dimension while he empowers it in terms of its visual thrall magnified through transference. One of the daguerreotype self-portraits serves as a playful finale to this survey of Close’s self-portraiture: Looking very much like a Victorian Saint Nick on summer vacation, he cracks a smile—the ultimate subversion of his own program, infusing more than a hint of character into this long line of shot, scrambled, stoic heads.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n33: Act Small, Think Big: The Micropark Revolution (8/16/06) > Close to Home This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue