Paging Arlo Guthrie

by George Sax

Maybe you could get anything you wanted at Alice’s famous restaurant of yore, but forget about that at Kenny Shopsin’s eponymously named New York eatery, even if the profane, pungently quirky proprietor does claim to offer 900 dishes and items (probably a matter of forgivable hyperbole). Sometimes, you can’t get anything you want at Shopsin’s because Shopsin may refuse to serve you. In I Like Killing Flies, Matt Mahurin’s documentary about Shopsin and his popular joint, one woman, a patron and, evidently, a regular, tells us she has had “the honor of being thrown out. I believe everyone should have it.”

“They have to prove to me that they’re okay to feed,” Shopsin says, one of the numerous salty assertions, apothegms and observations that may or may not be intended for swallowing whole. For one thing, Shopsin doesn’t serve parties of five, only four or less. Not even if they split into parties of two and three, because to Shopsin, they’re still parties of five. It says so right on the sign in the front window. (Sample: “It doesn’t matter if you’re a tackle for the Chicago Bears, you’ll always be a party of five.”)

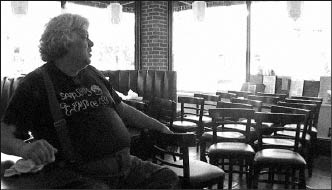

“If you didn’t know the rule, it means you’re not a regular,” Shopsin says dismissively, as he busies himself in his cramped but efficiently run kitchen. He’s been plying his culinary skills and oddball, mildly intimidating, but generally ingratiating and bracing ethos at the same Greenwich Village location for 32 years as the movie begins. His restaurant looks to be little more than a hole-in-the-wall storefront diner, but its meals are inventive and reliably good enough to have attracted a large, sociologically diverse corps of patrons who are willing to pass muster. The resulting mutual loyalty is indicated by the owner’s ethical take: “You treat people who don’t deserve it with respect because you don’t know when someone’s only temporarily undeserving.” It’s obvious that Shopsin regards his work as a calling as well as a business.

From what we can see and hear of it, Shopsin’s fare is a superior and boldly derivative version of short-order cum old-fashioned coffee-shop cuisine. Shopsin is a lot more than an expert fry cook. He’s serving some creatively cobbled-together, internationally influenced cooking, as well as solidly grounded, old-fashioned food. He calls it all “fusion cooking with sexual tension.” A guide someone reads from on camera recommends the place, noting, “The coffee’s good; you have to get it yourself. If you don’t like that, you know what you can do.”

Mahurin seems to have mostly alternately sat around with Shopsin and followed him about with a video camera and mic (which at one point obtrudes into the frame), letting the guy kvetch, comment and aphorize in sound-bite-size utterances, interspersed with the occasional interpolations of others, including the wife and two sons who help him run the restaurant.

The movie, with its in-close, jerky cinematography, doesn’t seem the work of someone who’s a veteran photographer and music-video and feature-film director. Perhaps the lack of discernible technique is a choice in favor of making the subject even more prominent.

Such narrative arc as there is involves the restaurant’s eviction by a new landlord and the difficult challenge of finding a new site in Manhattan’s daunting real estate market. There is an ostensively successful outcome, but one with a concurrent bittersweet development.

Shopsin comes across as a genuine, if modestly situated, genius. It’s hard to imagine him and his establishment outside New York. The cosmopolitan eccentricity of both his personality and his cooking wouldn’t play in a place like Buffalo, for instance. Which is Buffalo’s and most of the rest of the country’s problem.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n36: Three Men in a Room (9/7/06) > Film Reviews > Paging Arlo Guthrie This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue