Next story: Letters to Artvoice

Face to Face

by Gerald Mead

The late summer can seem like the doldrums for art exhibitions—some galleries even take a well deserved siesta during the month of August—but the inspired exhibitions on view at CEPA Gallery are ample evidence that the art community is alive and well during this sultry season. Combined with the stunning retrospective exhibition of Chuck Close’s self-portraits at the Albright-Knox and a bevy of self-referential works in all media in the Hallwalls Members’ exhibition (hurry, that one closes September 1), we currently have a critical mass of the art of portraiture on view in Buffalo. Those at CEPA are particularly powerful, partnering soldiers in one exhibit with presidents in the other.

Most recently shown at Light Work in Syracuse, Suzanne Opton’s portrait series simply titled Soldier is highly thought-provoking and provocative. Given current US involvement in foreign conflicts, it is a timely body of work and one that will resonate with viewers on varying levels depending on their personal connections with and/or perceptions of the military. The fact that my younger brother is a lieutenant colonel in the US Army who served two tours in the Middle East undoubtedly colored my experience with this exhibition. Conversely, the artist has a son who is old enough to be called into service if there were a draft.

Opton’s subjects for these portraits were all soldiers on temporary leave at Fort Drum in 2005. Having served and returned unwounded from at least 100 days in Iraq or Afghanistan, they were waiting to be redeployed to Iraq or elsewhere. The artist’s intent was seemingly simple and straightforward. She wanted to “look into the face of someone who’d seen something unforgettable.” The label of each portrait identifies the soldier by first name and the number of days that he or she served abroad.

The exhibition consists of a series of 17 black-and-white prints and 12 large-scale color prints. Most of the life-sized, black-and-white prints are of the traditional studio portrait variety—head and shoulder shots. In several of them, however, the soldier’s head is held and cradled by another individual or fellow soldier. These hands around the face and neck seem to represent love, concern and protection—even suggesting a parting embrace before they leave for another tour of duty. This device is sensitively used and not overdone. Consequently the effect is not overly sentimental. Glimpses of wedding bands remind us that many of these subjects have spouses that they will leave at home. The lack of overt facial expressions leaves them open to interpretation and draws the viewer momentarily into their world. How can we comprehend the experience of spending 102, 183 or even 368 days in a war zone?

Ultimately we begin to question how we are affected by staring into their gaze and what we wish we knew, or don’t wish to know, about their experience.

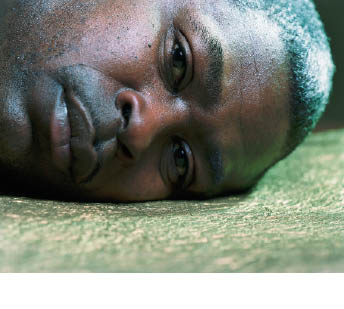

The large-scale color prints, close-cropped portraits of the heads of soldiers lying on their side, are by far the most powerful and moving works in the exhibit. The scale of these works renders the faces much larger than life. Here the experience of gazing into a soldier’s eyes can become unsettling, a feeling somewhat akin to conversing with someone who (for whatever reason) is standing too close to you—referred to in psychology as “invading one’s personal space.”

The position of the head brings up other considerations that affect our response. A human head lying on its side is an unnatural and uncomfortable position. Knowing that these are soldiers, we may deduce that this is a reference to injury or death. In these color prints the expressions seem hauntingly blank. We’re left to fill in the blanks by imagining what the soldiers have seen and what state of mind they are in as they prepare to return to war. That inner silent dialogue that we have with each of the soldiers—a desire to know the unknown—is what makes the work so powerful. Though these prints are very tight shots of the head, the photographer keeps in the frame a tiny sliver of US Army green t-shirt at the neck. It is a subtle and possibly unconscious detail, but it serves to remind us that the subjects are members of the military.

There are many historical precedents for soldier portraiture, some as early as the daguerreotypes in the 1840s, but Opton’s take on the subject is unique and compelling. Her portraits are masterfully lit and composed, precise and elegant. She is an accomplished documentarian who has chosen a highly charged subject and addressed it with aplomb.

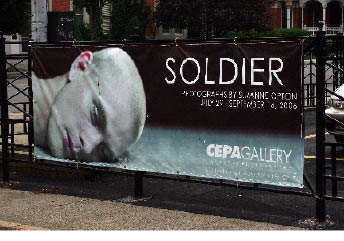

The power of Opton’s portraits is not confined to the gallery walls. Feeling that the images should reach further into the community, CEPA has created large-scale banners from one of the images and canvassed the city, placing them at several well trafficked intersections, such as Delaware and Edward, Chippewa and Pearl, Tupper and Washington and Parkside and Florence. Two of these compelling soldier portraits will also appear in bus shelters throughout the metropolitan Buffalo region courtesy of the NFTA. The artist plans to work with local veterans groups in Western New York to research an extension of her series, photographing mothers of soldiers.

In 2003 photographer and media artist Lara Odell, now a resident of California, was awarded a solo exhibition in CEPA’s Members Exhibition. Now presented in CEPA’s FLUX Gallery, her recent series titled 37 Presidents simultaneously connects with and serves as a counterpoint to the history of presidential portraiture. That history includes everything from the mundane, such as postage stamps, currency and presidential souvenirs, to the monumental, including Mount Rushmore and revered official White House portraits.

Odell’s source material for her series of digital prints clearly falls under the mundane category. She happened upon a set of 1960s-era, small, painted plastic figurines of each American president from Washington to Nixon. In reality, the presidents have ranged in height from just over five feet tall (Madison) to six feet four inches (Lincoln). However, in an odd nod to conformity—more likely a matter of convenience for the designer—all of these plastic presidential figures are the same diminutive two inches high.

These mass-produced, representational collectibles/educational toys became Odell’s “models.” Odell unified the figures in the set by photographing them all in the same fashion—from the knees up, against a gray background—and then installing the square format prints in one continuous timeline that extends the full length of the gallery. The lack of fine detail and crude paint application on the figures becomes even more pronounced since Odell’s prints depict them more than five times their actual size.

Is it a stretch to make an analogy between the physical imperfections and abrasions on the figures and the modern-day media scrutiny that public figures are subjected to? Maybe not. This uniform march of our presidents is a mini-course in period dress from the 1700s to present as well as a test of one’s knowledge of history. (The fact that these toy figures were even made is an interesting reflection on a time when history was fodder for playthings.) No doubt you’ll easily identify Washington, Lincoln, FDR and Kennedy, but does anybody really recall what James Polk and Franklin Pierce look like? Odell’s decision not to identify the portraits by name in any way is a wise one, since it encourages viewer curiosity and inquiry. Part of that exercise is the examination of each figure’s pose and posture to discern their essential characteristics/personality, and perhaps hints of their legacy. For examples, Nixon’s arms and seemingly clenched hands are firmly at his sides, whereas his predecessor Harry Truman is shown with open, outstretched arms. And why does one of our early presidents—a bit of sleuthing informs me that it is James Tyler—have one hand behind his back? An underlying premise here is that we have distinct memories and regard for the men who have held the highest office in our country.

Odell’s recontexualization of the figurines and unifying presentation invite us to appreciate and examine our presidential history and the humanity of the holders of that office. Her “micro to macro” depiction is a highly effective device to aid that examination. The fact that her source material is a mostly forgotten product of the toy industry (the figures were created by Marx Toys, “America’s oldest and most beloved Toy Company”) adds to the appeal.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n35: Face To Face (8/31/06) > Face to Face This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue