Pop Tones

by Donny Kutzbach

I recently found myself in a debate about the UK rock scene of the 1980s. I ended up sparring with a guy whose opinion I value but who shocked me when he said that the 1980s acts from the Isles lacked a rock bite of those who’d shaped the previous decades. He made his point asking, “Where were the bands like the Stones, the Beatles, the Who? I guess the ’80s was the price to be paid for such early brilliance…the Decade of Mope.”

Decade of Mope? How dare he. Then I got to thinking about it, and this guy’s rationale was what made me (and so many others, I’m sure) gravitate to something else. Rock needed to change and punk did that. The postpunk bands continued it. We didn’t need to follow the stadium-filling, acid-washed masses defying Bon Jovi and the onslaught of crummy American bands like ’em.

Okay, in fairness, the mope thing might be partly true. English bands like the Cure and Bauhaus traded in that cloud of gloom and a harrowing darkness; it was all thoroughly English. The same, however, could be said of Pink Floyd. You wouldn’t dare call them goth, would you?

The last couple of months have seen some reissues of some key acts and a couple of the most groundbreaking albums of postpunk.

No band was trapped in punk rock’s tidal pool as much as Public Image Ltd. Following the dissolution of the Sex Pistols, John Lydon (né Rotten) hooked up with ex-Clash guitarist Keith Levene and bassist Jah Wobble for a thoroughly experimental, boundary-pushing band that would forever be referred to as PiL. The band chose to follow up their 1978 debut Public Image with something entirely different.

Housed in an unwieldy metal film canister, Lydon and company issued Metal Box as three plain, white, 12-inch records to be played at 45 rpm. (It was put out a year later as a less unwieldy regular-sleeved, 33 rpm double LP set, Second Edition.) Toiling in krautrock and dub, the songs on Metal Box were immersed in the abstract and arty but not so much as to forget the funk. Levene, Wobble and Lydon installed this music with no uncertain dance groove (thanks to the flurry of different drummers playing on it) and it’s what makes the album so important. Songs like “Poptones” and “Swan Lake (Death Disco)” manage bold inventiveness and experimentation while moving with cool and sexy panache. Along with Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, Metal Box ranks as one of the greatest postpunk records. Now, thanks to Runt Distribution, it has been reissued in all of its circular, shiny steel glory as six sides of vinyl in that infamous can with PiL stamped onto it.

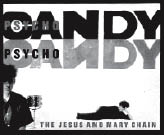

PiL’s dissection/destruction/rebuilding of sound was not lost on Scottish brothers Jim and William Reid, who formed their band the Jesus and Mary Chain 1984. Within a year they issued Psychocandy, a genre-defying, ear-shattering epic of love, alienation and white noise that at once was in awe of Phil Spector’s wall of sound and the Velvet Underground’s raw directness. The difference was the Reids’ take on the wall of sound meant shards of punishing feedback and white-hot, paint-peeling guitar distortion crossed with a detached, black-leather cool. Behind all the cacophony and reverberating there was something else. One listen to these songs revealed pop classicists not hiding behind noise but refiguring rock and roll.

Twenty years on, the power of the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy is undiminished and its latest reissue on Rhino (along with the four Mary Chain albums that followed it: Darklands, Automatic, Honey’s Dead and Stoned & Dethroned) shows it not only to be the jumping off for shoegaze movement that yielded bands like My Bloody Valentine and Ride but also effectively (and noisily) inspired Nirvana, Nine Inch Nails and the Pixies, who went so far in their fandom as to cover JAMC’s “Head On” on their seminal Trompe Le Monde.

The first time I ever saw the Pixies was opening for the Cure. No postpunk band was bigger than the Cure. With smeared lipstick and black haystack mop hair, singer/guitarist Robert Smith is perhaps the patron saint of the broody, dirgey church of English pop. Smith’s Crawley band succeeded like none of their peers, crashing the pop charts on several occasions and filling arenas in America, like a bizzaro flip of the hairspray coin to the aforementioned accursed Bon Jovi.

As Rhino continues the overhaul of the complete Cure back catalog on Elektra, some of their best material is finally getting re-upped. The Top is one of the Cure’s least commercial but thoroughly interesting albums of the band’s career. Smith’s “solo album” Blue Sunshine, recorded as the one off the Glove, shows Smith (along with Siouxsie and the Banshees mate Steve Severin) puppeteering his dark pop through singer Jeanette Landray. (Perhaps the most interesting thing among these reissues is hearing the Blue Sunshine demos with Smith actually singing the songs!) Then there’s The Head On The Door and Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me. Here are arguably the most pop-savvy and pop-perfect records of the band’s career yielding songs like “In Between Days,” “Close to Me,” “Why Can’t I Be You” and “Just Like Heaven.” In less than 10 years, the Cure went from being Buzzcocks copycats crashing the punk party to a pretty keen act that could craft breathtaking pop while never losing their moodiness. And that’s moodiness—don’t ever call it “mopiness.” At least around me.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n36: Three Men in a Room (9/7/06) > Pop Tones This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue