Next story: Zoom-Zoom With Room

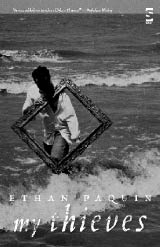

My Thieves: Poems by Ethan Paquin

by Peter Conners

Who is Ethan Paquin? If we are to believe Part VIII of the title poem of his new collection, My Thieves, then, “Ethan Paquin is an aggregate/of sinew and worn things/that wrinkle easily.” This strikes me as true. Throughout the collection, Paquin adds surprising postmodern wrinkles to worn things, including a healthy serving of archaic language. When is the last time you saw the words “sleepe,” “addresseth,” “poesie” and “borne” in a poetry collection published in this centure (I mean, century)?

In many ways, Paquin is a master language upholsterer—refitting these precious, delicate spellings for new use, while retrofitting their allusions for a contemporary audience. But Paquin’s similarities to 17th-century metaphysical poets (named as such by Samuel Johnson) goes beyond his appropriation of their language. Metaphysical poets—John Donne being the most prominent example—stood out in their time for appealing as much to their readers’ intellects as their emotions. In Paquin’s case, this intellectual concern is often directed toward the writing of poetry itself. This is, of course, one of postmodernism’s lasting contributions to the poetry of our time. However, Paquin takes this one step further, focusing his meta lens on what it means to be a poet in today’s culture: to use words toward a spiritual and honestly intellectual purpose in a time when the flexibility of language to tell a story has been stretched to the point of snapping by media, politicians and advertisers.

So how does a young poet reclaim his language? Some strategies which Paquin wields to great effect are the uses of nontraditional punctuation, structure and typography. In his poem “Lax Lax” we encounter long strings of letters—sometimes whole words in a line, sometimes one word stretched out over three lines—running down six different columns across two pages. Is this line-break taken to the extreme, a concrete poem illustrating the minimalism that Paquin addresses in the poem, or something more? At the end of the poem, Paquin refers back to the structure and content of the poem itself: “the viol/ent/est/type./see/the/blank/ness?/I’m/in/it.” In one thin line of text, Paquin swoops down over the metaphysical concerns of this particular poem, poetry itself, the poet inside the poem and the tools—in this case, type—that poets use to communicate.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n14: Polonia on Parade (4/5/07) > Book Reviews > My Thieves: Poems by Ethan Paquin This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue